By Joe Bendel. Boris Pasternak’s epic novel Doctor Zhivago was banned, denounced, and was a major factor leading to the Nobel Prize for Literature he was forced to decline. It was also a love story. Unfortunately, the woman who inspired Pasternak faced the full force of the Communist Party’s wrath, to an even greater extent than her more famous lover. Their romance and its legacy also inspired Scott C. Sickles’ play Lightning from Heaven, which officially opened this weekend at the Main Stage Theater in New York.

Set in various cells in the Lubyanka, Lightning is told in flashbacks during Olga Ivinskaya’s many KGB interrogation (torture) sessions. Sadly, she is no stranger to the place. A literary editor by profession, Ivinskaya had more in common with Pasternak than his wife Zinaida. However, as the daughter of a moderately high ranking military officer, Madame Pasternak was able to protect her husband when he publicly spoke out against Stalin.

Of course, the publication of Zhivago was another matter entirely. Zinaida is quite certain she is not Lara. After all, the two fictional lovers never married. Nor is the Party pleased with Pasternak’s portrayal of the Revolution and the subsequent purges, so they target his greatest vulnerability: his mistress-muse Ivinskaya. In order to discredit the late Pasternak and his masterpiece, Vladilen Alexanochkin, the “good cop” KGB agent, engages in a cat-and-mouse game with the sleep-deprived Ivinskaya. Either she will renounce Pasternak and Zhivago, or she will proclaim herself the illicit inspiration for Lara.

In a way, Lightning is like the historical forebear of the dystopian television show The Prisoner, with the question “are you Lara” replacing “why did you resign,” except it is very definitely based on fact. Sickles alters a detail here and there for dramatic purposes, but he is more faithful to history than David Lean’s great film was to Pasternak’s source novel. It is a smart, deeply literate play, driven by the conflict between individual artistic integrity and the collectivist state. Perhaps most touching are the scenes deliberately echoing Zhivago in which Pasternak and Ivinskaya find beauty in the increasingly drab, dehumanized Soviet world about them.

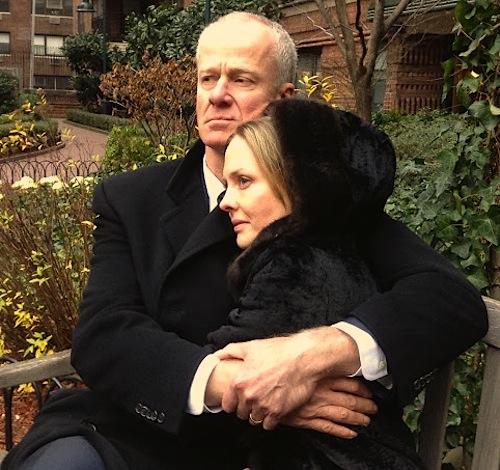

Jed Dickson resembles the Robert Frost-ish Pasternak that appeared on Time Magazine enough to look credible in the part. More importantly, he really expresses Pasternak’s poetic sensibilities. As a private citizen, Pasternak made some problematic choices, but Dickson makes them understandable, beyond the self-centeredness of the creative class (though there is that as well).

Likewise, Kari Swenson Riely is more than a mere victim of the Communist thought police, although she is certainly convincing enduring the KGB’s physical and emotional torments. She develops a comfortable romantic chemistry with Dickson’s Pasternak that is quite moving in an almost chaste way. Yet, when her character stands on principles, she makes it feel genuine and profound, rather than didactic (like, say, a character from Soviet propaganda). It is also important to note the work of Mick Bleyer as Alexanochkin, who keeps the audience consistently off-balance in satisfyingly ambiguous ways.

Perhaps the only historical figure getting short-changed in Lightning is Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, who ruptured his relationship with the Italian Communist Party by publishing Zhivago. He comes across a bit caricatured here, but that is a trifling complaint. Lightning is big idea production, rendered in intimately personal terms. It also boasts an admirably professional cast that continued on like troopers even when a freak accident in the audience forced an unusually long intermission Friday night. Highly recommended for fans of historical drama or Zhivago in any of its incarnations, the Workshop Theater Company’s production of Lightning from Heaven runs through March 9th at the Main Stage Theater on 36th Street.

Posted on February 18th, 2013 at 2:44pm.