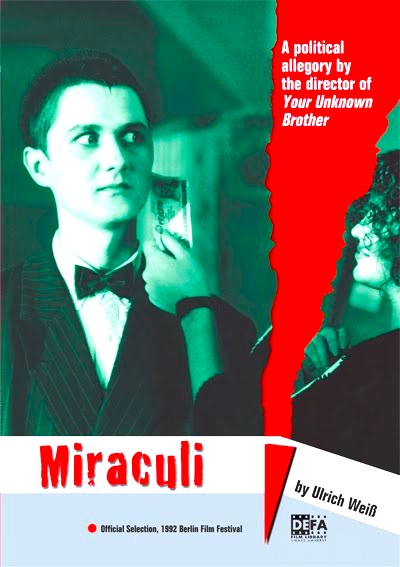

By Joe Bendel. Filmmakers working behind the Iron Curtain had a natural affinity for the absurd and the surreal. Given their experiences under Communism, they could easily relate to such Kafkaesque cinemascapes. It also behooved them to keep their social critiques obscured by layers of allegory and symbolism. A passion project only made possible by the fall of the Berlin Wall (or the epochal “Wende”), Ulrich Weiß’s Miraculi represents the culmination of such cinematic strategies. Finally produced in 1991, Miraculi screens next week as part of Wende Flicks: Last Films from East Germany, a retrospective of the East German DEFA studio’s final years (1990-1994), presented at Anthology Film Archives in conjunction with the Goethe-Institut New York.

By Joe Bendel. Filmmakers working behind the Iron Curtain had a natural affinity for the absurd and the surreal. Given their experiences under Communism, they could easily relate to such Kafkaesque cinemascapes. It also behooved them to keep their social critiques obscured by layers of allegory and symbolism. A passion project only made possible by the fall of the Berlin Wall (or the epochal “Wende”), Ulrich Weiß’s Miraculi represents the culmination of such cinematic strategies. Finally produced in 1991, Miraculi screens next week as part of Wende Flicks: Last Films from East Germany, a retrospective of the East German DEFA studio’s final years (1990-1994), presented at Anthology Film Archives in conjunction with the Goethe-Institut New York.

In the Czech Republic, one of the few annoying holdovers from the Communist era are the plain clothes transit inspectors looking to fine riders who cannot produce their appropriately punched tickets. Evidently East Germany had these transit narcs as well. Through a series of chance circumstances, Sebastian Mueller, a mild mannered juvenile delinquent, joins the ranks of the volunteer transit inspectors. In truth, he is not very good at his duties, but he takes them very seriously, alienating his father, who labels him a traitor to the workers.

Episodic and trippy, Mueller’s story defies pat description. In a strange way, Weiß invests Mueller’s reviled voluntarism with strange and cosmic dimensions. Yet, one can easily glean the power dynamics at work. As one character explains, stiffing the tram is truly the only safe method of rebellion available to her, so who cares if she is caught.

Miraculi’s dense layers of meaning are probably only fully grasped by those who experienced the oppressive drabness of the GDR. That being said, there are plenty of signifiers astute westerners should be able to catch. Indeed, the significance of an abnormal psychology lecture delivered to Mueller and his fellow inspectors is hard to miss, if viewers have any familiarity with the Soviet bloc’s record of institutionalized psychiatric abuse.

Undeniably both subversive and demanding, there is no possible way Miraculi could have been produced under the Soviet-dominated GDR regime. It is a world away from Soviet Realism, even though it scrupulously captures the depressed grunginess of industrialized East Germany. It is a rich, challenging work, recommended to viewers who do not have to “get” everything they see to appreciate a film. It screens this coming Monday (11/1) at Anthology Film Archives as part of the remarkable Wende Flicks series. Truly a cinematic event, many of the Wende selections have never been subtitled or shown outside of Germany, until now. Yet films like Miraculi are both historically important and fascinating in their own right. The Wende Flicks series runs in New York from November 1st through the 3rd.

Posted on October 29th, 2010 at 10:58am.

One thought on “The Last Days of East Germany: Miraculi”

Comments are closed.