By David Ross. Let’s admit it. We all have a weak spot for certain women from the wrong side of the political tracks. Maybe you have little fantasies about discussing Bresson with Susan Sontag while soaping her back in the tub. Maybe you imagine sharing the Sunday paper with Joan Didion. My own weakness – lifelong – is for Patti Smith. I had a girlfriend who gamely stood in line to have Patti sign a CD copy of Horses for me. When she finally got to the front of the queue, she told Patti, “My boyfriend is in love with you.” Patti said, “Doesn’t he notice these grey hairs?” My girlfriend said, “I don’t think he cares.” Well spoken on my behalf.

William Blake offers – perhaps ‘records’ is the more appropriate verb – this exchange with the prophet Isaiah in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell:

Then I asked: “Does a firm persuasion that a thing is so, make it so?”

He replied, “All poets believe that it does, and in ages of imagination the firm persuasion removed mountains; but many are not capable of a firm persuasion of anything.” (V, 27-32).

What’s so alluring in the supra-physical sense is Patti’s capacity for this “firm persuasion.” She’s not mugging (like Bono) or merely howling (like Kurt Cobain): her music is a disciplined act of conviction in her own poetic and prophetic calling. One can look awfully silly as a self-styled poet or prophet (Jim Morrison certainly did) but Patti never waivers and never allows the spell to break; we’re convinced in the end because she’s utterly convinced from the start. Arguably, Patti was the last legitimate keeper of the romantic flame itself, that desperate belief in art that began in the late nineteenth century and guttered utterly in our own time.

A bony, boyish waif from Woodbury Gardens, NJ, Smith cut her teeth at the Chelsea Hotel and St. Mark’s Church during the late 1960s and early 1970s, achieving minor underground celebrity as an actress, playwright, rock journalist, artist, and poet. Her chief inspirations were predictable but nonetheless powerful: Rimbaud, Genet, Burroughs, Ginsberg, Dylan, Hendrix, the Rolling Stones. In 1971, she began to recite her poetry to guitarist Lenny Kaye’s accompaniment. By 1976, she had improbably become the most acclaimed female rock star since Janis Joplin and Grace Slick had emerged ten years earlier.

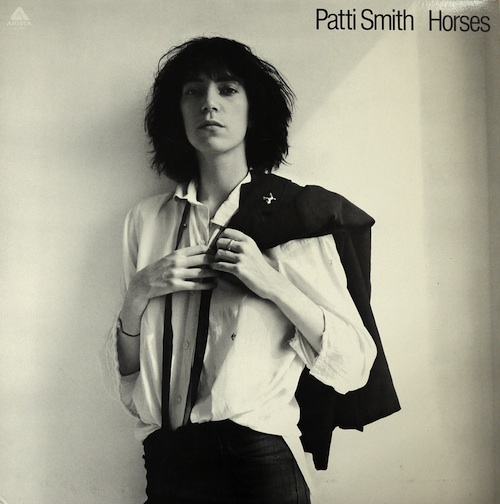

Smith’s first album, Horses (1975), weds cascades of Beat-and Symbolist-inflected poetry to the lean, driving sound of proto-punk garage rock. The album remains a signature argument for the artistry of rock’n’roll and is to my mind one of the ten supreme albums of the rock era. Rolling Stone ranks Horses 44th on its list of the 500 greatest albums of all time, just behind Dark Side of the Moon. This becomes a backhanded compliment when you consider certain albums that rank higher: the Eagles’ Hotel California (#37), Carol King’s Tapestry (#36), David Bowie’s The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (#35), U2’s The Joshua Tree (#26), Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours (#25), and Michael Jackson’s Thriller (#20). Preferring Tapestry to Horses is like preferring Jennifer Aniston to Veronica Lake – an aesthetic misjudgment that raises questions about one’s entire world view.

Smith’s first album, Horses (1975), weds cascades of Beat-and Symbolist-inflected poetry to the lean, driving sound of proto-punk garage rock. The album remains a signature argument for the artistry of rock’n’roll and is to my mind one of the ten supreme albums of the rock era. Rolling Stone ranks Horses 44th on its list of the 500 greatest albums of all time, just behind Dark Side of the Moon. This becomes a backhanded compliment when you consider certain albums that rank higher: the Eagles’ Hotel California (#37), Carol King’s Tapestry (#36), David Bowie’s The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (#35), U2’s The Joshua Tree (#26), Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours (#25), and Michael Jackson’s Thriller (#20). Preferring Tapestry to Horses is like preferring Jennifer Aniston to Veronica Lake – an aesthetic misjudgment that raises questions about one’s entire world view.

