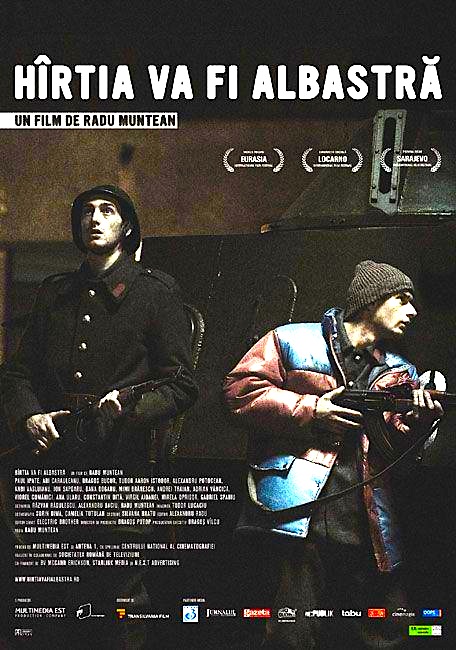

By Joe Bendel. In 1989, the Romanian military received the orders all soldiers serving behind the Iron Curtain dreaded most. They were commanded to fire upon their fellow countrymen. Some did so, to an extent, but many more sided with the Revolution. Radu Muntean captures the chaotic anarchy in the hours immediately following the fall of Ceaușescu in his distinctly anti-heroic The Paper Will Be Blue (trailer here), which screened as part of a Muntean retrospective on the closing night of the Sixth Annual Romanian Film Festival, co-presented by the Romanian Cultural Institute and the Film Society of Lincoln Center.

By Joe Bendel. In 1989, the Romanian military received the orders all soldiers serving behind the Iron Curtain dreaded most. They were commanded to fire upon their fellow countrymen. Some did so, to an extent, but many more sided with the Revolution. Radu Muntean captures the chaotic anarchy in the hours immediately following the fall of Ceaușescu in his distinctly anti-heroic The Paper Will Be Blue (trailer here), which screened as part of a Muntean retrospective on the closing night of the Sixth Annual Romanian Film Festival, co-presented by the Romanian Cultural Institute and the Film Society of Lincoln Center.

Blue’s flashback format tells viewers right up front this night will end badly. Muntean then rewinds a few hours to show how events reached this point. Though Ceaușescu has been deposed, the military is not sure what to make of it. The revolutionaries have seized the television studio and many officers and enlisted men have volunteered to defend it from Communist Loyalists – or as the call them, terrorists. If you are wondering how to tell one side from the other, then you have just pinpointed the crux of Blue.

Militia (state copper) Lt. Neagu’s armored squad vehicle has been assigned to patrol a sleepy suburb well away from the action. However, one of his men from a politically connected family, Costi Andronescu, has deserted to join the forces defending the TV station. Fearing he will be disciplined for the actions of his subordinate, Neagu and his men venture into the maelstrom, hoping to bring back Andronescu in time for morning roll call. As they careen through the streets of Bucharest, allegiances become increasingly confused.

With its gritty docudrama-style and Kafkaesque absurdity, Blue bears many of the hallmarks of the so-called Romanian New Wave. However, there is no slack in this picture. It is tight and tense, holding a firm grip on viewers even though they know exactly where it ends. Muntean vividly captures both the claustrophobia within the armored car, and the disorienting commotion unfolding outside. The film also resists easy political labels, revisionist or otherwise, but as is often the case in the Romanian Wave, bureaucracy and authority figures take a real skewering.

Adi Carauleanu is fantastic as the world-weary but compulsively cautious Neagu. Through his fatalism and wariness, the audience gets a sense of the pent-up frustration resulting from decades of service under Communism. Though a bit stiff on-screen, Paul Ipate has some finely turned moments as Andronescu as well. More than anything, though, Blue is about conveying the in-the-moment feeling of a particularly time and place, in all its madness.

Blue is an excellent representative of Romanian film for a number of reasons. It certainly dramatizes a critical moment in recent history, but it also proves that the films of the Romanian New Wave are not necessarily long, slow, or moody. Raw and visceral, Blue packs a punch. Its title also makes perfect sense in retrospect, but to explain why would be telling. Blue closed the 2011 Romanian Film Festival at the Walter Reade Theater this past Sunday (12/6), with a special post-screening Q&A with Muntean.

