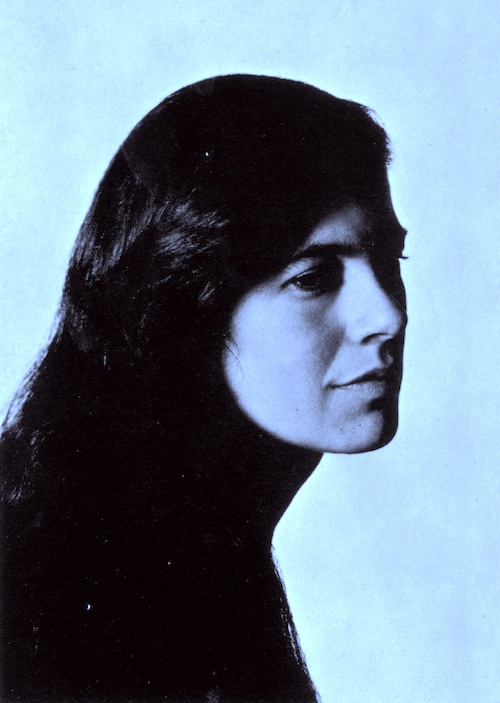

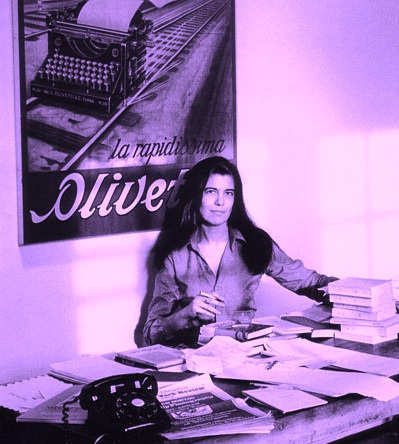

By David Ross. Sigrid Nunez was during the mid-1970s Susan Sontag’s secretary and her son David Rieff’s lover. Her recently published memoir Sempre Susan (read a racy excerpt here) has improbably returned Sontag to the spotlight, just when her long slow fade seemed to have begun in earnest. A mandarin even by the standards of the intelligentsia, Sontag did much to instate the European art film as a phenomenon of the intellectual vanguard during the 1960s and 1970s.

So too her look and bearing codified what it meant – and still means – to be a ‘serious intellectual.’ Sontag always struck me as feline: elegant, self-contained, sharp-clawed, well-groomed (intellectually and physically). To extend my metaphor, I imagine her as a silky Persian cat perched atop a garden wall, occasionally glancing with disdain at all the mere dogs clumsily being dogs below – romping idiotically, smelling each other’s behinds, crapping in the bushes, having fun.

This semester I gave my students Sontag’s essay on Godard’s Vivra Sa Vie, one of several self-consciously ‘important’ essays on film anthologized in Sontag’s breakthrough volume Against Interpretation (1966). I admire its elegant minimalism (rather like the movie itself), but I find it lacking in heft and emotional engagement (again like the movie itself). I paired Sontag’s essay with our own Jennifer Baldwin’s photo-essay on Vivra Sa Vie, which in many ways I consider more satisfying because more immediate and more human. My students laughed at Jennifer’s cri de femme: “I want Nana’s fuzzy black coat.” Sontag did not make the students laugh. I wonder if she ever made anybody laugh. Possibly not.

Virginia Woolf said of Yeats, “Wherever one cut him, with a little question, he poured, spurted fountains of ideas.” This Titanism – this quality of thinking and being on a grand scale, of bringing to bear the whole of one’s self – is the hallmark of the great intellectuals. Sontag never pours or spurts. She makes a clinical exercise of what should be a vast excitement.

In terms of film criticism, I favor Pauline Kael, if only because she understood the cardinal romantic truth that intellect is merely an expressive device of the personality. Kael suffers from serious lapses in taste and judgment, but her wild and woolly prose is more alive than Sontag’s and her passions more transparent and seemingly sincere. Sontag was more sophisticated in her range of interests and enthusiasms, but only more serious and ambitious in a way. She was interested in exploring her own capacity for exploration, interested in her own mind and what it could figure out. Her form of criticism is a kind of intellectual ceremony, a kind of Japanese tea ceremony in which Sontag dispenses herself in refined and smallish doses. In the end, Sontag is a bit too astringent for my taste. A film should not be an intellectual puzzle or a pretext for critical experiment; it should be a hub of personal meaning.

