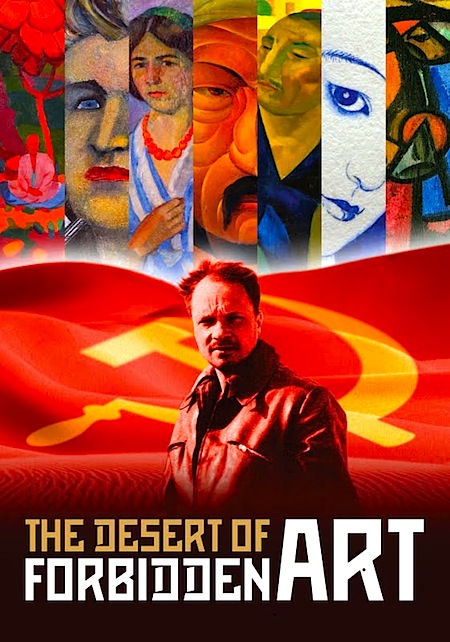

By Joe Bendel. Nearly any art the Soviets would suppress, Igor Savitsky collected—using their money. In a remote corner of Central Asia, Savitsky built the Nukus Museum to house an extraordinary collection of Soviet modernist and Uzbekistani folk art. This unlikely institution and its visionary founder are introduced to the world at-large in Amanda Pope and Tchavdar Georgiev’s fascinating documentary, The Desert of Forbidden Art, which opens today in New York and next week in Los Angeles.

Frankly, as the son of aristocratic stock, Savitsky was fortunate simply to be living in relative liberty during the Stalinist era. After being rudely disabused of his own artistic ambitions, Savitsky returned to the scene of his happiest times, the remote Uzbekistani autonomous republic of Karakalpakstan, where he had served as a sketch artist on an archaeological dig. Savitsky soon began collecting the local folk art considered verboten under Stalinism. However, his greatest acquisitions were the explicitly banned work of Soviet avant-garde artists who had come to Uzbekistan in the 1920’s and 1930’s to avoid the secret police’s prying eyes.

Frankly, as the son of aristocratic stock, Savitsky was fortunate simply to be living in relative liberty during the Stalinist era. After being rudely disabused of his own artistic ambitions, Savitsky returned to the scene of his happiest times, the remote Uzbekistani autonomous republic of Karakalpakstan, where he had served as a sketch artist on an archaeological dig. Savitsky soon began collecting the local folk art considered verboten under Stalinism. However, his greatest acquisitions were the explicitly banned work of Soviet avant-garde artists who had come to Uzbekistan in the 1920’s and 1930’s to avoid the secret police’s prying eyes.

Figures like Alexander Volkov and Alexander Nikolaev synthesized modernism and the exotic Central Asian art into something new and unique to the region. Clearly not working within the Soviet Realism style dictated by the state, their art was quickly banned. Many, like Mikhail Kurzin, were interrogated and even imprisoned. Yet somehow Savitsky managed to convince the Karakalpak party boss to fund his proposed museum (which he did through embezzlement).

While Savitsky’s subversive institution might sound like just another ironic episode of Cold War history, the quality, diversity, and volume of art he collected there is absolutely staggering. Pope and Georgiev choose some genuinely striking highlights to spotlight throughout Desert, but they could only scratch the surface of the 40,000 some works he amassed. However, an estimated 97% percent of the Savitsky Collection is in dire need of restoration.

Not just a remarkable history lesson (though it is surely that), Desert is also a call to action, urging viewers to support the museum. The staff, though passionate, is woefully underpaid, and the building’s environmental controls are essentially non-existent. The Islamist specter also looms over the Nukus Museum. Though not yet directly threatened by Taliban-style militias, Uzbekistan is a Muslim country that shares a border with Afghanistan. Indeed, the Nukus curator is all too aware of the fate of the Bamiyan Buddhas.

Truly, Desert is a revelation several times over. A genuine cultural hero, Savitsky and a handful of highly placed allies saved a treasure trove of exceptional paintings and graphics. Pope and Georgiev tell his story beautifully, featuring work after work of power and originality evident even to the untrained eye, as well as the smoothly polished voice of Sir Ben Kingsley, which well serves Savitsky’s words. Perfectly ending on a note of gentle irony, it is hard to imagine a more insightful or informative documentary will be released this year. Highly recommended for all audiences (and to art lovers in particular), Desert opens today (3/11) in New York at the Cinema Village and next week (3/18) at the Laemmle Music Hall 3 in Los Angeles.

Posted on March 11th, 2011 at 9:21am.

Joe – thanks for all you do to bring documentaries like this to the public eye. I would never have known about this film otherwise. This sounds like an amazing museum, and I wish them the very best in saving these artworks. With all the money flowing through Russia right now, you would think some billionaire oligarch would fund this museum and save these important works.