By David Ross. David Mamet is our leading playwright as well as an incisive, cerebral film director. He made a splashy conversion to conservatism in 2008, publishing a hoot of an essay called “Why I am No Longer a Brain Dead Liberal” in The Village Voice.

I was pleased but not surprised. All artists of real aspiration must eventually come to terms with conservatism, great art being rooted in the same values and perspectives that conservatism is rooted in – rooted in the assumption, for example, that human beings are more than automata of history, accidents of chemistry, points on a graph, sheep in need of a governmental shepherd.

In the latest issue of Commentary, Terry Teachout, the dean of conservative cultural critics, ponders the impetus and meaning of Mamet’s conversion (for subscribers only, unfortunately).

He traces the crux of the matter to a passage in “Why I Am No Longer a Brain-Dead Liberal”:

I do not think that people are basically good at heart; indeed, that view of human nature has both prompted and informed my writing for the last 40 years. I think that people, in circumstances of stress, can behave like swine, and that this, indeed, is not only a fit subject, but the only subject, of drama.

Teachout comments:

The only unexpected thing about this conclusion is that it took the author of American Buffalo (1975), Glengarry Glen Ross (1984), and Speed-the-Plow (1988) so long to reach it. In these hard-headed plays, which established him as a major voice in American theater, Mamet respectively portrays small-time crooks, unethical real-estate agents, and ambitious Hollywood executives as engaged in identically savage battles for power over one another. His foul-mouthed characters behave like scorpions in a bottle, determined to sting or be stung. They have no past or future, only the unremittingly bleak present, though they somehow manage to entertain us – if that is the word – because of the manic energy with which they do their frenzied dances of death.

The battles in which Mamet’s characters are engaged, as one of them remarks in American Buffalo, the most archetypical (and artful) of his portraits of American life, are zero-sum games in which only one player can win: “It’s kickass or kissass, Don, and I’d be lying if I told you any different.” When these plays were new, this caused them to be read by liberal critics as indictments of the American dream in all its hideous falseness. But the plays themselves are not nearly so explicit. Even as a liberal, Mamet spoke of them not as prescriptive but descriptive:

“Economic life in America is a lottery. Everyone’s got an equal chance, but only one guy is going to get to the top. The more I have the less you have. So one can only succeed at the cost of the failure of another, which is what a lot of my plays American Buffalo and Glengarry Glen Ross are about.”

Therein lies part of the strength of Mamet’s major plays: they present human behavior rather than trying to explain it. None of the characters is obviously sympathetic, nor do any of them step forward at evening’s end to reassure uneasy audiences that they are seeing man at his worst and that a well-regulated society has the power to lead him in the paths of righteousness. Instead, Mamet portrays human life as a Hobbesian war of all against all, leaving it to the viewer to draw his own conclusions about the ultimate meaning of the struggles for dominance that he witnesses on stage. The only difference between Mamet then and Mamet now is that he has decided that government intervention can do little or nothing to ameliorate the effects of these struggles, and that men do better to work out their differences through the operation of free markets.

As a pessimist of human of nature (‘No, we can’t! would seem to be the operative slogan) with a strong libertarian bent, Mamet profoundly flouts the table manners of the Times-reading Upper West Side. Compounding his offense, as Teachout notes, Mamet is an “unabashedly Zionist Jew.” Teachout quotes a splendid little paean to Israel from a 2002 essay that appeared in the Forward:

Here, in Israel, are actual Jews, fighting for their country, against both terror and misthought public opinion, as well as disgracefully biased and, indeed, fraudulent reporting. Here are people courageously going about their lives, in that which, sad to say, were it not a Jewish state, would, in its steadfastness, in its reserve, in its courage, rightly be the pride of the Western world.

Teachout theorizes that Mamet’s conservative turn is at least in part a reaction against the liberal incapacity or unwillingness to grasp the Hobbesian dynamics of the Middle East and the second Holocaust that waits in the wings. Teachout asks, “Might this lack of realism on the part of his fellow liberals have caused him to feel that his own liberal politics were equally unreal by comparison with the cold-eyed disillusion of his plays, and that the plays were thus truer to life than his political opinions?”

