By David Ross. Constructing literature courses is relatively easy, because literary history is so coherent and clearly marked – its nodes are so inarguable. You can no more bypass Austen or Dickens in a course on the British novel than you can bypass London on a trip to the UK.

Film, which I will teach for the first time in the Spring, is different. Unlike poetry or even the novel, film is a living form. It continues to unfold and redefine itself, and it forces one constantly to reconsider what seemed fixed. Bergman, for example, may be the greatest director of all time, but his kind of filmmaking – let’s call it filmed theater – seems everyday less relevant, while Godard, who cannot compare as a directorial talent or philosopher, seems to have put his finger on the future. Whom to prefer? Did Mssrs. Lucas and Spielberg reinvent American mythmaking (Mr. Apuzzo’s view, if I’ve understood him correctly these twenty years), or did they infantilize our popular entertainment (my view)?

And what of those beloved heirlooms of Hollywood’s golden age that are neither entirely art nor merely entertainment, and that, in any case, nobody younger than fifty has particularly bothered to see? Are they historical artifacts, national treasures, charming baubles, or inadvertent masterpieces? In teaching them, do we chronicle the American Spirit or do we dumb down the curriculum? In general, is film high art or popular art – a belated expression of the old Renaissance aspiration, or a symptom of capitalist energy and mass consumption?

Designing my course – “Film and Society” – was a two-tablet headache due to the unanswerable questions above. I was not sure what a film course should be, because I have only a confused idea what film is and what it’s for. In the end, I treated film as high art on the model of literature, not because this makes the most or best sense of film as a medium, but because students have so little exposure to the old Renaissance aspiration, and because no opportunity to complicate their sense of the sufficiency of Avatar and Twilight can be passed up. At the same time, one must make certain concessions (Miyazaki for example) in order to avoid civil unrest and student evaluations drenched in one’s own blood (see here).

Not long ago, I described Into Great Silence (2005), a documentary about life in a Carthusian monastery in the mountains of France, as “one of the more difficult and beautiful films ever made, and perhaps film’s most sincere and respectful attempt to portray the life of religious devotion.” It occurs to me that Ordet (1955), even more so, knows how to bend its Medieval knees (to borrow a phrase from Yeats).

I would have liked to teach the Tykwer-directed, Kieslowski-penned Heaven (2002) in conjunction with A Serious Man (2009). The films are fascinatingly obverse. The former concerns a seemingly compromised woman who experiences a mysterious and miraculous beatitude; the latter, a seemingly righteous man who suffers endless punishment.

My syllabus is still germinal. I would, of course, appreciate any advice. One thing to keep in mind is that the course is already busting a seam. Adding necessarily entails subtracting.

The Palace of Art

- The Mystery of Picasso (1956, Henri-Georges Clouzot)

- 8 1/2 (1963, Federico Fellini)

- Russian Ark (2002, Aleksandr Sokurov)

- Hero (2003, Zhang Yimou)

Masculin/Feminin

- A Woman is a Woman (1961, Jean Luc Godard)

- Woman of the Dunes (1964, Hiroshi Teshigahara)

- My Night at Maud’s (1969, Eric Rohmer)

- Annie Hall (1977, Woody Allen)

God in the Dock

- Ordet (1955, Carl Theodor Dreyer)

- Aguirre: The Wrath of God (1972, Werner Herzog)

- Fanny and Alexander (1983, Ingmar Bergman)

- A Serious Man (2009, Coen Brothers)

The Smell of Napalm in the Morning

- The Grand Illusion (1937, Jean Renoir)

- The Battle of Algiers (1965, Gillo Pontecorvo)

- Shame (1968, Ingmar Bergman)

- Apocalypse Now (1979, Francis Ford Coppola)

Earth Abides

- Derzu Uzala (1975, Akira Kurosawa)

- Stalker (1979, Andrei Tarkovsky)

- My Neighbor Totoro (1988, Hayao Miyazaki)

- Maboroshi No Hikari (1995, Hirokazu Koreeda)

Utopias and Dystopias

- Smiles of a Summer Evening (1955, Ingmar Bergman)

- Raise the Red Lantern (1991, Zhang Yimou)

- Koyaanisqatsi (1982, Godfrey Reggio)

- The Lives of Others (2007, Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck)

