By David Ross. Morgan Neville’s The Cool School (2008) is a propulsive, loose-lipped documentary about the birth of an indigenous modern art movement in Los Angeles. It tells the story of painters, ceramicists, and assemblage artists whose hub was Walter Hopps and Irving Blum’s Ferus Gallery at 736a N. La Cienega.

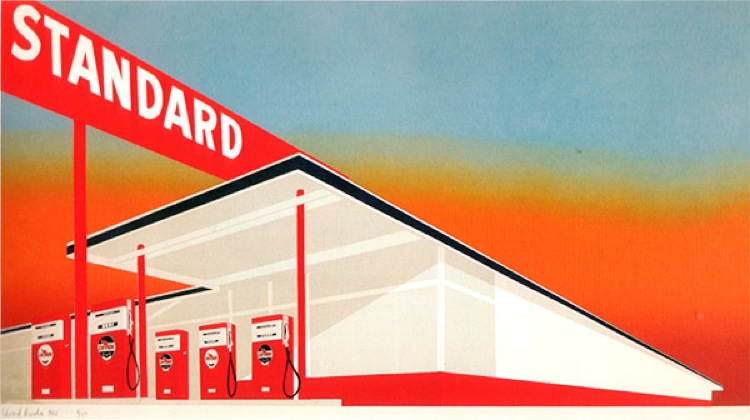

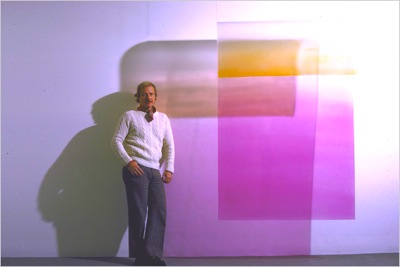

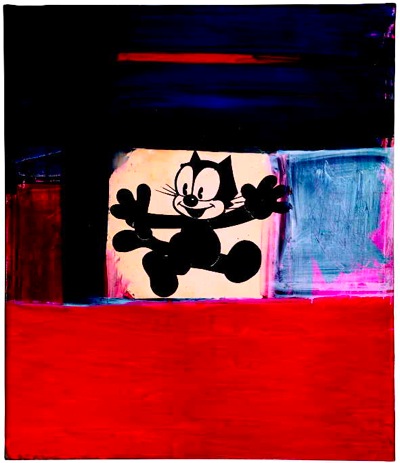

These artists – John Altoon, Larry Bell, Billy Al Bengston, Wallace Berman, Robert Irwin, Craig Kauffman, Ed Kienholz, Ed Moses, and Ken Price – may be unknown to the uninitiated, but Frank Gehry and Ed Ruscha, who moved at the periphery of the group, give the idea. Between the mid-1950s and mid-1960s, these artists led the West Coast transition from the astringency of abstract expressionism to the affectless exclamation of pop and postmodern art, and created from scratch an aesthetic and cultural posture to rival the pomp and self-importance of New York. Their inspirations were local and various: the custom car culture, the surf culture, urban detritus, plastic, glass, signage, the bright sharp aspect of the sunshine and the sand and water, the Pacific light itself. The prevailing spirit was macho, competitive, and hard-living in the Pollock vein, with women present “to service the men” and suffering the usual collateral damage. By the late-1960s, the gallery was hawking the work of New Yorkers like Lichtenstein, Johns, Stella, and Warhol, and the local scene broke up amid long repressed mutual annoyance. Hopps sold out to Blum and Blum moved New York, while the Ferus artists went on to early deaths and/or a degree of fame.

The Cool School artists played out “all of the Los Angeles prejudices,” says Shirley Neilsen Blum, a PhD. in art history who left Hopps to marry Blum.

“They were very involved with the beach and with the surf and with the road and with automobile and with the girls and with the local tavern [Barney’s Beanery]. That’s what they did. They had a lot of spare time. But the studio was a very different place. When they got into the studio, they were alone. And they were all born with the legacy of modernism. In other words you didn’t look at the external world for your subject. The subject came from you … Los Angeles is the city of light and air and reflection and scintillation of surface. They began to play with qualities of perception. Instead of what the impressionists tried to do, which was to see the effect of color on light, light itself became a palpable experience of the object itself.”

The Cool School is interested in social history rather than aesthetic analysis and doesn’t have much to say about the art itself. I would have preferred more lingering reflection on the images and somewhat less gossip and reminiscence. Postmodern art of the surface – superficiality in the literal sense – is the kind of thing I’m inclined to beat with a stick, but I have a hard time mustering my usual ire. While Warhol and Lichtenstein trafficked in crowd-pleasing irony, the artists of the Cool School were at least emotionally sincere, and their emphasis was for the most part aesthetic: they were interested less in social and political commentary than in image, reflecting their origins in abstract expressionism. None of this art seems to me particularly profound, but I can’t say that it’s entirely wrongheaded. Ruscha, the shrewdest and most ingenious artist to emerge from the cool school milieu, largely traffics in ironic conceptual puzzles, but even in his case there’s a redeeming subtlety and sense of humor and refinement of execution that distinguishes him from Warhol. He reminds me, in fact, of Saul Steinberg, another ingenious visualizer of what words mean and a particular hero of mine.

Ignoring its merely sidelong glance at the art, The Cool School is impeccable as documentary craft. Nearly all of the key figures – happily, an unguarded bunch – contribute their recollections and grind their axes, and the film pops with color and sound: vintage footage on the one-hand and a sublime soundtrack of jazz, surf music, and punk on the other. Whatever one thinks of the art – and there’s plenty of reason to be skeptical – nobody is likely to fall asleep.

The film complains that the L.A. art scene was co-opted by glamor-seeking know-nothings from the moneyed world of film. Ironically, then, it taps Jeff Bridges as narrator and indulges Dennis Hopper and Dean Stockwell as a spacey, possibly stoned chorus. Hopper was a major collector of contemporary art, as we all know, but all the same I would have preferred less from posturing actors and more from historians in a position to assess the Cool School and give a larger sense of what it was up to. What’s lacking is any sense of responsible external opinion.

Ruscha, by the way, is making his entire catalogue raisonné available online. As far as I know, this is an unprecedented experiment in public access and self-canonization. See here.

For more Libertas coverage of fine art, see here, here, here, and here.

Posted on October 10th, 2010 at 11:08am.

I clicked over to Ruscha’s site. Not quite as accessible (or “ironic” I guess) as Warhol.

See: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=otPkk1sUFkI

But keep the articles coming David. How about something on post revolutionary Russian abstract poster art? An art style performed under the constraints of being creative, abstract and pretty accessible to intellectuals and the masses without irony.

Either that or you’re going to have to educate the pallets of us art yahoo/engineer types.