If you’re still following this series, here is the new international trailer for The Chronicles of Narnia: Voyage of the Dawn Treader. This one’s a bit more elaborate than the first trailer, so take a look …

Posted on October 11th, 2010 at 1:01pm.

If you’re still following this series, here is the new international trailer for The Chronicles of Narnia: Voyage of the Dawn Treader. This one’s a bit more elaborate than the first trailer, so take a look …

Posted on October 11th, 2010 at 1:01pm.

By Joe Bendel. To be fair, the evangelical film industry here in America is still in its infancy, but it would behoove Christian filmmakers to look to Finland for inspiration. Submitted last year as the Scandinavian country’s official foreign language Oscar contender, themes of Christian faith and redemption are front and center in Klaus Hӓrö’s Letters to Father Jacob, which opened this Friday in New York. [See the trailer here.]

As Letters begins, one might think it’s a film noir. About to be released on a pardon she never requested, the hardboiled Leila Sten does not want anyone’s help. Yet as the dramatically lit prison official explains, a compassionate retired priest has offered her a job helping with his correspondence. Blind but profoundly devout, Father Jacob receives letters asking for his prayers from spiritually ailing people around the country. At least, he does until Leila arrives.

Naturally, his simple piety and do-gooder mentality initially irk the callous Leila, even though the depth of his faith and commitment are unimpeachable. The film builds towards a redemptive crescendo of reconciliation, but director Hӓrö never engages in cheap theatrics along the way. Instead, Leila’s gradual change of heart culminates in a relatively quiet, but truly honest pay-off.

As the title Father, Heikki Nousiainen truly transcends the shopworn kindly old country priest stereotypes with a performance of genuine pathos and humanity. Though it is a less showy role, Kaarina Hazard is quite accomplished as the surly Sten, deftly delivering the film’s emotional knockout punch. Indeed, they both have the look of real flesh-and-blood people who have seen a lot of life’s pain and struggles.

Like recent evangelical films, Letters is a deeply religious work – yet as cinema, it is fundamentally character driven. It is also not afraid to look into the darkness and doubts lingering in its characters’ souls. Hӓrö helms with a sensitive touch throughout, exhibiting tremendous sympathy for the polar opposite protagonists. A handsome production, Tuomo Hutri’s warm cinematography strikingly captures the verdant surrounding environment while Kaisa Mӓkinen’s sets look dank yet appropriately sheltering.

Deceptively simple, Letters is a subtly powerful film. Elegantly crafted and legitimately moving, it is definitely recommended to all art-house cinema patrons not already too cynical to appreciate its sincerity. It is now playing in New York at the Cinema Village, and will expand to Los Angeles this week.

Posted on October 11th, 2010 at 11:45am.

[Dr. Li-ling Hsiao, a longtime friend of Libertas, is Associate Professor and Assistant Chair of the Department of Asian Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. This article appears in the 2010 issue of the Southeast Review of Asian Studies.]

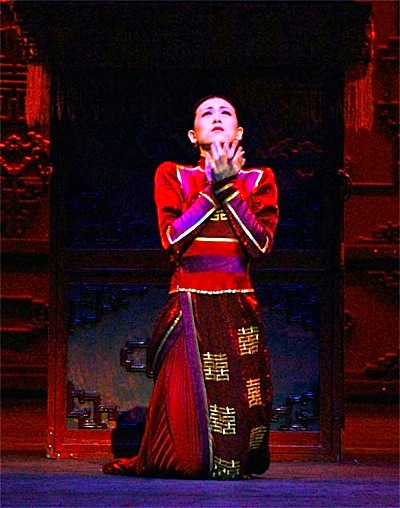

By Dr. Li-ling Hsiao. On a dimly lit stage, an old man lifts a cane and lights the red lanterns. Accompanied by the spare sound of ringing bells, the lanterns gradually rise like an ascending curtain and reveal a stage space for the dance of red lanterns performed by a corps de ballet dressed in blue. A female voice, singing in the style of the Peking opera, gradually becomes audible. This prelude opens Dahong denglong gaogao gua or, as it is better known in the West, Raise the Red Lantern. The performance combines elements of ballet, modern dance, and Peking opera. The conflation of East and West governs every creative aspect of the ballet, which explains why it has been acclaimed equally in China and throughout the world.