Judge for yourself: here is the epic studio version of “Birdland,” Smith’s fantastic synthesis of Arthur C. Clarke, Shelley’s Queen Mab, and the Book of Revelations. Ponder also these scruffy, raging, nearly epileptic live versions of “Horses” and “Gloria.”

After releasing three further albums of somewhat waning merit, Smith married guitarist Fred “Sonic” Smith, of the defunct proto-punk band MC5, and retired to suburban Detroit to raise a family. Patti and Cat Stevens, as far as I know, are the only stars ever to turn their backs on their own stardom and fade into voluntary privacy (in Cat’s case, good riddance). Following Fred’s death in 1994, Smith returned to recording and – mirabile dictu, as her Rimbaud would say – she staged the most thorough and improbable comeback in the history of rock, releasing five albums of vintage intensity between 1996 and 2007. Her AARP years turned out to be high ART years.

Yet further surprises were in store. In 2010, she published the first volume of her memoirs, Just Kids, which won, of all things, the National Book Award, and is now being prepped as a film. The book narrates her Bohemian beginnings amid the downtown art scene of the late sixties and her profound bond (romantic, sexual, artistic, fraternal) with Robert Mapplethorpe. The photographer took to Times Square hustling and gay S&M on Patti’s romantic watch, which only begins to get at the strange turns that their lifelong friendship managed to endure. The book is supposed to be an epic love story, but the problem is that the manic, self-absorbed, perpetually high Mapplethorpe doesn’t come across as particularly loveable, giving the whole book an arbitrary air. My sympathy finally snapped after reading that he stole an original William Blake print from Brentano’s and then, panicking at the possibility that some Sherlock Holmes would figure things out, tore it to shreds and flushed it down a toilet. As an artifact of the development of the human spirit, that Blake print was infinitely more valuable than Mapplethorpe’s entire oeuvre. There must be rungs of hell reserved for depraved little shits of his sort.

Just Friends is a compelling document because Patti is a fascinating person and because her entire adult life has cleaved the dead center of the American avant-garde. And yet the book is short on literary prowess. Patti is genuinely hardwired for a certain kind of free-form poetry – possesses the strange associative and dissociative cross-circuitry – but she has no instinct for sequential narrative or evocative prose. She’s no Nabokov or Virginia Woolf. For that matter, she’s no Jim Carroll, a former boyfriend whose Basketball Diaries is the informing literary model.

The book is filled with incredible sinkholes of collapsed literary competence, of which this may be the most egregious example:

It was exciting just to stand in front of the hallowed ground of [. . .] the Five Spot on St. Mark’s Place where Billie Holiday used to sing, where Eric Dolphy and Ornette Coleman opened the field of jazz like human can openers. (48)

Patti is equally capable of appalling barbarities like: “My Keith Richards haircut was a real discourse magnet.” And: “[Gregory Corso] would always spell trouble and might even wreak havoc, yet he gave us a body of work pure as a newborn fawn.” On the other hand, she occasionally turns a good anecdote, as when recollecting her first encounter with Allen Ginsberg. The Beat patriarch materialized after she’d run out of coins at an automat:

Allen added the extra dime and also stood me to a cup of coffee. I wordlessly followed him to his table, and then plowed into the sandwich.

Allen introduced himself. He was talking about Walt Whitman and I mentioned I was raised near Camden, where Whitman was buried, when he leaned forward and looked at me intently. “Are you a girl?” he asked.

“Yeah,” I said. “Is that a problem?”

He just laughed. “I’m sorry. I took you for a very pretty boy.”

I got the picture immediately.

“Well, does this mean I return the sandwich?”

“No, enjoy it. It was my mistake.” (123)

In the grand scheme of her career, however, Patti’s foibles as a formal writer are incidental. A single refulgent moment of genius atones for fifty bad novels (George Sand) or forty years of aimless pop grinning (Paul McCartney). A smattering of literary boners is nothing in the Great Ledger of Art. Listening to Horses, we rightly shut up about it.

Posted on September 7th, 2011 at 10:16am.

David, that piece is simply badass. It’s bold, funny, sincere, and — almost most importantly — has a very deft streak of smartass in it.

My weak spot for women on the wrong side of the political track showed itself mostly in college. Famous lioberal women today aren’t really free-thinkers, but rather collectivist dupes … so sad.

It was a pleasure to read that, David.

Jesus, David. Isn’t it possible to praise your favorite artists without bashing others?