By David Ross. I offered a little paean to the independent film here, but what would such a paean to the contemporary Hollywood comedy look like? The Hollywood comedy is, if not dead, at least writhing on the floor and gasping for breath and rapidly turning blue. Netflix’s selection of new comedies is a flotilla of cliché-ridden, two-starred dreck, of which a film like You Again (2010) is representative. Kristen Bell, Jamie Lee Curtis, and Sigourney Weaver head a mildly promising cast, but the film is a mire of clichés. Here’s the plot in Netflix-speak:

History – make that high school – may repeat itself when Marni (Kristen Bell) learns that Joanna (Odette Yustman), the mean girl from her past, is set to be her sister-in-law. Before the wedding bells toll, Marni must show her brother that a tiger doesn’t change its stripes. On Marni’s side is her mother (Jamie Lee Curtis), while Joanna’s backed by her wealthy aunt (Sigourney Weaver).

Every character is a deliberate incarnation of cliché: the nerd-turned-LA-public relations-whiz-who’s-still-a-nerd-at-heart, the head cheerleader who sadistically delights in tormenting her social inferiors, the salacious granny who says things like “If you don’t go for him I will” (this an attempt to reverse the eighteenth-century cliché of Mrs. Grundy, never mind that this cliché was killed off decades ago, possibly by Auntie Mame), the eye-rolling, wise-ass younger brother whose sarcastic sallies are affectionately disregarded. And of course the film ends with psychotherapeutic reconciliations and teary hugs. Comedy depends on surprise and sudden anarchic subversion. Cliché is anathema to surprise and the reverse of subversive. Thus a film like You Again is, by definition, dead on arrival.

I’m interested in You Again only as an example of the countless comedies that go quietly to the doom of bored trans-Atlanticists who watch thirty minutes and decide to snooze or fiddle with their iPhones. Movies like this don’t even bother to resist their fate; they may even seek it on the principle that formulaic death-in-life is less culpable than risk.

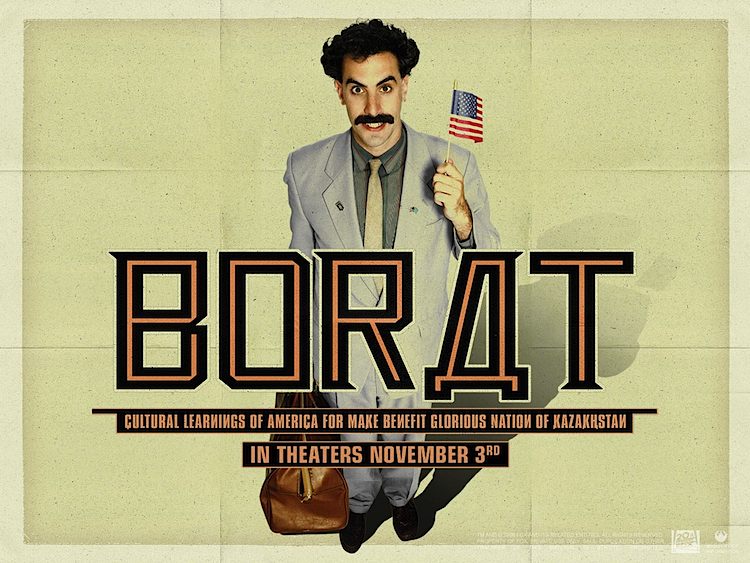

Genuinely funny films like David O. Russell’s Flirting with Disaster (1996), the Coen brothers’ Intolerable Cruelty (2003), Borat (2006), and Greg Mottola’s Superbad (2007) are exceptions that prove the rule. Ben Stiller in Flirting with Disaster reminds us of Ben Stiller in Zoolander, Dodgeball, Envy (don’t even remember this stinker, do you?), Starsky and Hutch, Night at the Museum (1 & 2!), The Marc Pease Experience, and so forth. Jonah Hill in Superbad reminds us of Jonah Hill in calibrated conventionalities like Knocked Up, Saving Sarah Marshall, and Get him to the Greek. Rowan Atkinson in Black Adder – perhaps the funniest turn in all of contemporary comedy – reminds us of Rowan Atkinson in The Lion King, Johnny English, and Mr. Bean’s Holiday.

Genuinely funny films like David O. Russell’s Flirting with Disaster (1996), the Coen brothers’ Intolerable Cruelty (2003), Borat (2006), and Greg Mottola’s Superbad (2007) are exceptions that prove the rule. Ben Stiller in Flirting with Disaster reminds us of Ben Stiller in Zoolander, Dodgeball, Envy (don’t even remember this stinker, do you?), Starsky and Hutch, Night at the Museum (1 & 2!), The Marc Pease Experience, and so forth. Jonah Hill in Superbad reminds us of Jonah Hill in calibrated conventionalities like Knocked Up, Saving Sarah Marshall, and Get him to the Greek. Rowan Atkinson in Black Adder – perhaps the funniest turn in all of contemporary comedy – reminds us of Rowan Atkinson in The Lion King, Johnny English, and Mr. Bean’s Holiday.