Brave New World

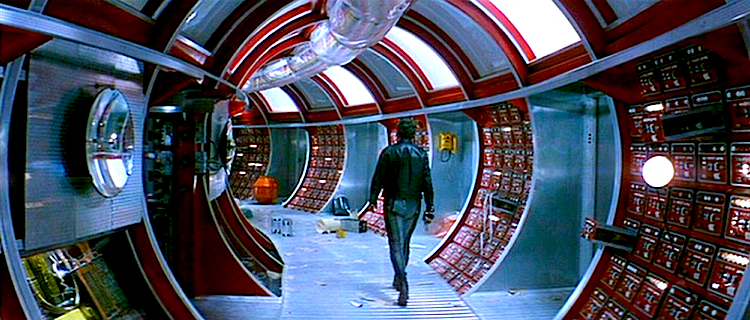

- 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968, Stanley Kubrick)

- Solaris (1972, Andrei Tarkovsky)

- Cache (2005, Michael Haneke)

- Encounters at the End of the World (Werner Herzog, 2007)

Other films I seriously – yearningly in some cases – considered, but in the end could find no place for:

- La Ronde (1950, Max Ophuls)

- Diary of a Country Priest (1950, Robert Bresson)

- Secrets of Women (1952, Ingmar Bergman)

- The Earrings of Madam de … (1953, Max Ophuls)

- Cleo from 5 to 7 (1961, Agnes Varda)

- Woman of the Dunes (Hiroshi Teshigahara, 1964)

- A Clockwork Orange (1971, Stanley Kubrick)

- The Sorrow and the Pity (1972, Marcel Ophuls)

- Yellow Earth (Chen Kaige, 1984)

- Wings of Desire (1988, Wim Wenders)

- Lessons in Darkness (1992, Werner Herzog)

- After Life (1999, Hirokazu Koreeda)

- Heaven (2002, Tom Tykwer)

- Grizzly Man (2005, Werner Herzog)

- 24 City (2008, Zhang Ke Jia)

Posted on September 14th, 2010 at 11:22am.

Grand Torino Clint Eastwood

Unforgiven Clint Eastwood

Limelight Charles Chaplin

Greasers Palace circa 1971

Fearless starring Jet Li

Seven Samurai Kurasawa

Roshomon Kurasawa

Here’s some of my answers to the questions above:

1. Lucas and Spielberg did reinvent American mythmaking, in my opinion. Whether or not some cinema was infantalized or not afterward is not their fault. Both men honored those who came before them, and have always carried forth the language of modern cinema as established by Kubrick, Hitchcock, Ford, Kurosawa, and others.

2. “And what of those beloved heirlooms of Hollywood’s golden age that are neither entirely art nor merely entertainment, and that, in any case, nobody younger than fifty has particularly bothered to see? Are they historical artifacts, national treasures, charming baubles, or inadvertent masterpieces?”

– They are ALL of those, and they should be taught in comparison to the modern era. For instance, I feel so much depended on casting at the time, and the relationship between stars and the public was much different today. Considering the context, the teachable moment there is actors’ contribution to the collaboration.

3. Treating film as high art on the model of literature is the right thing to do, but don’t dismiss the relationship both have had on each other. This would be a great part of the class. For instance, books are almost exclusively written like screenplays today. No publisher will read your book if you do a lot of “telling” rather than “showing”. Books are MUCH more cinematic these days.

Some films I would show for no particular reasons would be:

1. The Fountainhead (relationship between film and literature, especially since author and screenwriter were the same here)

2. Bram Stoker’s Dracula (best opening in film history)

3. Gran Torino (film as allegory)

4. Ride the High Country (evolution of a director)

5. On The Waterfront (political context)

6. Duel in the Sun (pulp cinema)

7. Star Wars (digital cinema, and the inclusions of more art forms in the collaborative effort)

Congratulations on your film course, David! It’s good to know that the cinematic doctrines of Libertas will be spread far and wide to impressionable young minds …

In terms of adding some films, I think it would be wonderful to include some films that portray American individualism – how about a John Wayne movie like “The Searchers” which many see as a Western version of the Medieval Grail romance – or movies that portray democratic values – like Elia Kazan’s “On the Waterfront” or Capra’s “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington”? Or, since this is “Film and Society,” one could delve into post-World War II dislocation by discussing stunning film noirs like Rita Hayworth’s “Gilda,” Hitchcock’s “Notorious,” Reed’s “The Third Man,” or Welles’ “Touch of Evil.”

