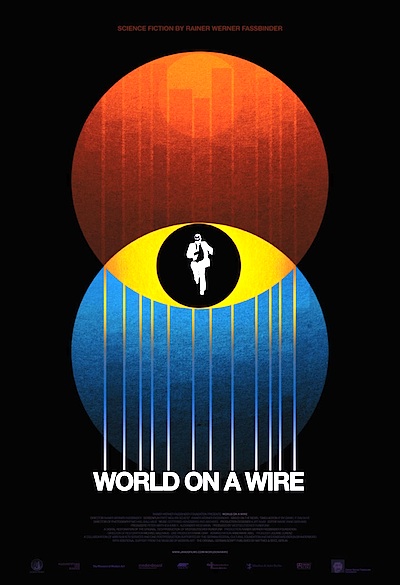

By Joe Bendel. Fred Stiller does not know Kung Fu. However, he learns some hard truths about The Matrix decades before the Wachowskis sent Keanu Reeves down the rabbit hole. In fact, he helped develop what is known as the ‘Simulacron’ in Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s newly restored two-part 1973 television miniseries, World on a Wire, which opens theatrically this Friday in all its three and a half hour glory at the IFC Center in New York and in select art house theaters nationwide.

Prof. Henri Vollmer’s death was suspicious. The disappearance of his friend, Günther Lause, the head of security for his supposedly nonprofit research facility, is even more so. At least people remember Vollmer as the man who created the Simulacron. However, Lause seems to have disappeared entirely from people’s memories after literally vanishing in the midst of a conversation with Stiller, Vollmer’s trusted deputy.

In a case of good news-bad news, the Machiavellian foundation head promotes Stiller to Vollmer’s position, but the researcher is equally unreceptive to proposed commercial applications for the Simulacron. Essentially a virtual environment populated by six thousand artificial intelligence programs, the Simulacron is designed to project social development twenty years into the future. None of the sentient identities knows they are artificial, except Eisenstein, the designated contact program. As one would expect, he is a rather morose collection of code, never particularly happy to see Stiller or his lead programmer when they helmet up to pay him a visit.

Anyone who has seen the Matrix series or a few episodes of The Twilight Zone should be able to guess Wire’s big revelation. However, it is fascinating to watch how Fassbinder systematically subverts Stiller’s reality without the benefit of Twenty-First Century CGI. Largely eschewing even the special effect of their era, Fassbinder and his old school design team create a convincing hierarchy of worlds. Indeed, this is decidedly Teutonic science fiction, set against the austere backdrop of Bauhaus architecture, filled with cold, reflective surfaces, throwing in an occasional Marlene Dietrich inspired musical number to keep things properly surreal.

Klaus Löwitsch, who somehow regularly appeared both on commercial West German television and in Fassbinder’s edgy art cinema, has the right rough-hewn everyman presence tempered with a flinty intelligence to hold viewer sympathies and attention throughout Wire. Though some chew the near-futuristic scenery a bit excessively, most members of Wire’s ensemble cast have a good genre look, such as Kurt Raab as Stiller’s serpentine rival, Mark Holm. Though his character is not long for the ostensive world, Ivan Desny is particularly effective establishing the film/series’ themes as poor ill-fated Lause.

Klaus Löwitsch, who somehow regularly appeared both on commercial West German television and in Fassbinder’s edgy art cinema, has the right rough-hewn everyman presence tempered with a flinty intelligence to hold viewer sympathies and attention throughout Wire. Though some chew the near-futuristic scenery a bit excessively, most members of Wire’s ensemble cast have a good genre look, such as Kurt Raab as Stiller’s serpentine rival, Mark Holm. Though his character is not long for the ostensive world, Ivan Desny is particularly effective establishing the film/series’ themes as poor ill-fated Lause.

Unlike some of Fassbinder’s more notorious films, Wire is hardly sexually provocative. Of course, as a product of Euro TV, there is a flash of nudity here and there. Instead of titillating though, Wire is out to bend minds. Aside from a clichéd anti-corporate subplot that frankly does not make much dramatic sense given the context of its wider conflicts, Wire is very well conceived, with an internal logic that holds together quite consistently.

In a way, the degree to which Wire’s successors have permeated fanboy culture today is a testament to how far ahead of the curve it was in 1973. Ironically, Daniel F. Galouye’s original source novel was remade as The Thirteenth Floor, released in 1999, only to be utterly overshadowed by the thematically related Matrix. Though their merits are radically different, the cool and sleek Wire totally holds its own as ambitiously brainy sci-fi when compared to the Wachowskis’ initial blockbuster. Definitely recommended for those looking for a retro-futuristic mind-trip, Wire opens this Friday (7/22) at the IFC Center.

Posted on July 21st, 2011 at 9:23am.

This looks great! I’ve never seen a Fassbinder film but I’m willing to break the ice to go see this.