The ballet is the brainchild of Zhang Yimou (b. 1951), who made his name in the West as the director of the renowned Chinese film Raise the Red Lantern (1991). Zhang won the best director award at the Venice International Film Festival in 1991, and the film received an Academy Award nomination as best foreign film in 1992. Subsequent films like Shanghai Triad (1995), Hero (2002), House of Flying Daggers (2004), and Curse of the Golden Flower (2005) sealed Zhang’s reputation as a giant of world cinema, while his direction of the extravagant opening ceremony of the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing made him an international celebrity. Given his penchant for stunning visual pattern, Zhang’s interest in the highly stylized media of opera and ballet is hardly surprising. The ballet – his first – premiered in Beijing in 2001 and has since played in Europe and America. A revised version of the ballet, featuring the National Ballet of China, with music by Chen Qigang and choreography by Wang Xinpeng and Wang Yuanyuan, appeared on video in 2005, encouraging an assessment of what Zhang has both achieved and failed to achieve.

The ballet is the brainchild of Zhang Yimou (b. 1951), who made his name in the West as the director of the renowned Chinese film Raise the Red Lantern (1991). Zhang won the best director award at the Venice International Film Festival in 1991, and the film received an Academy Award nomination as best foreign film in 1992. Subsequent films like Shanghai Triad (1995), Hero (2002), House of Flying Daggers (2004), and Curse of the Golden Flower (2005) sealed Zhang’s reputation as a giant of world cinema, while his direction of the extravagant opening ceremony of the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing made him an international celebrity. Given his penchant for stunning visual pattern, Zhang’s interest in the highly stylized media of opera and ballet is hardly surprising. The ballet – his first – premiered in Beijing in 2001 and has since played in Europe and America. A revised version of the ballet, featuring the National Ballet of China, with music by Chen Qigang and choreography by Wang Xinpeng and Wang Yuanyuan, appeared on video in 2005, encouraging an assessment of what Zhang has both achieved and failed to achieve.

The story of the Red Lantern originates in a novella titled Wife and Concubines by Su Tong (b. 1963) published in 1990. Su Tong’s novella tells the story of a nineteen-year-old college student, Songlian, who marries into a rich household and becomes the fourth concubine of the much older master. The novella centers on the vicious competition and relentless jealousy governing the household world of the wives, concubines and maids, and on the friendship that develops between Songlian and the elder son of the master, Feipu, which verges on transgression. As these two plot lines progress, Songlian increasingly withdraws into solitude and self-confinement, while the abandoned well in which several concubines have died looms threateningly outside her room. Her attempt to distance herself from the intrigues of the household, however, does not prevent her from striking back after being slandered, resulting in the death of her maid and the loss of her master’s favor. After witnessing the adulterous third wife’s death by drowning in the well, Songlian loses her mind and becomes an invalid inmate of the household.

Zhang Yimou’s film brings a stunning visual aestheticism to Su’s story, while engaging in a significant plot revision. In the novella, Songlian attempts to remain above the petty intrigues of the household, but in the film she quickly succumbs to something devious and dark in her own nature and becomes as fully Machiavellian as the other women. The film thus assumes a moral and dramatic weight missing from the novella: Zhang’s Songlian is no mere innocent victim of circumstance, but a complex moral agent whose downfall is largely her own doing. In both novella and film, Songlian is the unintentional victimizer of the maid, but in the film she is the effective murderer of the third wife, whose infidelity she reports to the treacherous second wife, knowing, in some recess of her mind, that her tale is the death warrant of a competitor. Significantly, the novella envisions Songlian crazed by circumstance, while the film envisions her crazed by guilt. Zhang thus reconceives the story as a parable of the self caught in the fate it has created, and the film becomes a Shakespearean tragedy played out in a Chinese social context. The ingénue of the novella is no more; she has been replaced by the tragic heroine.

Zhang also accentuates the story’s symbolic elements, bringing a new complexity and intensity to the story. Most significantly, the film elevates the lantern, which the novella mentions only peripherally as a crucial leitmotif. In Zhang’s film, the lantern hangs in the courtyard of the lady with whom the master intends to spend the night. Fantasizing about being a wife or concubine, the maid, Yaner, raises her own red lantern, which provides Songlian with an excuse to mete out harsh punishment and unleash her own frustrations. She forces Yaner to kneel in the courtyard until the maid dies in the snow. Thus, the red lantern, an auspicious symbol, becomes a symbol of illicit desire and ambition as well as a morally ambiguous marker of the master’s favor. Zhang also makes an important symbol of the small hammers used to massage the feet of the wives and concubines. The massage, like the lantern, is a symbol of privilege, and the clicking sound of the hammer echoes throughout both the household and film, indicating the constant competition for favor. The sound of the hammer likewise has erotic connotations, suggesting the physical ministrations enjoyed by some but denied to others. Zhang brilliantly utilizes the symbolic elements to underscore the silent drama that plays out within the household; the symbolism allows Zhang to explore the intricacies of his domestic drama without impinging on the silence and the isolation that is its subtext. Finally, Zhang shifts symbolic emphasis from the well (a crucial motif of the novella) to a small stone room on the roof of the compound. Both symbolize the tragic fate of unfaithful women, but the room, situated above, suggests a totalitarian world of observation and control, and represents the panoptic eye of the master and his minions. Zhang achieves this effect by frequently adopting a rooftop perspective on the action below, taking in the stone room in what seems an incidental fashion. Visually, Zhang implants the room as a subconscious consideration and thereby prepares for its powerful revelation as a place of execution when the third wife is carried there, as if in funeral procession, at the end of the film. Zhang thus makes clever use of his actual location, the Qiao Compound in Pingyang, Shanxi Province, and turns an accidental feature of the structure – perhaps a harmless storage shed or recreational pavilion – into a haunting symbol of power and the dread of power.