Or how about a historical epic like “Lawrence of Arabia,” “Gone With the Wind,” or “Ben Hur”? These kids are often so ill-educated about history that these films may really excite and inspire them – as they excite and inspire me every time I see them. These films certainly convey the importance of individual achievement in a society that increasingly favors collectivism …

There’s a lot more I could suggest, but I think since you have the opportunity here to reach some young minds, they should see a few more classics from the American cinema. I know these may seem like films that everyone’s seen, but for young students who today are almost guaranteed to have never seen a classic American film, these may be revelatory viewing experiences.

I think saying Spielberg “infantalized” American cinema is kind of snobbish, no offense. I am not a fan of his latest work, but go back and watch Jaws and the movie holds up, even in this modern age of digital effects. It is just a well paced thriller. Setting aside Jaws, Raider’s of the Lost Ark might be the most perfect action/adventure film made in the 20th century.

You certainly seem to lean towards a lot of the foreign films, which is fine; you never claimed to be teaching a course in American Cinema. I like the inclusion of Miyazki, he is a gem, too often overlooked by people who refuse to ackowledge cartoons as a serious art form.

Govindini,

You’re certainly right that kids have not seen the classics — in fact, there’s no particular likelihood that they have seen even “Star Wars” or “Indiana Jones.” I once did a hand-count on “Stars Wars” and was astonished to discover that fewer than half of the students had seen it. I once did a hand-count on “Casablanca” — dead blank. Nobody. Film is no longer a culturally central experience for young people, as it was even for our relative belated generation (I was born in 1970). Kids watch films, but they find nothing magical or sexy about the medium itself and they certainly have no interest in the history of the medium. I suppose the cutting-edge alternatives to one’s school work are…what? Japanese comic books? On-line role-playing games? I have no idea, honestly.

I considered the classic Westerns, but these were hard to fit into my aggressively philosophical format. I though about a unit on “politics,” into which “Mr. Smith” would have fit nicely, but I had trouble fleshing it out. I also had a unit titled “The Burden of History.” I had in mind films like “The Sorrow and the Pity” and “Russian Ark,” but the idea likewise fizzled. “Lawrence of Arabia” might have worked in this context. It’s funny you should mention the Grail Quest. I began with a unit on the quest. “Aguirre” and “Apocalypse Now” were to have been the linchpins. “The Searchers” would have fit in nicely. In the end, the theme seemed to wander from the course description.

I can only hope that I have the chance to teach the course again. I usually take a different approach on the second go-around, both correcting for whatever didn’t work the first time and attempting to keep the course fresh for my own sake.

I agree with the assessment that the “canon” of film is much harder to establish than the canon of literature or even philosophy. Part of the difficulty is that so many of the so-called “great” filmmakers make beautiful movies, not great ones. It seems that many critics are easily impressed with the style of movies and less with its actual content. A modern example of such tendency is Terence Mallick. The Thin Red Line is a film which looks and sounds spectacular, with a musical score one does not easily forget. Unfortunately it is also essentially nihilistic and completely unrealistic. Its depiction of war is false, its “account” of World War II is wholly inaccurate, and its portrayal of soldiers on the battlefield is an offense to how the US military actually operates. In short the film is a beautiful lie. As of today it stands with a comical 95% “fresh” rating from the “top critics” over at Rotten Tomatoes. Simply shameful.

With Malick, we can add a whole list of other equally gifted filmmakers whose artistic ability are unquestioned but whose films are nevertheless devoid of any compelling message: Kubrick, Coppola, Scorcese, Eastwood etc. Their films usually tend toward a kind of adolescent nihilism where the characters inhabit whatever distorted idea of reality the directors believe in. Does Sorcese actually believe the New York City he shows us in Taxi Driver is anything remotely real? When Travis Bickle, a homicidal sociopath, is one of the most appealing characters in the film; shouldn’t it give us a shudder at what humanity is composed of? Ultimately such directors have nothing redeeming to say about human nature and their misanthropy is a sorry excuse for their “intellectualism.” Pick up a copy of Hobbes’ Leviathan, it is there you will see the political consequence of such a view of human nature.