I reread yesterday Sontag’s “Notes on Camp,” also from Against Interpretation. It’s a brilliant little piece, but it says far more about Sontag herself than about camp. Its real content is the curious involutions of its own form and expression. It is about itself, and in this regard functions more like a poem – a clever but dry one – than like criticism properly defined.

Sontag’s politics were, of course, faithful to the milieu of intellectual Manhattan. “All her views were left-wing commonplace,” writes Joseph Epstein, “noteworthy only because of her extreme statement of them.” On September 24, 2001 – in what may be the most infamous of her numerous infamous utterances – she opined in The New Yorker:

The disconnect between last Tuesday’s monstrous dose of reality and the self-righteous drivel and outright deceptions being peddled by public figures and TV commentators is startling, depressing. The voices licensed to follow the event seem to have joined together in a campaign to infantilize the public. Where is the acknowledgment that this was not a ‘cowardly’ attack on ‘civilization’ or ‘liberty’ or ‘humanity’ or ‘the free world’ but an attack on the world’s self-proclaimed superpower, undertaken as a consequence of specific American alliances and actions? How many citizens are aware of the ongoing American bombing of Iraq? And if the word ‘cowardly’ is to be used, it might be more aptly applied to those who kill from beyond the range of retaliation, high in the sky, than to those willing to die themselves in order to kill others. In the matter of courage (a morally neutral virtue): whatever may be said of the perpetrators of Tuesday’s slaughter, they were not cowards.

Our leaders are bent on convincing us that everything is O.K. America is not afraid. Our spirit is unbroken, although this was a day that will live in infamy and America is now at war. But everything is not O.K. And this was not Pearl Harbor. We have a robotic President who assures us that America still stands tall. A wide spectrum of public figures, in and out of office, who are strongly opposed to the policies being pursued abroad by this Administration apparently feel free to say nothing more than that they stand united behind President Bush. A lot of thinking needs to be done, and perhaps is being done in Washington and elsewhere, about the ineptitude of American intelligence and counter-intelligence, about options available to American foreign policy, particularly in the Middle East, and about what constitutes a smart program of military defense. But the public is not being asked to bear much of the burden of reality. The unanimously applauded, self-congratulatory bromides of a Soviet Party Congress seemed contemptible. The unanimity of the sanctimonious, reality-concealing rhetoric spouted by American officials and media commentators in recent days seems, well, unworthy of a mature democracy.

Those in public office have let us know that they consider their task to be a manipulative one: confidence-building and grief management. Politics, the politics of a democracy – which entails disagreement, which promotes candor – has been replaced by psychotherapy. Let’s by all means grieve together. But let’s not be stupid together. A few shreds of historical awareness might help us understand what has just happened, and what may continue to happen. “Our country is strong,” we are told again and again. I for one don’t find this entirely consoling. Who doubts that America is strong? But that’s not all America has to be.

To which I can only respond: “disconnect” as a noun? What was she thinking?

Joseph Epstein, reviewing Nunez’ memoir in the Wall Street Journal, vents what seems to be decades’ worth of pent up exasperation with Sontag’s stylish preening. Epstein is not surgical enough to be devastating, but this comment has its little blade of truth: “People speak of ideas whose time has not yet come; hers was a talent for promoting ideas that arrived precisely on time.”

My pen-pal of sorts David Zincavage knew Sontag – a little – and comes to her defense with an affectionate reminiscence (see here). Mr. Zincavage is not what you’d call a man of the left, and his weakness for Sontag has its bemusing aspect. In the end, of course, he’s right to adore a beautiful and brainy woman; politics are a base excuse for withholding our tribute. Mr. Zincavage writes:

Today, when I watch Last Year at Marienbad or L’Aventurra, when I look into a novel by Nathalie Saurraute, I feel rather the way a veteran of a lost, romantic cause, like some aged grenadier of the wars of Napoleon, must feel thinking back and remembering Austerlitz or Marengo. I smile ruefully at the memory of being young and naive enough to believe that this sort of thing would come to anything, but I also remember the aspirations and the hopes we entertained back then.