Zhang also accentuates the story’s symbolic elements, bringing a new complexity and intensity to the story. Most significantly, the film elevates the lantern, which the novella mentions only peripherally as a crucial leitmotif. In Zhang’s film, the lantern hangs in the courtyard of the lady with whom the master intends to spend the night. Fantasizing about being a wife or concubine, the maid, Yaner, raises her own red lantern, which provides Songlian with an excuse to mete out harsh punishment and unleash her own frustrations. She forces Yaner to kneel in the courtyard until the maid dies in the snow. Thus, the red lantern, an auspicious symbol, becomes a symbol of illicit desire and ambition as well as a morally ambiguous marker of the master’s favor. Zhang also makes an important symbol of the small hammers used to massage the feet of the wives and concubines. The massage, like the lantern, is a symbol of privilege, and the clicking sound of the hammer echoes throughout both the household and film, indicating the constant competition for favor. The sound of the hammer likewise has erotic connotations, suggesting the physical ministrations enjoyed by some but denied to others. Zhang brilliantly utilizes the symbolic elements to underscore the silent drama that plays out within the household; the symbolism allows Zhang to explore the intricacies of his domestic drama without impinging on the silence and the isolation that is its subtext. Finally, Zhang shifts symbolic emphasis from the well (a crucial motif of the novella) to a small stone room on the roof of the compound. Both symbolize the tragic fate of unfaithful women, but the room, situated above, suggests a totalitarian world of observation and control, and represents the panoptic eye of the master and his minions. Zhang achieves this effect by frequently adopting a rooftop perspective on the action below, taking in the stone room in what seems an incidental fashion. Visually, Zhang implants the room as a subconscious consideration and thereby prepares for its powerful revelation as a place of execution when the third wife is carried there, as if in funeral procession, at the end of the film. Zhang thus makes clever use of his actual location, the Qiao Compound in Pingyang, Shanxi Province, and turns an accidental feature of the structure – perhaps a harmless storage shed or recreational pavilion – into a haunting symbol of power and the dread of power.

Continue reading Dancing the Red Lantern: Zhang Yimou’s Fusion of Western Ballet and Peking Opera

By David Ross. Morgan Neville’s The Cool School (2008) is a propulsive, loose-lipped documentary about the birth of an indigenous modern art movement in Los Angeles. It tells the story of painters, ceramicists, and assemblage artists whose hub was Walter Hopps and Irving Blum’s Ferus Gallery at 736a N. La Cienega.

