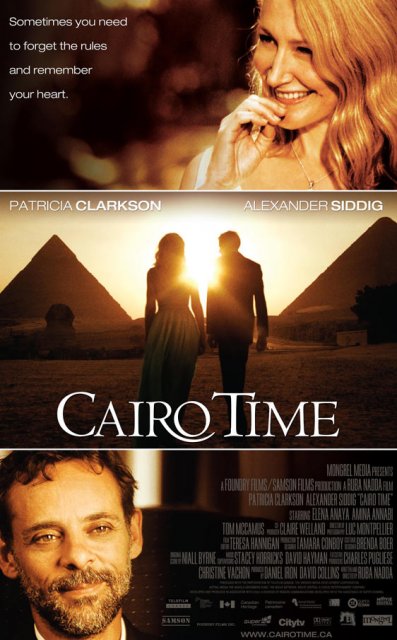

By Patricia Ducey. Time in Cairo is slow. Very slow. Glances are exchanged. Background concertos are heard. Sparks, however, are not ignited, ever, between Juliette (Patricia Clarkson), an American magazine editor and Tareq (Alexander Siddig of Syriana), her supposed Romeo in Cairo Time.

By Patricia Ducey. Time in Cairo is slow. Very slow. Glances are exchanged. Background concertos are heard. Sparks, however, are not ignited, ever, between Juliette (Patricia Clarkson), an American magazine editor and Tareq (Alexander Siddig of Syriana), her supposed Romeo in Cairo Time.

This is not Shakespeare, or even English Patient (a great weepy if ever there was one). This is one nuanced love affair.

Juliette and Tareq represent archetypes of the East and West, yet they are actually more alike than different: both inhabit internationalist circles – Tareq just recently retired from the U.N., where he came to know Juliet’s husband (a UN operative in Gaza), and Juliet herself a feminist women’s magazine editor. Not much of a culture clash here. At a few points in the film Tareq lightly (and rightly) scolds Juliet for her easy outrage over a few social problems in Egypt. This hints at further story is to come, perhaps a real discussion of custom and culture, but nothing develops. (The Last King of Scotland, by contrast, brilliantly portrayed the deadly consequences of feckless liberalism in its main character.)

Juliette arrives in Cairo to await her husband’s arrival from Gaza so they can enjoy a long dreamed of vacation together. He is delayed, though, by trouble in the refugee camp he manages – so he asks his old friend Tareq to see after his wife until he can join her. Juliette seems anxious, tentative and tongue-tied from the start – odd behavior for a successful magazine editor. We wonder why – middle age crisis, bad marriage, illness? – but we never find out. She loves her husband, children, and her job. Tareq tries to draw her out but she rebuffs him. Later, though, she mystifyingly shows up at his men-only coffeehouse to visit him – not once but twice.

This fog of ambiguity never clears, and slows the movie down to a crawl. Juliette wanders the streets alone, inexplicably tossing aside her husband’s warnings about women traveling alone. Naïve, self-destructive? One can only ponder. This behavior does reveal the only people who seem to know who they are, sadly: the bands of leering men on the Cairo streets who consider her, a Western woman alone on the street, as something south of “available.”

Juliette finally takes action after her husband is delayed again and again. She hops a bus to the border and to Gaza to find him, but the Egyptian police stop the bus and send her back to the hotel; they realize the situation in Gaza is dangerous. As Juliette follows the police, her seatmate – a young Egyptian woman – stuffs an envelope into Juliette’s hands and implores her to deliver it to her lover back in Cairo. Again, hints at a story: tension, mixed up in politics, danger – but this too goes nowhere. She gives the letter to the young woman’s lover.

The narrative of any melodrama demands some rupture of the moral code. English Patient’s doomed love story was played out on the canvas of a World War, when the old world order was collapsing in England and the Middle East. The lovers in English Patient violated every norm of class, race, gender and sexual orientation and died in agony for their transgressions. Patricia Clarkson’s protagonist, on the other hand, is a modern Western woman and thus is left with no moral code to rupture whatsoever. What will she lose if she betrays her husband, what would happen if she did betray him with Tareq? Not much. Tareq is an Egyptian Muslim who is kind of secular, kind of not. We are not quite sure what his moral code is either, or if he has one. Perhaps this is why the greatest doomed love stories take place at least pre-1950.

Canadian writer/director Ruba Nadda has underwritten both the characters and the story. The characters’ physicality – walking, talking, eye gazing, walking, talking – as well as their sparse dialogue reveal little. Clarkson and Siddig do their best but have little to work with.

My inner writer asks, what do these characters want? Apparently not each other. Or at least not very much. Perhaps Juliette will remain faithful to her husband, perhaps not, but it is of no real import to a woman in the grips of such anomie. Tareq was content pre-Juliette and is content post-Juliette. I am not asking for these characters to outrun a fireball or gun down CIA assassins – I just want to know why their lives and loves matter.

Posted on August 10th, 2010 at 9:36am.

I saw the trailer for this film earlier this summer and was wondering if it would be any good. of course I was expecting that if it was set in the Middle East that there would be the inevitable political digs, and so I wasn’t interested in seeing it. However, from your review, it seems they didn’t even have the energy to do that.

Hollywood can’t do romance anymore, but I don’t think it’s because their are no moral codes left to break. It’s because the industry is run by fan boys and they hate romance and anything to do with women.

First of all – great review as always, Pat. I wanted to jump in and comment on the issue of why Hollywood and even the indie film world have so much trouble with making romances nowadays. It’s not just because fan-boy tastes dominate the industry (though that’s certainly true), it’s also because the feminists have bought the line that romance, love and marriage are somehow “backward” issues for them that carry with them demands for traditional domesticity that will curtail their freedom. That’s why you have such awkward pseudo-romances like “Cairo Story.” I mean, come on, how hard can this stuff be to do?

There are more women executives in Hollywood today than ever before, and yet they’ve never had more trouble making romances or movies for women. It really makes you wonder.

I agree, Govindini. The former transcendent love stories, doomed or not, did imply a dimension of spirituality, or something above the utilitarian. Feminism now seems to me to be all about draining relationships of all that stuff. Love is reactionary!