[Editor’s Note: the post below appears today on the front page of The Huffington Post.]

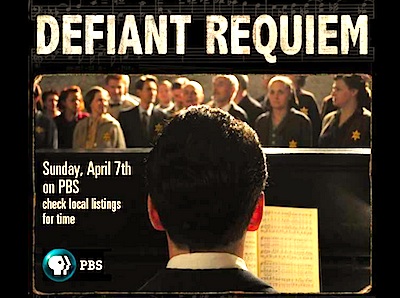

By Jason Apuzzo & Govindini Murty. If a hallmark of great art is its ability to transcend the limited circumstances of its creation, then there is no more heartbreaking realization of this than the 1944 performance of Giuseppe Verdi’s Catholic Requiem by Jewish prisoners at the Nazi concentration camp Terezín. The story of Terezín and of the Requiem is told eloquently in director Doug Shultz’s powerful new documentary Defiant Requiem, which premieres this Sunday, April 7, on PBS at 10 p.m. ET/PT (check listings for additional screenings on local PBS stations).

It was at Terezín in 1944 that imprisoned Czech conductor Rafael Schächter led a chorus of his fellow Jewish prisoners — most of them doomed to the gas chambers at Auschwitz — in brazenly performing Verdi’s Requiem before the very Nazis who had condemned them to death. One of the most complex and demanding of chorale works, Verdi’s 1874 Requiem was originally intended as a musical rendition of the Catholic funeral mass. Rafael Schächter took Verdi’s music and transformed it into a universal statement, one proclaiming the prisoners’ unbroken spirit and warning of God’s coming wrath against their Nazi captors.

Defiant Requiem tells two parallel stories: the first takes place during World War II, when Jews throughout Europe were rounded up by the Nazis and sent to Terezín as part of an elaborate deception to convince the world that Germany treated its prisoners humanely. Among those arrested and dragged to Terezín in 1941 was the young Rafael Schächter, a courageous and steadfast Czech opera-choral conductor.

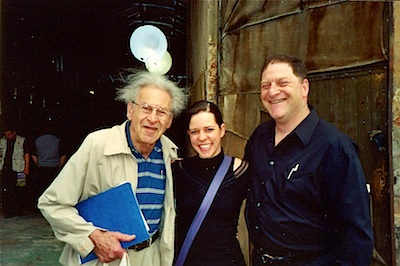

Distinguished American conductor Murry Sidlin, who discovered the history of Schächter and the Terezín performers in the ’90s, and who went on to found and conduct the Defiant Requiem concerts, notes in the film that “Schächter would have emerged as a great conductor” had his life not been cut short by the Nazis.

Within the confines of Terezín, Schächter lifted the spirits of his fellow inmates by creating a musical program for them to perform — a program that inspired an astonishing outburst of cultural activity, which would eventually include almost a thousand different performances of chamber music and operas, oratorios and jazz music, theatrical plays, and some 2,300 different lectures and literary readings. Included in this were 16 performances of Verdi’s emotional and musically challenging Requiem. As Terezín survivor Zdenka Fantlova explains in the film: “Doing a performance was not entertainment. It was a fight for life.” She later adds, “If people are robbed of freedom, they want to be creative.”

This flurry of activity within the walls of the prison camp — achieved under the most trying possible circumstances of starvation, disease, and abject cruelty — would culminate in a performance on June 23, 1944, of the Requiem in front of the camp’s Nazi brass, visiting high-ranking SS officers from Berlin, and gullible Red Cross inspectors brought in to verify that the prisoners were being well treated.

It was at this point that Verdi’s Requiem, with its dark, apocalyptic Dies Irae (“Day of Wrath”) choral passage — evoking the Last Judgement — and equally harrowing Libera me (“Deliver me”) passage took on connotations that Verdi could hardly have imagined. Serving as both a spiritual catharsis for the prisoners, and as a prophecy of the Nazis’ ultimate fate, the Requiem was immediately transformed by Schächter and his fellow prisoners into an anthem of divine supplication and retribution. Indeed, shortly after this final performance, both Schächter and most of his choir would be sent to Auschwitz.

Defiant Requiem‘s second, parallel story takes place in 2006, as Murry Sidlin brings a full orchestra and the Catholic University of America’s chorale ensemble — along with surviving members of Schächter’s chorus — back to Terezin to perform the Requiem once more, this time in tribute. (Sidlin continues to conduct such tribute performances of the Requiem, with concerts scheduled for The Lincoln Center on April 29 and Prague’s St. Vitus Cathedral on June 6.)

