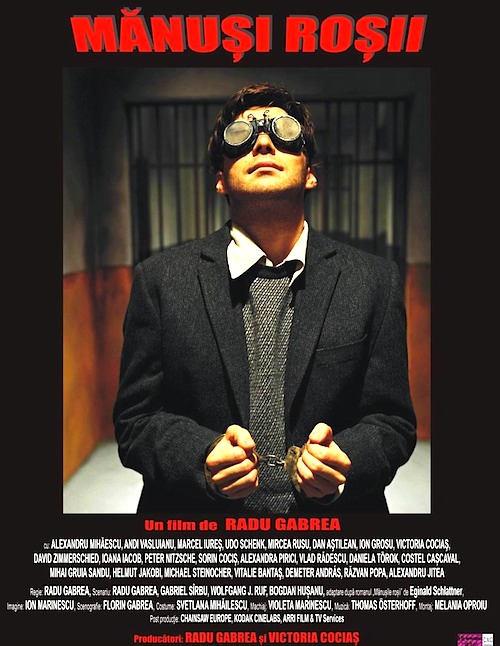

By Joe Bendel. It was hard being part of Romania’s Saxon minority, particularly in the immediate post-war years. Emboldened by the Soviet suppression of the Hungarian Revolution, the Romanian Communists began targeting the German-speaking minority. Though as a group they were disproportionately anti-Communist (and for good reason), this was not the case for young leftwing student Felix Goldschmidt. His lengthy imprisonment, interrogation, and trial testimony are dramatized in Radu Gabrea’s Red Gloves (trailer here), which screens today (Thursday, 12/1) during the 2011 Romanian Film Festival, presented by the Film Society of Lincoln Center and the Romanian Cultural Institute.

By Joe Bendel. It was hard being part of Romania’s Saxon minority, particularly in the immediate post-war years. Emboldened by the Soviet suppression of the Hungarian Revolution, the Romanian Communists began targeting the German-speaking minority. Though as a group they were disproportionately anti-Communist (and for good reason), this was not the case for young leftwing student Felix Goldschmidt. His lengthy imprisonment, interrogation, and trial testimony are dramatized in Radu Gabrea’s Red Gloves (trailer here), which screens today (Thursday, 12/1) during the 2011 Romanian Film Festival, presented by the Film Society of Lincoln Center and the Romanian Cultural Institute.

Goldschmidt tried to believe the excesses of Romania’s so-called “obsessive decade” were an aberration that would soon give way to true socialism. He also craved acceptance. That would be more than enough for his interrogators to work with. In truth, Goldschmidt’s politics were a little slippery. He had associated with several nonconformist elements, but his relationship with them was somewhat ambiguous. In particular, he claims to resent the now banned author Hugo Huegel for stealing his girlfriend, but viewers witness decidedly intimate scenes shared by the two men.

Frankly, Goldschmidt is fairly wishy-washy, which makes him more vulnerable to the tactics of his captors. He seems especially eager to please the German speaking Major Blau, yet for a time he resists denouncing his friends and colleagues. Still, even a strong personality can only hold out for so long—and Goldschmidt is not such a man.

Based on fact, but adapted from the novel by Enginald Schlattner, a Saxon-Romanian Lutheran pastor, Gloves is a deeply and pervasively tragic film. Arguably, Gabrea has become something akin to Romania’s cinematic conscience, having helmed a adaptation of a previous Schlattner Saxon-Romanian novel – as well as the Holocaust-themed drama Gruber’s Journey – and documentaries about Romania’s Yiddish cultural legacy.

With Gloves, Gabrea focuses squarely on the interrogation process, vividly portraying the breakdown of Goldschmidt’s soul. Though there are frequent subsidiary flashbacks within the main narrative flashback, it is all a bit stage-like, featuring its cast of characters in a confined setting. Yet it is an effective arena to explore the terrors of Romania’s communist past, particularly through the hard insights offered by a former judge and a priest who briefly share Goldschmidt’s cell.

Though it is essentially by design, Goldschmidt is still a rather hollow figure nonetheless, never really brought to life by Alexandru Mihaescu. In contrast, Udo Schenk is absolutely electric as Blau. He deserves to be an internationally star, but the SS and Communist officers he has played for Gabrea are difficult to embrace, despite the screen charisma he brings to them.

Bitterly ironic and brutally honest, Gabrea’s film is—to use a loaded term from Gloves—a “cathartic” work. It is also a high quality period production that might come as a welcome respite to patrons tiring of the Romanian New Wave aesthetic, even with its grim subject matter. Respectfully recommended, it screens Thursday night (12/1) during the 2011 Romanian Film Festival at the Walter Reade Theater.

•

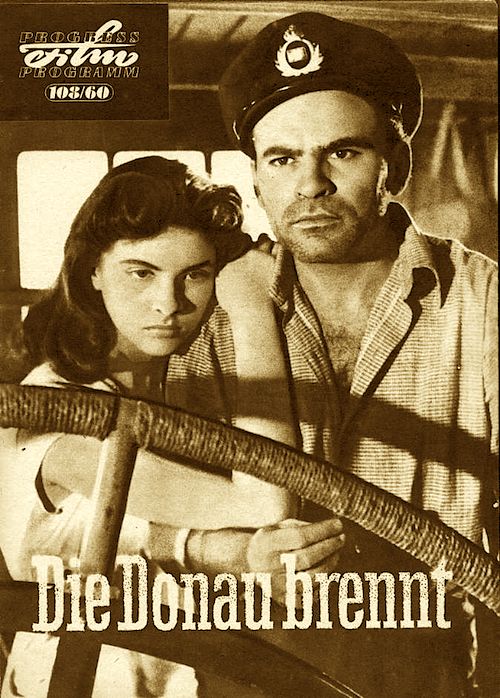

Given Romania’s shifting positions during WWII, it was a bit tricky setting a Communist-era propaganda film during that time, but the recently deceased Liviu Ciulei managed to do just that. For his second feature, the renowned theater director combined Casablanca with Wages of Fear, adding a pinch of Party propaganda for seasoning. A ripping tale of war and intrigue, Ciulei’s Danube Waves screens as part of the sidebar tribute to the filmmaker at the 2011 Romanian Film Festival, presented by the Film Society of Lincoln Center and the Romanian Cultural Institute.