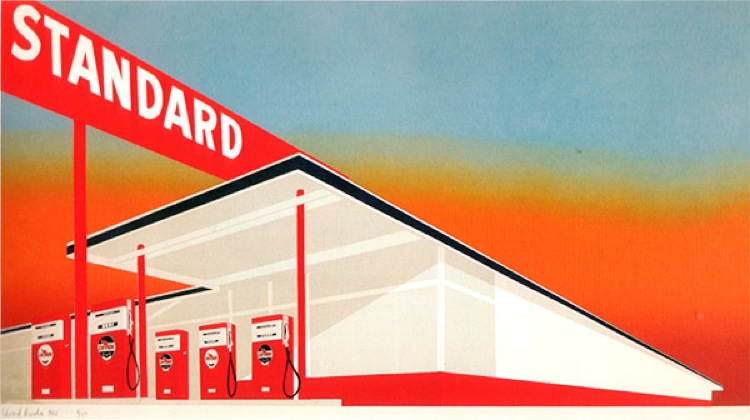

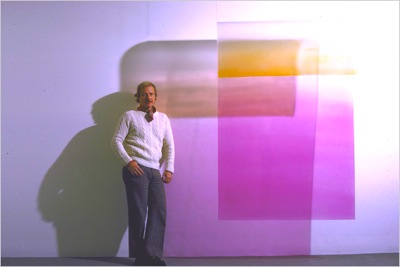

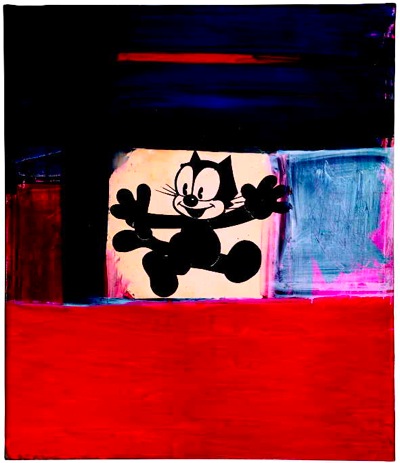

These artists – John Altoon, Larry Bell, Billy Al Bengston, Wallace Berman, Robert Irwin, Craig Kauffman, Ed Kienholz, Ed Moses, and Ken Price – may be unknown to the uninitiated, but Frank Gehry and Ed Ruscha, who moved at the periphery of the group, give the idea. Between the mid-1950s and mid-1960s, these artists led the West Coast transition from the astringency of abstract expressionism to the affectless exclamation of pop and postmodern art, and created from scratch an aesthetic and cultural posture to rival the pomp and self-importance of New York. Their inspirations were local and various: the custom car culture, the surf culture, urban detritus, plastic, glass, signage, the bright sharp aspect of the sunshine and the sand and water, the Pacific light itself. The prevailing spirit was macho, competitive, and hard-living in the Pollock vein, with women present “to service the men” and suffering the usual collateral damage. By the late-1960s, the gallery was hawking the work of New Yorkers like Lichtenstein, Johns, Stella, and Warhol, and the local scene broke up amid long repressed mutual annoyance. Hopps sold out to Blum and Blum moved New York, while the Ferus artists went on to early deaths and/or a degree of fame.

The Cool School artists played out “all of the Los Angeles prejudices,” says Shirley Neilsen Blum, a PhD. in art history who left Hopps to marry Blum.

“They were very involved with the beach and with the surf and with the road and with automobile and with the girls and with the local tavern [Barney’s Beanery]. That’s what they did. They had a lot of spare time. But the studio was a very different place. When they got into the studio, they were alone. And they were all born with the legacy of modernism. In other words you didn’t look at the external world for your subject. The subject came from you … Los Angeles is the city of light and air and reflection and scintillation of surface. They began to play with qualities of perception. Instead of what the impressionists tried to do, which was to see the effect of color on light, light itself became a palpable experience of the object itself.”

The Cool School is interested in social history rather than aesthetic analysis and doesn’t have much to say about the art itself. I would have preferred more lingering reflection on the images and somewhat less gossip and reminiscence. Postmodern art of the surface – superficiality in the literal sense – is the kind of thing I’m inclined to beat with a stick, but I have a hard time mustering my usual ire. While Warhol and Lichtenstein trafficked in crowd-pleasing irony, the artists of the Cool School were at least emotionally sincere, and their emphasis was for the most part aesthetic: they were interested less in social and political commentary than in image, reflecting their origins in abstract expressionism. None of this art seems to me particularly profound, but I can’t say that it’s entirely wrongheaded. Ruscha, the shrewdest and most ingenious artist to emerge from the cool school milieu, largely traffics in ironic conceptual puzzles, but even in his case there’s a redeeming subtlety and sense of humor and refinement of execution that distinguishes him from Warhol. He reminds me, in fact, of Saul Steinberg, another ingenious visualizer of what words mean and a particular hero of mine.

Ignoring its merely sidelong glance at the art, The Cool School is impeccable as documentary craft. Nearly all of the key figures – happily, an unguarded bunch – contribute their recollections and grind their axes, and the film pops with color and sound: vintage footage on the one-hand and a sublime soundtrack of jazz, surf music, and punk on the other. Whatever one thinks of the art – and there’s plenty of reason to be skeptical – nobody is likely to fall asleep.

The film complains that the L.A. art scene was co-opted by glamor-seeking know-nothings from the moneyed world of film. Ironically, then, it taps Jeff Bridges as narrator and indulges Dennis Hopper and Dean Stockwell as a spacey, possibly stoned chorus. Hopper was a major collector of contemporary art, as we all know, but all the same I would have preferred less from posturing actors and more from historians in a position to assess the Cool School and give a larger sense of what it was up to. What’s lacking is any sense of responsible external opinion.

