[Editor’s Note: On the occasion of the 2010 Glastonbury Festival being held in the UK this weekend – the largest music festival in the world, with an estimated 170,000 attendees and 500 music acts – LFM contributor David Ross looks back at the Anglo-Celtic folk revival.]

By David Ross. From Lady Gregory to Lady Gaga … it’s been a depressing hundred years. Let us turn, for momentary solace, to the folk chanteuses of the British Isles, keepers of a tradition “as cold and passionate as the dawn” (Yeats, “The Fisherman”).

Sandy Denny (of Fairport Convention), “Reynardine” and “Tam Lin”: see here and here.

Lyrics to Tam Lin: see here.

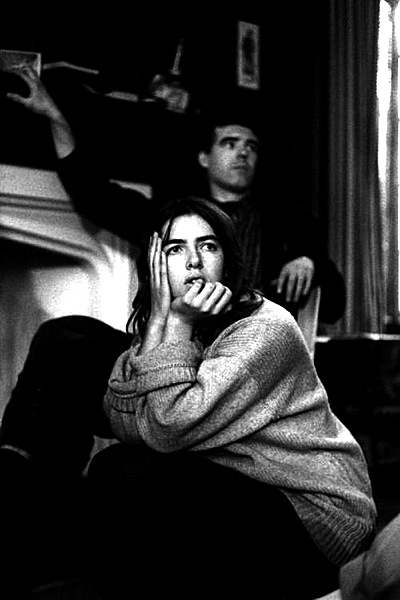

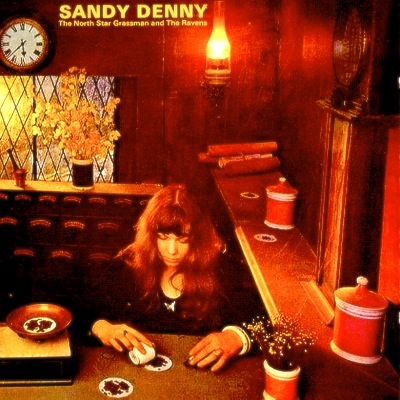

Live footage of Sandy Denny performing a spare, autumnal suite from her first solo album The North Star Grassman and the Ravens (1971). Savor this footage, because there is not much extant footage of Denny performing live; cameras by no means followed her every move. (Compare Warren Beatty’s comment on Madonna in Truth or Dare: “She doesn’t want to live off-camera, much less talk. There’s nothing to say off-camera. Why would you say something if it’s off-camera? What point is there in existing?”)

Tríona Ní Dhomhnail (of Skara Brae and the Bothy Band), “The Maid of Coolmore”: see here.

Jacqui McShee (of Pentangle), “Let No Man Steal Your Thyme”: see here.

Anne Briggs, “She Moved Through the Fair”: see here.

Anne Briggs was the first. A protégé of Bert Jansch during the early sixties, she went from pub to pub playing music that looked back to Queen Elizabeth far more than it looked forward to Sgt. Pepper’s. The old men in tweed drinking their bitter must have been pleasantly surprised. For whatever reason, she did not pursue a recording career in earnest and retired early in life to become a market gardener – which activity, I understand, she pursues to this day. She released three albums, all of which have a stark beauty. She plays an odd syncopated guitar, which at moments heralds Nick Drake. I have no doubt that he listened to her carefully.

The prematurely deceased whom I most lament are Jane Austen, Keats, Shelley, Charlotte Bronte, Kafka, Virginia Woolf, John Coltrane, Jimi Hendrix, Nick Drake … and Sandy Denny. Easily the greatest singer and one of the finest songwriters to emerge from modern England, Sandy died in 1978 at age 31, having fallen down the stairs and suffered a brain hemorrhage. Denny was the guiding genius behind Fairport Convention’s classic albums What We Did on Our Holidays, Unhalfbricking, and Liege & Lief, the last a conceptual masterpiece to rival Sgt. Pepper’s and Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks. All three Fairport albums appeared in 1969, marking what may be the single most exuberantly creative year ever enjoyed by a popular band.

It’s a typical irony of the popular culture that Denny is best known for her duet with Robert Plant on Led Zeppelin’s lyrically goofy but musically gorgeous Tolkienian epic “The Battle of Evermore,” from Led Zeppelin IV. She supplies the song’s eldritch vocal shadowings, which represent, in my opinion, Led Zeppelin’s closest approach to a music of emotion and meaning. Plant, reasonably enough, calls Denny his “favorite singer out of all the British girls that ever were.” Her former bandmate Richard Thompson asks, meanwhile, “Where is Sandy’s cult? Where are the graveside vigilants a la Jim Morrison? The colour supplemental cultural dissections? The South Bank Show eulogies, the bad TV and film biopics telling us who should be important in our lives? Somewhere the taste gurus have failed the flock, have failed to tell us, after twenty years of hindsight opportunity, that Sandy Denny was the greatest British female artist of her generation.”

