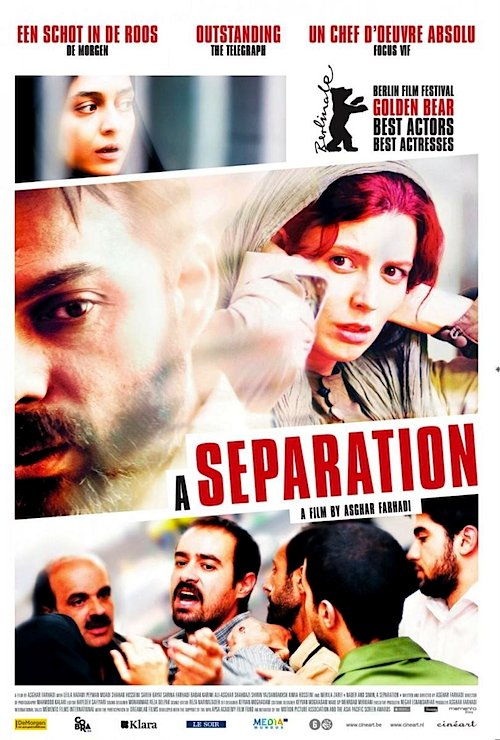

By Joe Bendel. As a well educated, comparatively liberal Iranian woman, Simin wants to live abroad -not so much for herself, but for her daughter Termeh. Unfortunately her travel visa will soon expire and her husband Nader refuses to leave. It causes what westerners would call irreconcilable differences for the couple. It also sets in motion a tragic chain of events that will jeopardize their way of life in Asghar Farhadi’s Golden Bear winning A Separation (trailer here), which screens during the 49th New York Film Festival.

By Joe Bendel. As a well educated, comparatively liberal Iranian woman, Simin wants to live abroad -not so much for herself, but for her daughter Termeh. Unfortunately her travel visa will soon expire and her husband Nader refuses to leave. It causes what westerners would call irreconcilable differences for the couple. It also sets in motion a tragic chain of events that will jeopardize their way of life in Asghar Farhadi’s Golden Bear winning A Separation (trailer here), which screens during the 49th New York Film Festival.

Nader is not exactly a fundamentalist, but he is stubborn. He also must care for his Alzheimer’s stricken father, though Simin considers this a questionable excuse. Since divorce is not an easy no-fault proposition in Iran, she moves back in with her parents as their case drags on. Requiring help with his father, Nader hires Razieh as an in-house aide. She is poor, uneducated, extremely religious, and married to the abusive Houjat.

She only accepts the position in place of Houjat when the deadbeat is thrown in jail for his debts. Yet, as soon as she appears to settle into the routine of the household, a moment of chaos turns their world upside down. Suddenly, Nader is on trial for causing the death of Razieh’s unborn child while the thuggish Houjat harasses his family.

Granted, A Separation’s portrayal of Iranian jurisprudence does not inspire a lot of confidence, but it is almost the least of Nader’s problems. Instead, he becomes his own worst enemy, responding to Razieh and Houjat in the worst possible way at every juncture. Yet explaining his decisions to his acutely sensitive daughter is often his greatest challenge.

Much like Farhadi’s Tribeca award winning About Elly, Separation vividly depicts how one tragic mistake compounds over and over again. It is an intense film, almost to the brink of exhaustion. Like many of the persecuted Jafar Panahi’s films, it shines a searing spotlight on the divisions of Iranian society, largely cleaving along professional and secular-as-they-dare versus poor and fundamentalist lines. Ostensibly, Nader and Simin should have the upper hand, but this is Iran.

Separation is also smart and scrupulously realistic on the micro level, as well. The relationship dynamic between Simin and Nader is particularly insightful, rendered with great sensitivity by leads Leila Hatami and Peyman Moaadi. We clearly understand this is a couple with a lot of history together who do not hate each other. They are unable to make it work, but they cannot stop trying. Likewise, teenage Sarina Farhadi (the director’s daughter) gives a finely-calibrated performance as the insecure Termeh.

Separation is also smart and scrupulously realistic on the micro level, as well. The relationship dynamic between Simin and Nader is particularly insightful, rendered with great sensitivity by leads Leila Hatami and Peyman Moaadi. We clearly understand this is a couple with a lot of history together who do not hate each other. They are unable to make it work, but they cannot stop trying. Likewise, teenage Sarina Farhadi (the director’s daughter) gives a finely-calibrated performance as the insecure Termeh.

Separation and Elly before it are like Iranian Cassavetes films, uncomfortably intimate and direct, but undeniably visceral in their impact. Their place within the contemporary Iranian cinema establishment is a little trickier to pin down. Separation had to be produced outside the official film system without government support after Farhadi cautiously spoke out on behalf of the imprisoned Panahi and Mohsen Makhmalbaf. Reportedly, though, he has since walked back those comments and Separation was subsequently chosen as Iran’s official submission for best foreign language Academy Award consideration. It is hard to judge an Iranian artist for whatever survival strategies they might employ. Regardless, Separation is an unusually powerful film. Highly recommended, it is easily one of the best of the festival. It screens this Saturday and Sunday (10/1 and 10/2) at Alice Tully Hall as a Main Slate selection of the 2011 New York Film Festival.

Posted on September 28th, 2011 at 11:54am.