Ruscha, by the way, is making his entire catalogue raisonné available online. As far as I know, this is an unprecedented experiment in public access and self-canonization. See here.

For more Libertas coverage of fine art, see here, here, here, and here.

Posted on October 10th, 2010 at 11:08am.

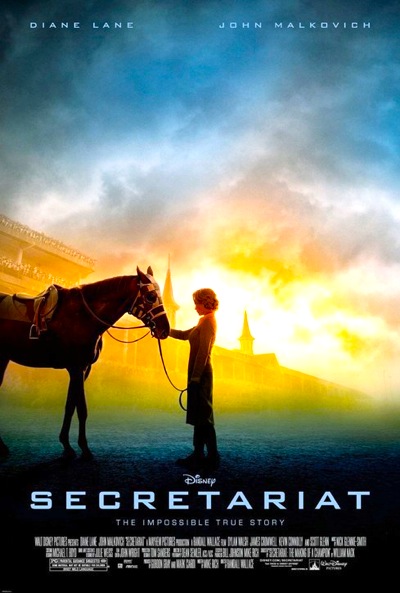

By Jason Apuzzo. When I was in high school, some of my football buddies and I would trek over to Hollywood Park here in Los Angeles on weekends to watch horse races. My friends went to gamble; I never bet a dime. I went for the spectacle, and most of all for the supernal beauty and intensity of the horses themselves. There was something so pure and lovely about them; at the same time, look into the eyes of any racehorse and you will see a kind of wild, daemonic energy that you don’t always see in other animals – something both divine and furious that propels them down the track. And although I haven’t really followed horse racing or horses in a long time, I was reminded of all that watching Randall Wallace’s superb new film, Secretariat – one of the better live-action films I’ve seen from Disney in years.

By Jason Apuzzo. When I was in high school, some of my football buddies and I would trek over to Hollywood Park here in Los Angeles on weekends to watch horse races. My friends went to gamble; I never bet a dime. I went for the spectacle, and most of all for the supernal beauty and intensity of the horses themselves. There was something so pure and lovely about them; at the same time, look into the eyes of any racehorse and you will see a kind of wild, daemonic energy that you don’t always see in other animals – something both divine and furious that propels them down the track. And although I haven’t really followed horse racing or horses in a long time, I was reminded of all that watching Randall Wallace’s superb new film, Secretariat – one of the better live-action films I’ve seen from Disney in years.

Truth be told, Secretariat really isn’t so much about the legendary race horse that electrified the sports world in 1973. Wallace and screenwriter Mike Rich realized, smartly, that the phenomenal thoroughbred (nicknamed ‘Big Red’) who still owns the track records at two of the three Triple Crown races – the Kentucky Derby, and the Belmont Stakes – is too legendary, too awesome a figure to center the story around. Almost forty years after the horse’s greatest triumphs, rooting for Secretariat is a bit like rooting for a hurricane – you already know the outcome. And so Wallace and Rich smartly shifted the story of Secretariat to where it quite clearly needed to be: with the horse’s fiesty, headstrong owner Penny Chenery, played in this film with style and intensity by Diane Lane. Secretariat is essentially Penny Chenery’s story – and, as we learn in ways both subtle and overt, her story is really America’s.

As Secretariat opens, we’re introduced to housewife Penny Chenery and her pleasant, unassuming family in what appears to be a middle-class, WASPish burg of Colorado. A sudden tragedy in the family sends her to Virginia, where she’s forced to take over the family horse ranch. Chenery does a little research, and discovers that the lineage of one of the foals in her care may portend something special – although the horse racing professionals around her, as well as her family, all doubt it. At a coin toss between Chenery and legendary racing owner Ogden Phipps over Secretariat’s fate, Phipps wins the coin toss – and picks another horse for himself, leaving young Secretariat to a suddenly very happy Chenery. And history, as they say, was made.

Chenery puts Secretariat in the hands of French-Canadian trainer Lucien Laurin, played here with warmth and (predictably) eccentric humor by John Malkovich. It’s nice to see Malkovich play something other than a freak, frankly – I wasn’t sure he could still do it. His performance brings a dash of life and sophistication to the proceedings. We follow Laurin and Chenery as they train the horse and prep it for its first big race at the Aqueduct Racetrack in New York. I don’t want to give anything away here, but let’s just say that Secretariat’s first big race doesn’t exactly go as planned; both Laurin and Chenery realize that they’ve been following the wrong strategy – they’ve been too cautious – with their curiously slow-starting, almost lazy horse.