The journey to Terezín is clearly a spiritual quest for Sidlin (who has since founded The Defiant Requiem Foundation), who views the modern performance of the Requiem at Terezín as the completion of something begun seventy years before. As Sidlin says at one point in the film: “I brought the Verdi here because I want to assure these people [Schächter and the deceased prisoners] that we’ve heard them.” Sidlin’s staging of the Requiem in the now unassuming confines of Terezín is powerful and gripping — and serves, one senses, as the perfect tribute to Schächter and his fellow performers.

Highlighting the role that individuals can play in keeping important cultural history alive, it was Sidlin’s discovery of the book Music at Terezín in the late ’90s, and his subsequent championing of the concert series, that has brought the otherwise forgotten history of Rafael Schächter and the Terezín Requiem performances back to life. It is a culmination both of Sidlin’s passion for music and of his own personal history; Sidlin’s grandmother and many of her closest relatives were murdered outside Riga, Latvia by Nazi SS assassination squads during World War II.

This June, Sidlin will be awarded the Simon Wiesenthal Center’s Medal of Valor for his efforts to commemorate Rafael Schächter and the Terezín prisoners.

When we spoke with Sidlin recently, he recounted to us the special nature of Rafael Schächter’s connection to Verdi’s music. Sidlin noted that the young conductor had taken the score of the Requiem with him as one of his few prized possession to Terezín.

“I’m convinced that if he could have cut himself open and taped that score to his heart, and then bound himself up, he would have done so. It was that important to him,” Sidlin explains. “It [the Requiem] is the kind of work that you read late at night and it gives you assurance — of strength, of courage, of hope and dignity and renewal and memories.”

As survivors recount, the performance of Verdi’s music fed the souls of the Terezín prisoners, giving them something to look forward to in the midst of 12-hour days of slave labor, disease, cold, starvation, and executions that would eventually kill 33,400 of them — along with deportations to Auschwitz that would kill another 88,000 prisoners from the camp.

Survivor Edgar Krasa says of the Requiem, “It was a prayer that overcame hunger … you were there [singing] in that cellar and you were a different person.” Another survivor who sang in the chorus, Marianka May, agrees: “My stomach stopped growling when I was singing. I think when you are more a soul than a person, I don’t think the soul has to be nourished by anything but heavenly music.”

Art was not a theoretical matter to them, nor was it mere entertainment. As Sidlin notes, “Vera Schiff — who is in the film — said to me once: ‘The Nazis knew that if you kill the soul, the body will follow.'” Sidlin exhorts, “So keep that soul ignited.”

Sidlin further explains that after years of not being allowed to perform, teach, or study the arts in Nazi-occupied Europe, for the Jewish prisoners of Terezín,

“Doing the Verdi Requiem — this was a pinnacle for them … Schächter chose this work not only because it was a crowning achievement artistically, but also because it was raising the fist, it was defiance and resistance, it was saying all those things to the Nazis about the Day of Wrath [that they couldn’t say otherwise].”

Participating in the 2006 Requiem concert at Terezín was an emotional experience for the contemporary performers. Actor/singer/dancer Lisa Ferris was an undergraduate in music at the Catholic University of America when she participated in the first Defiant Requiem concert at Terezín (two more concerts have been performed there subsequently). As Ferris recalls, “It very quickly became about something more than just getting all the notes right. It was about creating a memorial to this group of people.”

Ferris befriended Terezín survivor Edgar Krasa (featured in the documentary), Rafael Schächter’s roommate and assistant on the original Requiem performances. Krasa’s sons, Rafael (named after Schächter) and Daniel would sing in the Defiant Requiem chorus with Ferris. Ferris says of Edgar Krasa:

“He is so full of life in a way I’d never seen before – his wife [Hana Krasa, also a Terezín survivor], as well. He has such joy. He is a human manifestation of how you can’t destroy the human spirit. And the musical performance was a microcosm of that.”

When asked about the emotional impact of performing at Terezín, Ferris admitted, “It wasn’t easy. Those kinds of experiences are haunting.” Ferris grew emotional as she described the moment when Sidlin took the performers down to the cellar where the original Terezín chorus had rehearsed:

“We were down there for ten or fifteen minutes, and the air down there was suffocating. It was dark and moldy and hard to breathe. To hear how this group of people, with one score and a broken piano, rehearsed in this place where you couldn’t even breathe – and [yet] they created this epic piece of music.”