•

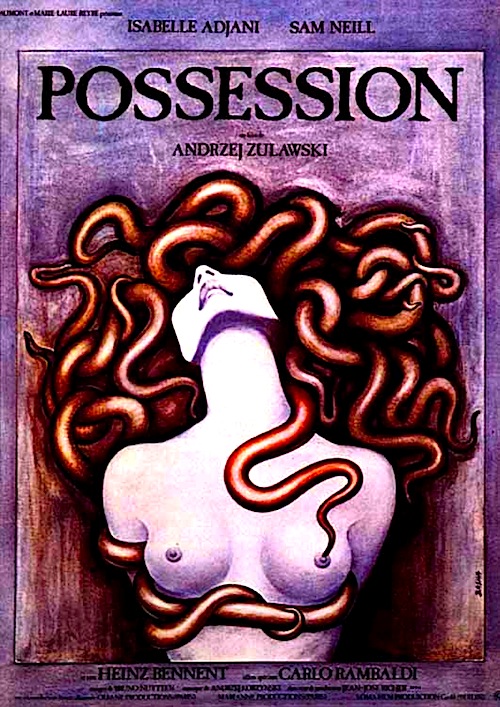

East German border guards can see Mark and Anna’s apartment from their posts along the Berlin Wall. It ought to be the perfect setting for the dissolution of their marriage. However, their union will not be merely severed. It will be torn limb from limb in former Andzrej Wajda protégé Andrzej Żuławski’s notorious art-house pseudo-horror film Possession (trailer here), which finally opened theatrically in all its uncut, restored glory at New York’s Film Forum this past Friday.

East German border guards can see Mark and Anna’s apartment from their posts along the Berlin Wall. It ought to be the perfect setting for the dissolution of their marriage. However, their union will not be merely severed. It will be torn limb from limb in former Andzrej Wajda protégé Andrzej Żuławski’s notorious art-house pseudo-horror film Possession (trailer here), which finally opened theatrically in all its uncut, restored glory at New York’s Film Forum this past Friday.

Previously released in a butchered shorter cut, Possession has something of a reputation—and rightly so. Essentially, it is everything Lars von Trier’s The Antichrist was billed as, raised to the power of ten. If that gives you any trepidation whatsoever, then Possession is not for you – but if you are open to it, take a deep breath and let’s get into it.

Mark is some sort of freelance spy returning home after a long assignment. Strangely, though, his wife Anna is less than thrilled to see him. In fact, she can hardly stand to be in the same room with him. Indeed, it turns out there is another man she is determined to leave Mark for. This sends her insecure husband into a self-destructive bender, involving violence directed towards her and to a greater extent, himself. Obviously this is not a great environment for their son Bob, the symbol of innocence throughout the film, whom Mark deliberately uses as a weapon against Anna.

When he finally rouses from his stupor, Mark hires a private detective agency that follows Anna to a creepy unfurnished apartment in a down-market neighborhood. While Anna might want some space from Mark, she seems to be enraptured by a “thing.” Rather intimately, in fact. This is where things start getting weird and even bloodier.

Mark and Anna could probably use a psychiatrist and an exorcist. They certainly should not be around powerized kitchen appliances. What unfolds is absolutely harrowing and completely bizarre. Żuławski’s control of the audience is masterful. He simultaneously cranks the tension up to nosebleed levels, while constantly bombarding viewers with jolt-inducing imagery. You cannot really call it a horror film, but that is probably the closest applicable label.

The combination of Sam Neill and Isabelle Adjani is the kind of intriguing pairing that might convince cautious cineastes to take a chance on Possession. Both leads totally go for broke throughout the film, but it would probably be more accurate to say they develop a convincing anti-chemistry together.

Still, Adjani also has some remarkably delicate scenes with Neill as Helen, Anna’s doppelgänger (don’t ask, it would take too long to explain). Indeed, her exquisitely sensitive and vulnerable appearance makes her characters’ transgressive behavior all the more jarring, especially her five minute freak-out in the West Berlin metro. Frankly, it feels more like twenty-five minutes; just when you think it cannot get any more shocking, she reaches a new level. However, the raw, visceral power of her performance is undeniable, justly recognized at the Cannes Film Festival with the best actress honors.

Adjani’s longtime partner, cinematographer Bruno Nuytten, gives the film a classy, polished look that suggests auterist genre classics from the likes of Polanski and Kubrick. Yet, for all its blood and inhumanity, Possession is not a scarring film for anyone with a fair number of cult films under their belt. Though there is violence, it is never committed out of sadism (just why characters do certain things is another matter entirely). Nor is Possession a nihilistic film. Notions of right and wrong, good and evil, have very real meaning in this world. It is just the case that the latter have the overwhelming upper-hand against the former.

Possession is a true experience. It is draining to watch, but when it is over, you know you have seen a film. Big, bold, and intensely personal, it is a genuine masterwork from Żuławski. Highly but judiciously recommended to those who fully understand what they are getting into, Possession began its special one week run at Film Forum this past Friday (12/2).

Posted on December 5th, 2011 at 2:45pm.