Secretariat, you see, is a bit of a show-off, who likes to start his races slow – at a casual pace – typically beginning each race at the back of the pack … only to come charging in late and finish strong. This, we learn, is part of the dual miracle that Secretariat represented: not only did the horse shatter records, but he typically ran like he was asleep for the first half of any race. And, indeed, even when he finished races in record time he was typically still accelerating at the finish. Another way of putting it is that the horse Secretariat was a bit of a gambler, much like his owner – and difficult to train.

Secretariat’s ability to live up to his full potential becomes a huge issue for Penny Chenery because when her long-ill father (played by Scott Glenn) finally passes away, the estate taxes on his ranch amount to $7 million – and Chenery is suddenly in the awful position of having to either sell her beloved Secretariat, or gamble everything her family owns on the horse. In essence, the horse has to win The Triple Crown – or at a minimum The Kentucky Derby – or her family could be ruined.

The easy decision for Penny Chenery at this point would have been to sell the horse. It’s not the choice she makes, however. And let’s pause for a moment and dwell on this point.

As some of you may be aware, Secretariat has improbably become a ‘controversial’ film in recent days – largely due to the fact that Salon’s Andrew O’Hehir (hostile over the fact that Randall Wallace has been promoting Secretariat to Christian audiences) went off his meds recently and called the film (among other things) “a work of creepy, half-hilarious master-race propaganda almost worthy of Leni Riefenstahl … a quasi-inspirational fantasia of American whiteness and power.”

O’Hehir’s toxic and abusive ramblings aside, it doesn’t surprise me that progressive critics of his ilk would react badly to Secretariat, as the film’s real purpose – it’s ‘agenda,’ as we say nowadays – seems to be the valorizing of a certain kind of stubborn, resourceful, tight-lipped Yankee/WASP woman (the type of woman Katherine Hepburn and Joan Crawford and Bette Davis built their careers on) that appears to have faded away in our current age of ‘resentment,’ as Harold Bloom likes to call it. If Secretariat is anything, it’s a love letter to that particular kind of woman from America’s past – and, hopefully, America’s future.

Our ‘resentful,’ politicized era – the era of Lady Gaga and Lisbeth Salander – no longer seems interested in women like Penny Chenery, i.e. classy, stiff-upper-lip-type dames in smart business suits with perfectly coiffed hair who get their way through moxie and determination. For various reasons we’ve told ourselves that we don’t need these kind of women anymore, especially on-screen, because we’ve ‘advanced’ into a Brave New World where women get their way through some combination of: a) harpie-like political agitation; b) screwing men blind, after they’re already pumped full of Viagra; c) narcissistic fugue-states, fueled by Facebook and reality TV, or; d) unloading a full machine gun clip at people they don’t like (Angelina Jolie/Milla Jovovitch/Kate Beckinsale, etc.).

It never seems to occur to people like O’Hehir – and there are a lot of them, particularly in the entertainment industry – that none of these represent valid options for most women, even if they’re sometimes fun to watch on-screen. Secretariat’s Penny Chenery is that old-school type of woman who dominated Hollywood cinema in the 1940s – and American life in the 1950s – who gets her way in life because she’s got steel in her spine, and is willing to take enormous risks even when the pusillanimous men around her (and there are a lot of them in this film) tell her not to.

So back to the film. As the stakes get higher for Chenery, people start to fall away. One of her daughters – the very blonde and very perky AJ Michalka – grows distant and starts to dabble in left-wing activism (admittedly, some of the scenes with Michalka are obviously played for laughs). More serious is that Chenery’s brother – and even her husband – abandon her at one point, consigning her to take all the financial risks associated with backing the horse. Ouch. [Why Chenery lets these stiff jerks so easily back into her life later on is never adequately explained, unfortunately – and this represents one of the weaker aspects of the film.] Everybody outside of the horse’s training staff starts to think she’s crazy – and in reality, of course, she is crazy. Most people would not wager their family’s future on a horse winning The Triple Crown. But as we all know, miracles do sometimes happen …

This is the point in the film where we hunker down at the track and really start to see the horses race – because these beautiful and fiery creatures really are miracles. And here the film truly comes to life . The two most significant races shown in the film – The Kentucky Derby, and The Belmont Stakes – play out with almost unbearable suspense, due to Secretariat’s cheeky unwillingness to start a race strong. So at the outset of the Kentucky Derby, Secretariat starts slow again – and Penny’s life dangles before her eyes and ours, and the trainer despairs and threatens to walk out – until … this glorious, powerful, and weirdly arrogant animal called Secretariat takes over and leaves the rest of the field in the dust, smashing Churchill Downs’ track record.