Susan Sontag is extremely vulnerable to all the criticisms to which mainstream Western high culture in the second half of the last century is vulnerable. She was naively romantic, prone to left-wing postures and insanity, and not above following the community of fashion herd into disgraceful positions. But she was still a heroine who, at times, at least, brought great honor to that same high culture and the same civilization her entire class was usually busy trying to destroy.

Mr. Zincavage is correct enough: Sontag was sometimes blind, but never stupid and never lazy. If she betrayed her country in certain ways – had trouble standing shoulder to shoulder with it – she never betrayed the cause of the mind.

Posted on April 16th, 2011 at 11:33am.

My taste for criticism formed when I found a pile of Cinefantastique magazines at a church book sale when I was in my early teens.

I’ve always found the art interesting, if not a little self-absorbed. It always seemed more interested in itself than the actual subjects. That being said, I think modern criticism could use a little more refinement, which is why I visit this site.

As for Sontag, I always think of the Crash Davis quote in Bull Durham whenever I think of her — because it’s kind of how I feel. That’s not to say I dismiss her — she has always showed just enough intellectual honesty to provoke real thought.

Her editorial from 2001 posted above is a great example. After 9/11, it was important for a bit of self-reflection, which she helped provide with the example of the U.S. bombing campaigns in Iraq. That bit of policy is detestable, but she stops short in teeing up the man responsible for instituting that policy, and who — by UNICEF’s reports — killed hundreds of thousands of Iraqis, women and children included.

That, of course, was Bill Clinton. I don’t want to get political, but to me his exclusion from the piece is an example of the intellectual void of the pseudo-intellectual left. There are just certain sacred cows, and certain villains, and that’s then end of the story.

Her assessment of the 9/11 perpetrators is also indicative of this. Certainly, those men were not cowards, but they were and ARE believers. The ideology needs to be seriously discussed and not through a veil of political correctness. It would’ve been nice if Sontag provided more historical context — like the Nakhla Raid, the Battle of Trench, or the Battle of Tours.

I guess Mr. Zincavage’s remarks about Sontag are perfect.

Thanks so much for the kind word about our efforts, Vince.

Typo alert: Should that be secretary instead of sectary in the opening graf?

Thanks, I’ll take care of that …

I recently read about half the essays in Against Interpretation, my first experience with Sontag. I found them quite interesting and provocative, though I wasn’t sure I agreed with many of them. I was struck, though, by her afterward to the book, written in 1996. There she makes the usual point that she never thought the boo would still be read 30 years later, etc. but she also goes on to suggest that her ideas and convictions of the time were rather naive. People in the sixties were full of utopian ideas that never came to pass, and now that time is really and truly past and can never be regained. This might be just the usual liberal regret, but she makes the point that the culture as a whole has greatly declined since then, that the new era is not as vibrant and intelligent and high-minded as it used to be. “The modern,” she says, “was still a vibrant idea. (This was before the capitulations embodied in the idea of the ‘post-modern’.)” She tries to suggest this is the fault of consumer capitalism, something which no doubt has played a role in the increasing materialism and lessening of spiritual values in the culture, but the gnawing feeling comes through that maybe it was her generation itself that caused the problem.

“It is not simply that the Sixties have been repudiated, and the dissident spirit quashed, and made the object of intense nostalgia. . . Something that it would not be an exaggeration to call a sea-change in the whole culture, a transvaluation of values–for which there are many names. Barbarism is one name for what was taking over. Let’s use Nietzsche’s term: we had entered, really entered, the age of nihilism.”

“Still, I urge the reader not to lose sight of . . . the larger context of admirations in which these essays were written. To call for an “erotics of art” did not mean to disparage the role of the critical intellect. To laud work condescended to then as “popular” culture did not mean to conspire in the repudiation of high culture and its complexities.”

This struck me as a sentiment Mr. Ross could agree with quite strongly.