Sidlin confirms this experience:

“I think we were doing OK until we went down into the cellar, and that was a transformative moment. We realized that after twelve hour days, they [Schächter’s chorus] had to drag themselves, walking over dead bodies, by choice coming down here, where it was freezing – no light, no air – standing next to people who are sick, and standing next to everyone who is hungry, and to do this night after night.”

Schächter’s original Terezín chorus had to learn the entire Requiem score by heart, due to only having one score to share among the 150 of them. And as Sidlin explains, Schächter was demanding.

“Edgar Krasa says he was merciless, and it wasn’t because he was a tough conductor. It was because he would not let their minds wander. He would not let their minds go inside themselves and think about the things he wanted them to overcome, which included things like: Where are my children? Where is my wife? Where is my husband? These are incredibly difficult things to imagine.”

Lisa Ferris concludes of the experience: “If you are a performer, you are lucky enough to have a handful of experiences that change you, that you carry with you for years to come. … Every person with a heart feels connected to this group of people in 1944.”

Defiant Requiem also presents recreations of cultural life at the Terezín camp – along with animations adapted from surviving Terezín drawings – and features poignant reminiscences from the camp’s survivors. The survivors themselves are uniformly remarkable for their eloquence and equanimity.

As a horrifying counterpoint to the Terezín survivors’ memories, and reinforcing the depth of the Nazis’ sadism, Defiant Requiem also presents surviving Nazi propaganda footage of Terezín as it was perversely stage-managed during a Red Cross inspection visit to appear like an attractive Jewish commune, a Potemkin village of Third Reich magnanimity. Children play in the grass and eat butter off slabs of black bread, adults compete vigorously in soccer, a pleasant outdoor café bustles with life and activity. As Defiant Requiem‘s narrator Bebe Neuwirth informs us, many of the people shown in the footage would within weeks be shipped to Auschwitz in cattle cars for extermination — including some 15,000 children, some as young as three years old.

In telling the largely forgotten story of the Terezín camp, Defiant Requiem adds meaningfully to the body of knowledge about the Holocaust — but it also adds a new twist to debates over the political and rhetorical uses to which music is put. Given the Nazis’ adoption of Richard Wagner’s operas as a soundtrack for their program of national mythic renewal (with which Schächter as an opera conductor would have been familiar), it may be said that Schächter’s adoption of Verdi’s Requiem hoisted the Germans on their musical petards. Schächter would later be joined in this endeavor by such artistic luminaries as Thomas Mann, whose famous 1947 novel Doctor Faustus associated music of the German Romantic tradition with the diabolism of the Nazi era.

When we asked Sidlin what Verdi’s Requiem means to him as a work of music, Sidlin responded:

“It used to mean singing in tune, playing precisely. It used to mean following Verdi’s dynamics and his metronome markings, all those things that don’t matter … Now it means this: an opportunity to give Rafael Schächter something of the career he never had – as a real hero, as an artistic hero. That’s number one.”

“And number two is that Verdi’s Requiem is way beyond beautiful, powerful, dramatic music. The internal meaning of the Verdi is now: ‘What is our spiritual obligation as humans?’ It reminds us of people in a concentration camp with no food, no medical attention, freezing, sick, terrified, who stepped forward and taught us what the Verdi Requiem means.”

When asked how this experience has changed him, Sidlin told us:

“It’s not only changed me personally, it’s changed my whole focus. My whole professional life now is dedicated and devoted to illuminating the legacy of Terezín and what a major role the arts and humanities play in that mission. It’s an exercise in seeking a connection with history – and therefore being able to well serve the future.”

For the viewer, what ultimately remains after watching Defiant Requiem is the intense reality of what singing Verdi’s music meant to the prisoners of Terezín who had been condemned to death. As Terezín survivor and original chorus member Marianka May explains it: “Verdi’s Requiem put all of us into another world. This was not a world with the Nazis. This was our world. […] We just tried to reach something that’s bigger than we are … and let’s hope that we are singing to God, and God can’t help but hear us.”

Highly recommended, especially for those interested in the cultural history of the Holocaust or in classical music, Defiant Requiem premieres this Sunday, April 7th on PBS at 10:00 p.m. ET/PT (see local listings).

[Editor’s Note: Libertas readers can also read Joe Bendel’s review of Defiant Requiem here.]

Posted on April 6th, 2013 at 4:43pm.