Moving from the nihilism of such directors, we can now turn to the “moralism” of Spielberg and Lucas. What have they shown us? Nazis are bad? The extermination of six million Jews was a crime against humanity? Giant men-eating sharks should be stopped? The good side of the “force” is preferable to the dark? Who exactly has ever watched one of their films and walked away with anything new or interesting? They make trite, pedantic art, where the good guys win and the bad guys get blown up. Their cinema is one for children (at best) but it has somehow invaded the realm of “high art” and is now discussed as seriously as Shakespeare’s Tragedies. Courses across American universities discuss the relative merits of Star Wars and how Ewoks are really just like the Native Americans! Ah post-modernism! The art of appearing to speak intelligently of things which are really not. The Ancients already had a name for this, they called it sophism.

Ultimately there is very little difference between Kubrick’s nihilism and Spielberg’s moralism. They are opposite sides of the same coin. Unable to express a morally satisfying vision of humanity, they fall back on cliches, stereotypes, or despair, whichever they may be in the mood for. In fact when Spielberg decided to make a “serious” film (Munich), his protagonist ended up a disillusioned ex-Mossad agent, unsure of who he was fighting or why. Is that really possible Mr. Spielberg that after showing us so vividly the horrors of the Holocaust you are unable to formulate a reason as to why the defense of the state of Israel is so vital to the civilized world?

A serious canon of film can only be composed after removing those charlatans from the history of cinema.

I have to agree with most of this forcefully worded statement. I am second-to-none in my Spielberg and Lucas detraction, as Mr. Apuzzo can attest, and I’ve never had much use for Eastwood as a director (though I’ve loved him as a movie star, and “Gran Torino” sat well enough with me). Scorsese began with a certain promise, but “Taxi Driver” deserves much of the derision you direct at it, and in any case, Scorsese has not made a decent film in thirty years. His latest, “Shutter Island,” should be called “Shitter Island.” My best Scorsese film remains “Mean Streets.” I would largely exempt Kubrick from this scorched earth campaign. “Dr. Strangelove” and “Full Metal Jacket” certainly have a vein of cheap nihilism, but not so “2001.” Compare these American directors to the two great world directors of the same period — Tarkovsky and Kieslowski. It is to compare children and men.

David,

Apologies if my post came across all “doom and gloom”, I just find it exasperating how so many film students accept whatever the critical establishment decrees. On a more positive note, I actually find Kubrick’s “The Killing” to be his best film. Concise editing, an ingenious plot, terrific acting, at 83 minutes the film is never boring. Working in the confines of film noir, Kubrick’s pessimism and dark humor actually work.

I do have some recommendation for your film class:

Masculin/Feminin: “Jules et Jim” (1962)

The Smell of Napalm: “Das Boot” (1981), “Black Hawk Down” [essentially a modern day battle of Thermopylae] (2001), “Sergent York” (1941)

Brave New World: “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind” (2004)

God in the Dock: “The Mission” (1986), “Revanche” (2008)

Other films: “Bottle Rocket” (1996), “Les 400 Coups” (1959), “Young Mr. Lincoln” (1939), “The Searchers” (1954), The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance” (1961), “Rope” (1948), “La Regle du Jeu” (1939), “Trainspotting” (1996) etc.

Sad how few of these I’ve seen.

Based on my years of experience as a film student, documentarian, and film professor, I must say that your class should be called, “My pretentious list of high art films that you’re probably not going to like.” I do not see how you are giving your students a sense of Film and Society with this, “aggressively philosophical format.” Honestly, what society do you live in and who is this class for? The one erudite student who wants validation that s/he is better than everyone else? Or maybe the one erudite professor who wants to feel he did his best to uplift the masses?

My advise:

1) Play only a few films in their entirety. Play a lot of clips that expose them to a wide variety of forms and ideas. That way most everyone can find something that clicks with him/herself and not feel like they are suffering through the vast majority of the material that does not click for them.

2) Show Visions of Light, a doc about cinematography, and The Cutting Edge, a doc about editing. Give them a better sense of what these things are, how they actually work, and why film was so revolutionary.

3) Given them a sense of film history; how it has changed our society and been changed by it. Use the different eras of film history to teach them a little something about the wider societal history and show them that the past is not just a collection of dry dates and facts.

4) Focus on the society that they actually live in and do not avoid popular art, just because a wide variety of people are stupid enough to like it.

5) Save the philosophical categories for a class on Film and Philosophy or Philosophy in Film.

OK, hopefully that didn’t sound too rude. I can assure you that I am being a lot less arrogant to you than you are to your students.

Best,

JKL