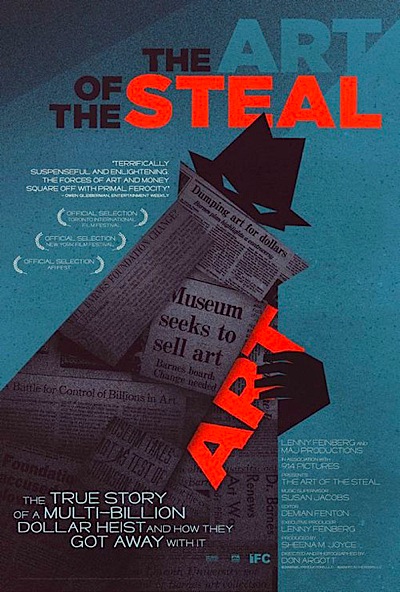

By Joe Bendel. Americans expect their property rights to be respected, even posthumously. However, those rights evidently do not apply to when the property in question is especially valuable. At least that seems to be the case in Pennsylvania, where the state government, the city of Philadelphia, and a group of powerful non-profit foundations have in effect legally plundered the priceless Barnes Collection according to Don Argott’s eye-opening documentary, The Art of the Steal, now available on DVD.

Steal opens with the unseemly yet so appropriate video of former Mayor John Street’s news conference, in which he overflows with glee at the prospect of finally getting the Barnes in Philadelphia. All that is missing is a football for Street to spike before doing an end-zone dance. However, this display is problematic on multiple levels.

Albert C. Barnes hated Philadelphia. The self-made entrepreneur and Roosevelt Democrat amassed probably the greatest private collection of impressionist and early modern art. Yet, when he unveiled his collection in the City of Brotherly Love, it was panned by the local press and mocked by the chattering classes. Eventually, Philadelphia realized what they had missed, but it was too late. Barnes had established his Foundation in exurban Lower Merion, where career-defining Renoirs, Cézannes, Matisses, Picassos, and Degases were integrated into a progressive art school, with only limited opportunities for public viewing.

Albert C. Barnes hated Philadelphia. The self-made entrepreneur and Roosevelt Democrat amassed probably the greatest private collection of impressionist and early modern art. Yet, when he unveiled his collection in the City of Brotherly Love, it was panned by the local press and mocked by the chattering classes. Eventually, Philadelphia realized what they had missed, but it was too late. Barnes had established his Foundation in exurban Lower Merion, where career-defining Renoirs, Cézannes, Matisses, Picassos, and Degases were integrated into a progressive art school, with only limited opportunities for public viewing.

When the childless Barnes passed away, the terms of his will were explicitly designed to keep his collection intact and out of the grasping hands of Philadelphia and its despised Art Institute. However, as the original trustees passed away, control of the Barnes Foundation eventually fell to Lincoln University, a traditionally African American school safely outside the Pennsylvania establishment in Barnes’s day that became state affiliated in 1972. As Argott makes crystal clear, from that point on, Barnes’s intentions no longer governed the Foundation that still bears his name.

One of the unspoken ironies of Steal is that Barnes, the New Dealer and sworn enemy of Nixon confidant Walter Annenberg, was ultimately undone by Democrats like Street and Governor Ed Rendell. At least the governor consented to an on-camera interview, justifying the hijacking of the Barnes on grounds that incontrovertibly contradict the spirit of his will (like the fact that more people will be able to gawk at his collection on the Franklin Parkway). Conversely, representatives of the Pew Charitable Trust, which Argott identifies as the shadowy power player in the takeover of the Barnes, conspicuously declined to participate in the film. (In a further irony, the only political figure in Argott’s film speaking on behalf of Barnes’s intentions is Lower Merion’s Republican congressman Jim Gerlach, to his credit.)

Though he is covering the rarified art world, Argott approaches the Barnes case like a criminal investigation, and with good reason. He also memorably establishes the mind-blowing dimensions of the stakes involved, establishing the term “Barnesworthy.” As art-dealer Richard Feigen explains at a supposedly blockbuster Sotheby’s early modern show, most of the work on display that would soon be bought for millions of dollars would not have merited a second glance from Barnes. Though Feigen himself declined to assign a dollar figure to the entire collection, its value would be estimated in court filings at twenty five billion (with a “b”) dollars. This is what “Barnesworthy” means.

Steal is a smart, persuasive documentary that challenges some previously sacrosanct notions regarding the merit of museums as public institutions. While some of the finer points of estate law might sound dry, Argott makes it all quite compelling, pulling viewers through step-by-step with remarkable assuredness.

Unfortunately, the establishment considers the Barnes’ impending move to downtown Philly a done deal, even though the rag-tag Friends of the Barnes group still fights on. Maybe so, but Argott’s film could make it a pyrrhic victory. It is hard to imagine how anyone could willingly step foot in a Barnes bastardized by machine politics after watching Steal, regardless of the significance of the collection within. Highly recommended, Steal is now available on DVD and streams on Netflix.

Posted on August 24th, 2010 at 11:29am.

Now I’ve got a few more reasons to hate “Fast Eddie” Rendell.

I was telling Joe Bendel today, the only masterpiece I’d otherwise known about from Lower Merion is Kobe Bryant.

This is horrifying. The art belonged to Barnes, not to the city of Philadelphia which sneered at him for collecting it. How ironic that leftist Democrats like Rendell are the ones who want to grab such a valuable collection not because they care about art, but only because they care about the money. This is the most appalling example I have seen yet of the eroding of private property rights in America.

My God, I had no idea that Barnes had so much incredible Impressionist art. That Van Gogh they show in the trailer is amazing, and I was astounded to hear how many Degas and Matisse and Monet he had – all my favorite painters! Can you still see this if you go to Philadelphia, or has it all been locked up in the midst of this dispute?

As for the questionable legality of all this, I am completely appalled that the government would get away with what is basically theft of $25 billion. This would make a great feature film, but since it’s Democrats who are the villains, I guess I won’t expect this as a big Hollywood movie anytime soon.