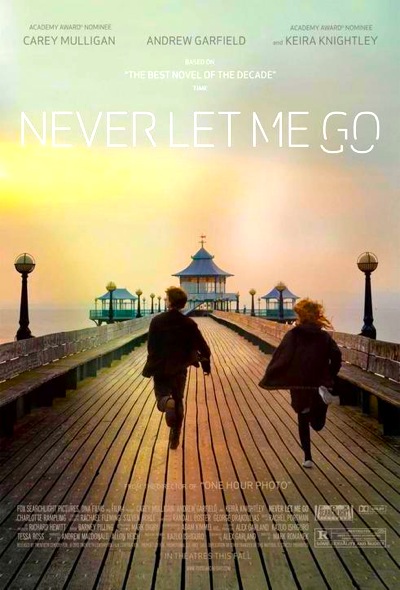

By Jason Apuzzo. I’m not sure we’re going to have time today to review director Mark Romanek’s new adaptation of Kazuo Ishiguro’s dystopian novel Never Let Me Go – which recently debuted in Toronto and opens in limited release nationwide today, starring Carey Mulligan, Keira Knightley and Andrew Garfield (the new Spider-Man) – so I thought I’d post an excerpt from Andrew O’Hehir’s interesting review over at Salon.

You could describe “Never Let Me Go” as set in an alternate-history version of postwar Britain, but as with all really good alternate histories, the changed universe really isn’t the point. Director Mark Romanek captures the slightly seedy and rundown reality of ’70s and ’80s British life in astonishing and even tragic detail; this is more like a period piece than a science-fiction movie. In fact, it resembles a Merchant-Ivory tragedy about doomed love in a war zone, except that the doomed love involves human guinea pigs and the war zone is not some tropic zone but the alleged good intentions of medical science.

There’s no way to write about “Never Let Me Go” without at least dropping hints about the ultimate destiny of Kathy (Carey Mulligan), Tommy (Andrew Garfield) and Ruth (Keira Knightley), the romantic triangle who meet as children in a dreary, peculiar boarding school called Hailsham House. If you don’t want to know any more about that, stop reading now. This is really never a secret in the film, although it’s concealed at first under a mask of horrifying euphemism — as an adult, Kathy becomes a “carer,” who works with “donors” until they reach “completion” — and I had read Ishiguro’s unforgettable novel and knew what was coming. Still, there’s a scene about 20 minutes into the movie when a sympathetic teacher named Miss Lucy (Sally Hawkins) finally spells out what the Hailsham children need to know about their future if they’re to have “decent lives,” as she puts it, and Romanek dramatizes this hammer-blow, life-changing moment with such power that I don’t want to undermine it.

Screenwriter Alex Garland, who is himself a novelist, sticks close to both the letter and spirit of Ishiguro’s novel; this movie is a veritable clinic in precise literary adaptation. He incorporates snatches of dialogue and even voiceover (read by Mulligan) straight from the book, without swamping the human drama or overwhelming Romanek’s astonishing visual evocation of a bygone Britain. His innovations are limited, but they help set the stage in important ways: The big medical breakthrough came in 1952, we are told in an opening title, and by 1967 life expectancy exceeded 100 years. This came at a price, of course, and “Never Let Me Go” asks us to consider that price in all its dimensions.

Kathy H., played by Mulligan as an adult and Isobel Meikle-Small as a child, has no last name. Neither do the other girls and boys at Hailsham (and it turns out, at other and even more dismal places). They won’t be needing them. Kathy is a tender, slightly dowdy girl with an off-kilter haircut and a yearning expression who develops a fatal early crush on Tommy (Charlie Rowe, as a child), a hot-tempered outcast who is tormented by other boys. Kathy’s best friend, Ruth (Ella Purnell, as a child), a popular and elegant girl, mocks Tommy at first — until she corners him, kisses him and claims him as her own.

Kathy H., played by Mulligan as an adult and Isobel Meikle-Small as a child, has no last name. Neither do the other girls and boys at Hailsham (and it turns out, at other and even more dismal places). They won’t be needing them. Kathy is a tender, slightly dowdy girl with an off-kilter haircut and a yearning expression who develops a fatal early crush on Tommy (Charlie Rowe, as a child), a hot-tempered outcast who is tormented by other boys. Kathy’s best friend, Ruth (Ella Purnell, as a child), a popular and elegant girl, mocks Tommy at first — until she corners him, kisses him and claims him as her own.