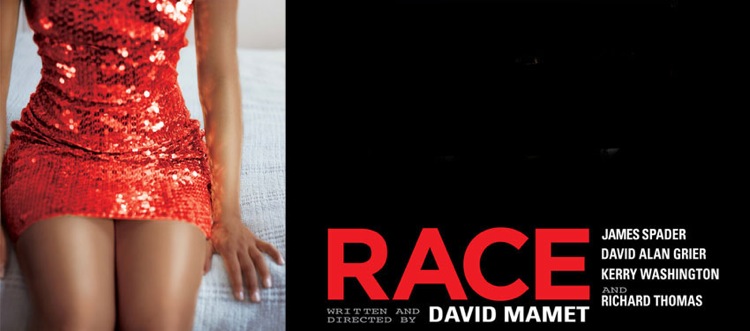

Writing in City Journal, Harry Stein further comments on the Mamet affair and, like Teachout, finds little enough to like in Mamet’s first post-conversion play, Race, which opened on Broadway in December.

During the early 1990s, incidentally, Mr. Apuzzo and I had lunch with Teachout at a function for collegiate newspaper editors (we were editing The Yale Free Press in those days). I remember Teachout expiatiating on Whittaker Chambers, whose journalism he was then editing. Neither of us knew a thing about Chambers, if I am not mistaken, but we have since become devotees of Chambers’ memoir Witness, which is surely one of the twentieth century’s most underappreciated literary masterpieces. You can see Teachout’s hyper-erudite blog here.

Those unfamiliar with Commentary and City Journal should peruse their on-line offerings and consider subscribing. These are the two indispensible conservative periodicals. In addition to the piece by Teachout, the latest issue of Commentary features a valuable article on the translation of Russian literature, which I highly recommend to all readers of Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, and Gogol.

Posted on July 6th, 2010 at 10:05am.

Another thoughtful piece, David. However, I have to disagree that conservatism at its core has this sort of Hobbesian, dog-eat-dog view of the world. I would certainly agree that we have a more clear-eyed view of the world, and we don’t persistently believe the whopping lies that the left does in the face of all contrary evidence (“Communism is great! It’s just never really been tried anywhere!”), but we also believe that people are fundamentally good. We couldn’t believe in freedom otherwise. After all, to believe that individual freedom works is to believe that people will behave in a fundamentally good manner if they have that freedom.

David – this is an interesting and well written piece by you, as always. But I have to quibble with the contradictions in Mamet’s own views. How does he resolve having this “realistic” and “unidealistic” view of humanity, and yet still still support Israel for obviously idealistic reasons? I completely agree with his moral and ethical reasons for supporting Israel, but they don’t seem to go with the rest of his worldview. According to the rest of his worldview, Israel should be left to fight it out on its own, and if they don’t survive it’s just the way of the world that the stronger (the Arab nations around it) win.

I really disagree with this whole idea that conservatism means that if one person wins, another person loses (maybe some conservatives who are more cynical believe this and are just out to grab whatever they can from life, but not me). That’s not the kind of optimistic, Reagan-style conservatism I was raised with. And it certainly doesn’t work when you apply it to Israel.

H. Arundel and Brightstar express some of my own reservations. I too am unsure that the Hobbesian vision is conservative in itself, though I do think that conservative governance is responsive to certain Hobbesian assumptions (i.e., conservatives reject overweening government power because they do not trust their fellow human beings to wield this power responsibly and morally). Nor is the Hobbesian vision that kind of conservatism that underpins the greatest art, But then, David Mamet is not the what I would call a truly great artist; he is merely an interesting and provocative artist. We will have to keep our eye on Mr. Mamet.

I admire Mr. Mamet as a playwrite-I am a littly iffy on him as a self styled philosopher of conservatism. In the dog-eat-dog world he envisions playwrites would have little place, as would the Jewish people.

The funny part of his recent conversion is the swiftness with which conservatives abandoned him as soon as his recent play came out. How completely typical.

I’m no economist, but I don’t agree that a conservative view would render economics a zero-sum game. I’d say the economic success of one person provides more opportunity for others. It’s a rising tide that floats all boats.