Mihai is barge captain who does not trouble himself over politics. Nor is he much concerned about the poor substitutes for sailors he forces to sweep for mines. He just wants to get home to his young wife Ana. Though expendable crewmen are getting harder to recruit, the Germans are willing to provide a prisoner for his use. He chooses Toma, because the supposed criminal is certainly able-bodied and claims to have served on a ship before.

However, Ana can tell right away Toma does not know port from starboard, but he is a quick enough study to fool Mihai. Suspecting he is more than a common thief, a conspicuous sexual tension develops between Toma and Ana that Mihai deals with through heavy drinking as the barge loaded with German arms approaches a known minefield.

Of course, Toma is an agent of the Communist partisans, which gives the film an opportunity to periodically remind viewers just how deeply the Party loves us and how much it has sacrificed for Romania. Though hard to miss, these messages easily could have been more didactic.

The rest of the film is quite tightly executed. There are some real white-knuckle moments as the barge negotiates the bobbing mines and the dialogue (per the translated subtitles) is surprisingly sharp and even snippy at times. In a powerful performance, director Ciulei’s Mihai is an intense salt-of-the-earth screen presence, like Rick Blaine by way of Stanley Kowalski. In her film debut, Irina Petrescu nicely balances the intelligence, naivety, and sexuality of Ana. Though a bit stiff, Lazar Vrabie has a craggy Robert Stack quality that works rather well for Toma. After all, Communist heroes are supposed to be rigid and unyielding.

Danube is such a good film noir, even the state film authorities could not undermine it. Grigore Ionescu’s black-and-white cinematography is appropriately cool and moody, while the love triangle frankly gets kind of hot. As a bonus, there is even a rendition of “The Internationale.” Highly recommended for old fashioned movie lovers who can parse the occasional propaganda salvo, Danube screens this Friday (11/2) as part of the 2011 Romanian Film Festival at the Walter Reade Theater, with a special introduction from Petrescu.

•

The Ceaușescu years were not kind to those with an independent spirit or a competitive urge. Even the experience of victory was fraught with irony, but Gregor Totock would not know. The swimmer will have a rematch with his old nemesis, the Danube River, in Anca Miruna Lăzărescu’s Silent River (trailer here), the clear standout of the shorts program at this year’s Romanian Film Festival, presented by the Film Society of Lincoln Center in conjunction with the Romanian Cultural Institute.

Years ago, Totock tried to swim to the relative safety of Yugoslavia, via the Danube. It turned out badly for him—and even worse for his female companion. Several years later, the “rehabilitated” Totock is ready to take another shot at the river. Vali, a telephone authority employee, has clearance to be in the border zone, while he has contacts in Serbia who can smuggle them to Germany. Totock only reluctantly accepts the other man as a partner, adamantly refusing whenever Vali speaks of bringing his wife with them. Of course, Totock’s distrust of his companion is partly validated, greatly complicating their escape attempt.

Watching Silent will make viewers feel damp and chilly. It is grim and naturalistic, yet undeniably tense and even stylish. It vividly conveys the omnipresent fear of the Communist years that could not be called ‘paranoia,’ because it was firmly rooted in reality. Toma Cuzin is a genuinely intense, gaunt looking screen presence, suggesting the power of a coiled spring ready to erupt. Established Romanian actor Andi Vasluianu also makes quite an impression, playing Vali with convincing nervous energy, without ever becoming ticky or mannered.

In marked contrast to Silent’s grittiness (the real socialist realism), Victor Dragomir’s Strung Love takes a gentler, more nostalgic look back at the supposed “Golden Age.” Viorel Petre is a smart, sensitive underachiever at his industrial high school, recruited by the principal, Comrade Badea, to defeat the school bully in a rivet making contest, and hopefully win over his crush in the process.

Much gentler in its satire, Strung seems to have a perverse fondness for the time when rivets were exalted in classrooms for playing a key role in the state’s industrial plan. Still, the political struggle between the principal and the metal-working teacher clearly depicts the pettier tendencies of Communist-era bureaucracy. Strangely stylized, Strung’s cast deliberately (one assumes) looks far too old for high school, but they scrupulously stay in character and never wink at the audience. Indeed, its goofy, light-hearted spirit is rather enjoyable, even if it largely dresses up the experience of living under the Ceaușescus.

This year’s Romanian short film program is unusually strong, also featuring Ioana Uricaru’s notable Stopover, a sly, subtler take on the basic premise of Spielberg’s Terminal, written by Cristian Mungiu of 4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days renown. However it is more of vignette. Silent is a fully conceived and realized film. One of the nominees for best short film at the 2011 European Film Awards, it is a work of a very high caliber, whereas Strung is just a lot of fun. All three screen together as part of the shorts program at the 2011 Romanian Film Festival at the Munro Film Center Amphitheatre this Friday and Saturday (12/2 & 12/3)—and take note: admission is free.

Posted on December 1st, 2011 at 2:31pm.