It’s an act of ordinary schoolgirl predation, one that could happen anywhere at any time. But it carries more weight in the isolated hothouse atmosphere of Hailsham, where the kids rarely encounter outsiders and sit around play-acting at ordering tea in a restaurant — something they may or may not ever get to do. Or at least it seems to carry more weight. One of the questions Kathy asks herself as she, Ruth and Tommy grow apart and then reunite, very near the end of their journey, is whether their artificially foreshortened lives are really much different than anyone else’s.

Romanek does so many difficult things beautifully in this movie, which richly deserves the Oscar consideration it will surely receive. He handles a literary adaptation, he re-creates a lost world that is partly imagined but mostly real, he manages a group of characters from childhood through adulthood, and he gets haunting, underplayed performances from both Mulligan — the real star of this film — and the oft-maligned Keira Knightley, strong and subtle as the greedy, petty and finally penitent Ruth. (Garfield is also good, but his role is less substantial.) But maybe the best and most difficult of them is capturing the philosophical dimension of “Never Let Me Go,” which is difficult to describe with words, let alone pictures.

It’s a truism to say that speculative fiction is always about our world rather than an imaginary world, but it’s certainly true in this case. The specific reality imagined by Ishiguro — a caste system in which some human beings are sacrificed so that others may live — may seem far-fetched. It will strike nearly everyone as morally reprehensible, and even the most hard-hearted science geek would not defend it. But things as bad as that have happened before and will quite likely happen again, and in any case this movie isn’t a lecture about the horrors of human history. It’s more like an allegorical reminder that we all live and die amid confusion and injustice, and that life seems too short no matter how long it lasts, and that the days we have are miraculous and then they are gone.

Posted on September 17th, 2010 at 1:58pm.

I’m reading “The Passage” right now and there’s a moment similar to the hammer-blow moment described here. I was thinking, this one aspect of this 700+ page novel would itself make a riveting stand-alone short.

I hated the novel “Never Let Me Go,” with its presumption, never explained, of utter passivity by the “guinea pigs” (if you will.) I guess I don’t understand what I was supposed to think of these people. Yes, they were presented as living, breathing people who nevertheless surrendered to their fate with nary a whimper. What of the society they served? Who were they? Too many not-bothered-with questions.

Thanks for your thoughts on this, Brian.

Quick question: have you ever seen Michael Bay’s The Island? Or the great 70s cult classic Clonus? I’d be interested in your thoughts if you have.

No, I have not. I can see in my mind what Michael Bay would do with this material 🙂 — and maybe I’m being unfair to Ishiguro. (I’m usually driven crazy by people who say they object to the givens in a work. “Why didn’t they just shoot their way out?” lol) But there it is.

I only bring it up because I thought The Island was unfairly maligned; it was actually pretty fun, as mindless Michael Bay entertainments go.

Oh, cool, so I’m being unfair to Michael Bay *and* Kazuo Ishiguro. Strangest twofer of the day 😉

Expect the unexpected here at Libertas. 🙂

Did the writers or any of the filmmakers involved ever think over how the exact same thing is being attempted today with all the people who want stem cell research with human embryos??? Anyone ever think over that these are real human beings too who should also have a chance to live??

Probably all the film industry liberals who are going to watch this movie are going to cluck and say “how terrible” that these young people are being sacrificed, and then go right ahead and vote for politicians who want to basically harvest human embryos so that other, more privileged humans can live longer.

There are lots of scientists who are finding alternatives to using human embryos – for example stem cells from the plant world – but somehow the liberals don’t want to talk about this and keep pushing to experiment on humans in truly grotesque ways. Will anyone who watches this movie realize this?

Is there some sort of disguised anti-Margaret Thatcher message in this that I need to watch out for, since some of it takes place in England in the 1980s?

HMMM. Seems like it’s about life and choice. It’s funny how people react when things are tilted to a slightly different angle.

Something was legalized in the UK in 1967. Guess what it was. I haven’t seen this, but it seems to me that life chosen at the expense of others isn’t just about living longer.

I read the novel too and did not care for it. It was one of those stylistic literary novels that takes no position on its subject matter. I would imagine the characters in the movie would have to have some kind of personality, and the narrative some kind of arc, so maybe I’ll see it to see how they solved that problem. Remains of the Day was pretty brittle, too, like the book, but maybe this one is different.