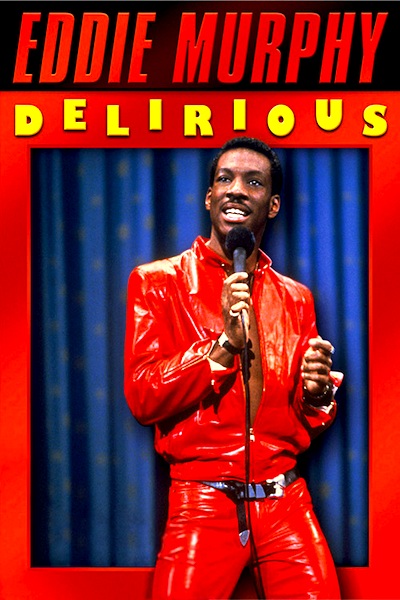

In the last twenty or thirty years, Hollywood has spent billions of dollars on comedies that have produced a few sniggers among thirteen-year-olds, but left this rest of us with a sense of having been gypped and maybe even insulted. It has also serially wasted the talents of generations of not untalented comedians. To those mentioned above, we can add countless others, beginning with Eddie Murphy, a legitimate comic genius (v. Delirious) reduced to whooping it up with barnyard animals. How does this happen?

A comprehensive explanation probably has a few components. There is of course the quest to hedge one’s bets and play it safe, which is part of the innate economics of the modern film industry, in which star vehicles begin $10 or $20 million in the salary hole. There is also the coarsening of the film audience along with the rest of the culture. Verbal high-wire acts like Ball of Fire and His Girl Friday assume audiences conditioned by the mordant witticisms of Mencken and the bright sophistication of Broadway show tunes and the lively bloodsport of cities with numerous daily newspapers. Audiences reared on video games and public school political correctness tend to go glassy-eyed while trying to follow a baseline rally of ironic badinage. Here’s a test: show a young person “Duck Amuck,” the most manic and zanily postmodern of the Loony Tunes. I bet they don’t laugh.

The most basic problem, of course, is the collapse of the writer’s craft, in Hollywood as elsewhere. This goes along with the general coarsening mentioned above, but it has particular impetus and cultural logic worth mentioning. The culture of the sixties was essentially a neo-romantic manifestation, in which the sense of play was replaced by moral earnestness and spiritual aspiration, resulting in certain mythic masterpieces and much searing anti-establishment politics, but also in a scarcity of laughs. In this milieu, writers ceased to think of themselves as wits and began to think of themselves as teachers and point-makers, perhaps even as prophets of a sort. Like all teachers and point-makers, they eventually grew dull with their own lessons and bored with their own sincerity and lost the light, mischievous, self-delighting touch that comedy requires. This point-making impulse is detectable – and ruinous – even in a neo-screwball comedy like You Again.

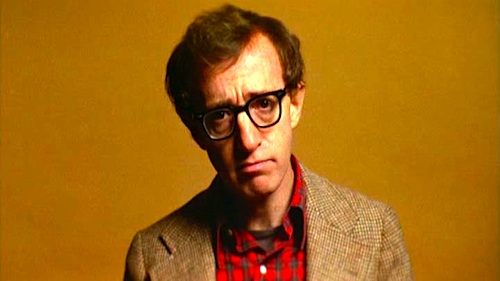

Woody Allen, who kept up the old Borscht-belt traditions to good effect at least through the 1980s, instinctively understood all of this, which partially explains his rearguard battle against the ethos of the sixties (the great implicit theme of Annie Hall). Woody disdained the pot-smoking, hard left politics, and New Age mistiness, but more basically mistrusted the insistence that life should take the form of a cause, whether spiritual, moral, political, or personal. Causes are not funny; people who devote themselves to causes are not funny (unless they are being satirized, as in Dickens). Having lost this battle against the Jane Fondas and Robert Redfords of his own generation, Woody seems to have grown discouraged and remote, recycling his old tropes in bitterness and frustration.

Romanticism and comedy are intrinsically inimical and always have been; there is no such thing as romantic comedy in the Wertherian or Wordsworthian sense of the adjective, though certain romantics (like Keats and Byron) can be funny when they temporarily abandon the romantic barricades. If we are to recover the art of comedy, we must, to extend my historical analogy, recover a spirit of Augustan wit. Like Joel McCrea in Sullivan’s Travels, we must realize that comedy is for laughs while society fends for itself.

See related discussions here and here.

Posted on September 16th, 2011 at 11:10am.

Here’s a test: show a young person “Duck Amuck,” the most manic and zanily postmodern of the Loony Tunes. I bet they don’t laugh.

Of course not, the cartoon is about Bugs being mean to Daffy. We all know that there’s nothing funny about that!

So, boiling down your conclusion here, you’re saying that humor is the canary in the totalitarian coal mine. And the canary is looking kinda sick.