And of course, that’s only the first of Secretariat’s three great races that we see. I won’t spoil the other two for your, but The Belmont is really a whopper …

If I have a quibble with Secretariat, it would be about the racing sequences, however – which are suspenseful and well-paced, but which somehow lack the speed and the grandeur these events have in person. Something this film was crying out for was a large format like IMAX – in the old days, Cinerama would’ve been perfect – because there is something truly awe-inspiring about watching these fantastic animals, with their furious eyes and driving muscles, race wildly around the racetrack. Instead, what Randall Wallace does periodically is to intercut footage shot on consumer-level, high-def camcorders from the jockey’s perspective – and while this brings a certain frenetic intensity to the races, it somehow pulls the movie away from the mythic grandeur it deserves. I mean, this is Secretariat we’re supposed to be watching here – not your kid’s pet pony on YouTube. [By the way, in his retirement Secretariat would sire some 600 foals. No wonder he always looks like he’s smiling.]

That aside, the drama between Chenery and her family gradually subsides in the third act of the film – there are no really dramatic resolutions – in the wake of the awesome spectacle that Secretariat and his victories represented. What we’re left with is the notion that Penny Chenery’s stubborn faith in her horse was validated, far beyond what she or anyone else might have imagined. Basically, she was wildly impractical – crazy – but her persistence paid off. How perfectly American. Only four years before Secretariat’s triumphs, that same kind of craziness and dogged persistence had put American astronauts on the Moon.

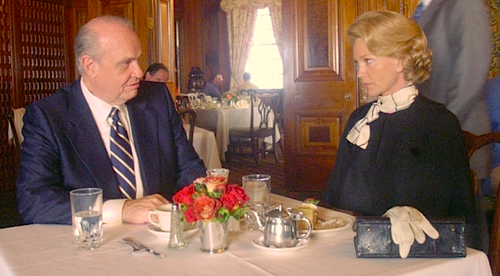

Diane Lane is sensitive, intelligent and strong as Penny Chenery. This is clearly her film, and she’ll likely get an Oscar nomination – although I admit that the film buff in me wonders what Bette Davis would’ve done with this same role. Wow. In any case, it was also great to see Fred Thompson appear briefly as owner ‘Bull’ Hancock. There should be a law requiring all films even tangentially dealing with the American South to feature Fred Thompson, and he should always have a name like ‘Bull’ or ‘Colonel’ or ‘Dutch’ or something like that. It’s good stuff.

I’m a little down on the film’s music, but veteran Aussie cinematographer Dean Semler (The Road Warrior) did a nice job on the film given Wallace’s visual strategy for it – and kudos to the production design team for recreating the early 1970s without lapsing into too much cliché. The costuming also is spot on, and Diane Lane’s suits and hair are almost stars of the film in their own right.

Beyond all that, I’d like to thank Wallace and Mike Rich for having the courage, and gentle good humor, to depict 60’s left-wing/hippie activism for what it so often (if not always) was – a rebellious regression on the part of young kids looking for their parents’ attention.

I doubt very much that Secretariat will become any sort of ‘hot-button’-type film, drawing controversy. The film is much too sentimental and warm-hearted for that, and Disney should expect the film to have a long lifespan as one of the better, ‘inspirational’ sports films. I also tend to think that the ‘Christian subtext’ of the film has been a bit overplayed in the media; beyond a few quotations of scripture, and a few hymns on the soundtrack, there isn’t really very much religious content in the film, at all – and no prosthelytizing of any kind.

Really what the film is about is one plucky, indomitable woman who took a big gamble – and about her stud of a horse, who ironically liked to gamble the same way. Everything paid off big for them both.

Posted on October 8th, 2010 at 8:11pm.

By Jennifer Baldwin. Guh. How could an episode in which the Lucky Strike catastrophe from last episode explodes in Roger’s face and SCDP is suddenly on the verge of collapse be so annoying and almost … boring? I blame Peggy and her useless storyline. I don’t think the writers of Mad Men are capable of writing a “bad” episode of the show, but this episode was one of my least favorite of the entire season.

I understand what Matthew Weiner is doing by showing Don repeat the same old insecure, emotionally closed-off, sleeping with every cute young thing that comes along pattern – it’s a way to show how hard it is for people to change and break out of their destructive behavior. I get it. But my lord, it’s getting boring! We all knew it was coming and then it did – Don and Megan the secretary did the horizontal mambo – but it was such a forgone conclusion that there was no drama there. I suppose we were all supposed to go, “Oh no! What about Faye?!” But really, who didn’t see this coming? Don seems incapable of making any lasting change for the better, and while that may be true to life, it makes for stagnant drama. I don’t mind Weiner exploring the idea that it takes a long time for people to mend their ways and break out of patterns of sin and bad behavior, but at some point he needs to transform this theme into something new. Don can’t be a man-whore forever.

