TNT, Tuesdays at 10 p.m.

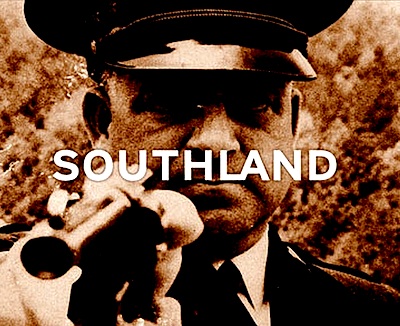

By Patricia Ducey. There’s a spot on L.A.’s 101 freeway near Vignes Street where, if you look up at the right time of day, you can see the silhouettes of a half dozen or so helicopters–the LAPD air support unit–on the roof of their headquarters on Ramirez Street. It’s an awe-inspiring, fearsome sight. I get the same vibe at Southland’s opening credit roll. A series of sepia-toned photos of local crime scenes scrolls by, starting with the muzzle of a very large gun aimed straight at you, buddy, by a grinning 1960s-era L.A. cop. Against the slideshow are the martial tones of Martin Davich’s theme music of thumping bass and staccato drumbeats, that telegraphs a clear message: bad guys beware. This is Los Angeles, the mythic Los Angeles of TNT’s ever improving and innovative Southland.

Yet, as unapologetically fierce as the opening sequence may be, Southland is more about the power of ideas than power for its own sake. The body count is remarkably low, and the cops spend as much time talking to their citizens as busting them. In contrast to the patricians of Law & Order who fought the forces of chaos in the rarified air of law courts, or the wonky CSI techs in sterile labs, Southland‘s cops attack cases and problems from the bottom up, at street level. These L.A. cops aim to restore character, as well as order, to the beat. Call it nation building in L.A., if you will. And thanks to rich, layered writing, non-PC characters and fresh production style, we come to believe – like these cops – that they might just pull it off.

John Wells of ER tapped NYPD Blues veteran Ann Biderman to create the show and she rode along with the LAPD for several months to immerse herself in its culture. The resulting writing is so rich in detail that even the smallest scene is not wasted; each detail adds heft to the character or storyline. Her characters have mastered the nuances of every gang, every drug network, and every neighborhood from the West Side to Boyle Heights. As the detectives search an alley for evidence, for instance, a drug addict ambles by, listing from left to right in precarious fashion. “Don’t worry,” the veteran replies matter-of-factly to the rookie’s alarm, “they never fall down.” And he doesn’t, much to the surprise of the rookie. The officers eat lunch at real fast food joints or taco stands and chat endlessly about where to eat, to alleviate the monotony of an uneventful patrol. They solve a business dispute between a drug dealer and his buyer and defend a transvestite business owner from local bullies. They break up at least one marital fight per episode. They crack jokes—about each other, about the crazies they meet. And it’s all compelling—we are never sure what is going to happen next.

Southland’s characters defy neat types, as well. The centerpiece of this ensemble is the partnership between rookie Ben Sherman and his training officer, John Cooper, who spends the first couple of episodes training—hazing, really—the rookie from Beverly Hills. But Ben takes it, eventually winning Coop’s respect when he expertly guns down a gangbanger, saving fellow officer Dewey’s life. “Where did you learn to shoot like that,” they exclaim. “Beverly Hills Gun Club,” he coolly responds. And as the series progresses, Ben’s story unfolds. He is not just a rich kid engaging in cop tourism; his own family was terrorized by a criminal client of his criminal defense lawyer father. And Cooper is not the chubby-cheeked bully out to vent his angst on the mean streets, as he first appeared.

Now we are in Season 4 and Coop has overcome an addiction to pain pills that started with treatment for his aching back. He finally states that yes, he is gay, trying to calm a gay teen who has been viciously bullied. Ben registers no surprise, but at first we are not sure if this is just another story he tells to calm down a distraught victim. Thinking back, we realize of course that he’s gay but Southland has rolled out the story of his sexual identity in gradual hints, as they did with other characters, with no exploitation.

Southland pokes fun at overused or politically correct TV police tropes, as well; they even call Ben “Tori Spelling.” They tell nice, sweet stories to victims to comfort them—Detective Lydia Adam’s partner gets almost teary-eyed at one until she tells him that she just made it up. In another episode, a man is stabbed to death at a convenience market; the victim happens to be the witness whose testimony helped send man to prison for life. That man has just been released thanks to new DNA evidence, but the new partner resists Lydia’s notion that he is the killer. After all he’s suffered! After she doggedly interviews him and gets a search warrant she recovers bloody clothes and the murder weapon in the recently freed man’s house. Her new partner is stunned. “I’m not surprised,” she shrugs. More reversals of the trite include a watch commander opening roll call with the sardonic announcement that crime has gone up dramatically now that the courts have released so many prisoners. In another, a hipster in a Smart Car is made to look the fool against Cooper’s cool. Southland‘s stories seem real and original, against the grain of the usual police drama pieties.

But it’s Officer Sammy Bryant’s character that illustrates the “message” (if any) this LAPD is sending. Sammy is the voice that exhorts the people of L.A. to step up and take back their city from the thugs. As fearless and aggressive as he is, he knows that the police can’t keep the peace alone. In Season 1, he urges three teenage girls to testify in a gang murder case. Sweet naïve Janila, in the throes of LAPD hero worship, agrees – if they promise to get her into the Explorers. An irate citizen tells Sammy he is filing a complaint against him for insensitivity at the scene of a crime; Sammy shouts back that he ought to think about helping the police if he wants peace on his street. That stops the complainant short, as if he had never considered the idea. And so the citizen testifies. In the latest episode, though, Sammy may have gone too far: an anguished father curses and punches Sammy in the courthouse hall. Sammy had convinced his son to testify against a gang and the gang killed him. It will be interesting to see where Sammy’s character goes; up until now, his informants have escaped retaliation.

Despite the murder and mayhem, Southland’s L.A. is broken but unbowed. There’s something essentially noble and optimistic that the show communicates. One thinks of Sammy’s aggressive, passionate jeremiads about stepping up, or the constant jokes and pranks to leaven the deadly tension, or Cooper’s masterful techniques to calm domestic fights. These cops are parents in a family of a million children who have lost their way – raised by the wolves of permissiveness and family breakdown – and they do all they can to stand these citizens up and point them in the right direction.

Every series has an arc, and when the arc plays out, the series loses steam. Yet Southland is still in its ascendancy with many stories yet to be revealed. I hope we get to see Janila taking the LAPD cadet oath, which starts with the pledge: “I do solemnly declare upon my honor. . .” For all her naïveté, this call to honor – embodied by Sammy and his comrades – may yet save her from the cheap thrills of the streets. I for one will be watching.

Posted on February 29th, 2012 at 11:00am.