Denny’s version of the traditional “Matty Groves” on Liege & Lief, incidentally, may be the most purely pre-romantic – which is to say conservative – of all rock songs. Lord Donald’s wife beds the young Matty Groves while her husband is “out bringing the yearlings home.” Finding the lusty couple in flagrante, Lord Donald urges the whelp out of bed:

“Oh I can’t get up, I won’t get up, I wouldn’t get up for my life/For you have two long beaten swords, and I not a pocket knife.”/“It’s true I have two beaten swords, and they cost me deep in my purse/But you shall have the better of them, and I will use the worse/And you shall strike me the very first blow, strike it like a man! /For I will strike the very next blow, I’ll kill you if I can.”

Without much trouble, presumably, he runs the both of them though. In nearly anybody else’s hands, this song would be a parable of ardent youth persecuted by heartless age; in Denny’s treatment, it becomes a parable of position and decorum fiercely and rightly upheld. Denny’s voice steels with passionate nobility as she sings the song’s final lines:

“A grave, a grave,” Lord Donald cried, “to put these lovers in/But bury my lady at the top, for she was of noble kin.”

See here.

If Sandy Denny is the supreme vocalist of the British folk revival, Maddy Prior, of Steeleye Span, Silly Sisters, and the Carnival Band, is the most instinctively traditional. Her voice is uninflected by modern and merely personal nuances of emotion; it has the quality of old stone or November skies. Unfortunately her staggeringly beautiful version of “The Grey Funnel Line” (from the first Silly Sisters album) has been removed from YouTube for copyright reasons. To hesitate is miserly foolishness – waste no time buying the album.

The “Under Review” series – an extensive collection of rock documentaries produced by a UK company called Chrome Dreams – includes informative and intelligent installments on both Sandy Denny and Nick Drake. See here.

The “Under Review” series – an extensive collection of rock documentaries produced by a UK company called Chrome Dreams – includes informative and intelligent installments on both Sandy Denny and Nick Drake. See here.

An essential discography of the Anglo-Celtic folk revival:

The Pentangle, The Pentangle (1968); Fairport Convention, What We Did on Our Holidays (1969); Fairport Convention, Unhalfbricking (1969); Fairport Convention, Liege & Lief (1969); Nick Drake, Five Leaves Left (1969); Nick Drake, Bryter Layter (1970); Steeleye Span, Hark! The Village Wait (1970); Fairport Convention, Full House (1970, sans Sandy Denny); Anne Briggs, Anne Briggs (1971); Anne Briggs, The Time Has Come (1971); Sandy Denny, The North Star Grassman and the Ravens (1971); Skara Brae, Skara Brae (1971); Anne Briggs, Sing a Song for You (1973); Nick Drake, Pink Moon (1973); The Bothy Band, The Bothy Band (1975); Clannad, Clannad II (1975); Tríona Ní Dhomhnail, Tríona (1975); The Bothy Band, Old Hag You Have Killed Me (1976); Clannad, Dúlamán (1976); The Bothy Band, Out of the Wind, Into the Sun (1977); Silly Wizard, Caledonia’s Hardy Sons (1978); Silly Wizard, Wild & Beautiful (1981); Silly Wizard, Kiss the Tears Away (1983); Andy M. Stewart, By the Hush (1983).

Posted on June 27th, 2010 at 12:21pm.

Interesting post, David. I did not realize how important some of these singers were. The ’60s and ’70s were so dominated by rock, disco, punk, etc. that the softer side of the music scene that was inhabited by these talented folk singers has been forgotten.

Do you think that some of this has to do with the fact that most of these singers were women, and that from the ’60s on the music scene (and the culture) grew more misogynistic and male-dominated and did not know how to appreciate them sufficiently?

None of this music was ever very popular; only Clannad went on to become a big seller, and this by becoming an annoying purveyor of New Age mistiness. The music of the Anglo-Celtic folk revival was serious, traditional, and in its way difficult; it required attention and receptivity to the darker emotions and a certain respect for the past. Misogyny may have played a part, but the more basic point is that this music was entirely at odds with the slickly shallow commercialism that remade popular music during the 70s (see Fred Goodman’s excellent history of this sell-out, Mansion on the Hill). Nothing could have seemed more retrograde and out-of-phase than, say, Sandy Denny lamenting the fate of Mary, Queen of Scots, as she does so beautifully in “Fotheringay” (Fotheringay was the castle where Mary was imprisoned).

British folk music has long been overdue for some recognition, and these ladies were the cream of the crop.

I find these singers’ defiant traditionalism, their celebration of British history and myth in the face of all modernity, oddly moving. There is a quality of heroism to their flying in the face of “slick commercialism,” as you put it so well above.