I think this is why I’m slowly losing interest in Don as a main character and want the show to focus more on characters like Roger and Pete. In fact, the Roger storyline was probably my favorite of this episode, quickly followed by the Pete stuff (Peggy has gone back to annoying me again).

Roger is the spoiled rich kid who never grew up, but John Slattery’s acting and the writing’s snappy, quick-witted dialogue makes Roger a paradoxical character — charming rogue meets pathetic loser. Even as he behaves like an incompetent fool, he elicits a measure of sympathy. He breaks your heart even as he makes you shake your head. He doesn’t take things seriously, as Cooper pointed out, which is both his charm and his curse. That last troubling shot of Roger on the couch with Jane, those copies of “Sterling’s Gold” — his ridiculous and unintentionally hilarious memoir – resting like millstones on the coffee table, all point to a Roger who might not be long for this world. And I don’t mean a heart attack. Cabs of New York, beware of falling objects.

Pete is also a fascinating character, one who has gone from almost the villain of the show to one of its unsung heroes. He’s a much more interesting “youth” character than Peggy, she of the boundless creativity and plucky spirit (and for the moment, great sex life). Gah, she annoys me! Pete, however, is often morose and whiny. He’s spoiled in a way similar to Roger, and yet he’s a hard worker, he’s someone who wants to get ahead. He has ambitions and a strange sort of prescience about where the culture is headed. He’s both a misfit and a man yearning to fit in, and his struggle to reconcile the two makes for a compelling character arc.

I found his struggle this episode between family obligations and work to be much more interesting than Don’s turmoil over the loss of Lucky Strike and his strained relationship with Faye. Don’s story seemed like a rehash, whereas Pete’s had the feeling that something was truly at stake. He’s at the point in his life where he needs to make the decision between family and work, between security and ambition. Don has already “lost” his family; all he has is ambition. Pete, however, faces a real choice. And frankly, I’m torn on his behalf as well. I love innovative, forward-thinking, misfit Pete. But I also believe that family and personal relationships, ultimately, are more important than worldly success. Pete, for his part, seems as ambivalent about his choices as I am.

Some other thoughts:

• I cheered when Faye stood up for her ethics and rejected Don’s plea that she poach client information from other agencies and give it to him. I cried “NO!” when Faye gave in and offered Don the information about Heinz. Faye is much too good for Don. I wanted these two to work out, but now I think Faye needs to run far, far away. I worry that her actions will jeopardize her career. And all for what? For a man who sleeps with his secretary only a few hours after fighting with his girlfriend?

• Joan and Roger’s final embrace was a killer. She had no choice but to break things off completely with him – but my gosh, if I didn’t shed a tear for both of them. Many props to Christina Hendricks’ performance here. Their moment for happiness passed a long time ago, and there’s no way things could ever work out now, but it’s still sad to see. As much as I joke that Joan and Roger are my “one true pair,” I’m not sure they were every truly in love. Theirs is the tragic melancholy of two people who have realized at last that they should have been in love and now it’s too late.

• I chuckled at Jane in her artsy upscale apartment and Auntie Mame boho outfit, listening to classical music – the perfect picture of what she thinks makes a rich woman of culture. She’s such an empty poser! Roger has now lost two good women of taste – Mona and Joan – thanks to his own immaturity, and he’s stuck with vapid Jane.

• There’s absolutely no way we’ve seen the last of Ken’s fiancée and her family. A show doesn’t hire the great Ray Wise for a bit part with a couple of lines. The intriguing thing is what could possibly be so important about Ken’s future in-laws that they need to hire a recognizable name actor to play the father?

• FREDDY RUMSEN RETURNS!!! Alas, for one scene.

• I’ve never heard the phrase “Chinese Wall” before, so I had to Google it. Apparently it’s a business term having to do with information barriers and conflict of interests and so I guess it has relevance to Faye’s ethical dilemma over giving out client information to Don. I’m still disappointed Faye caved.

• Finally, something has got to be up with Megan. Her unconvincing speech about wanting to learn the advertising business and being an artistic person and blah, blah, blah Montreal left me questioning her motives. What’s her game? Is she going to try to bring Don and SCDP down with some kind of blackmail? Is she an operative of Teddy Chaough sent to destroy Don from within? Or is she just a Jane type, angling for a rich husband and life on easy street? Something is not right about the way she seduced Don. I fear nothing good can come from their fling on the couch. Only two episodes left to find out …

Posted on October 8th, 2010 at 9:07am.