[Editor’s note: the post below appeared yesterday at The Huffington Post.]

By Jason Apuzzo. Sunny southern California rarely gets its due at the movies. Ever since the 1940s, when film noir classics like Double Indemnity and The Big Sleep depicted Los Angeles as a dark urban labyrinth, you might get the feeling that southern California has remained in a permanent Blade Runner nightfall of neon signs, wet streets and detectives pulling fedoras down over their eyes. A world of call girls and corrupt police, of murder and car crashes; a bleak landscape of paparazzi and Black Dahlias, of washed-up actresses and sleazy district attorneys who wear too much aftershave.

It’s a shadowy, sexy and malevolent vision — except that it’s not really the day-to-day SoCal that longtime residents know and (mostly) love. Actually, the place is a lot brighter and more cheerful than that. And a lot goofier.

For one thing, southern California is actually huge, wide-open and flat — with endless horizons, whether of the Palm Springs or Redondo Beach variety — instead of the cramped, angular spaces you typically find in crime thrillers. And it’s got color — lots of color, from the saturated blues of the ocean and sky, to the lurid red-and-gold Fatburger signs on Pacific Coast Highway. Whoever dreamt up southern California was clearly dreaming it in 65mm Ultra Panavision Technicolor.

And contrary to popular belief, most people in southern California don’t pack guns or talk like they just stepped out of a Raymond Chandler novel, diverting as that would be. Most SoCal residents are sedate, middle-class people with just a hint of craziness to them — that quiet spark that drove them long ago to pack up and leave the East Coast/Midwest/Deep South to pursue their pot of gold right here in the Golden State.

And this brings us to It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World.

And this brings us to It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World.

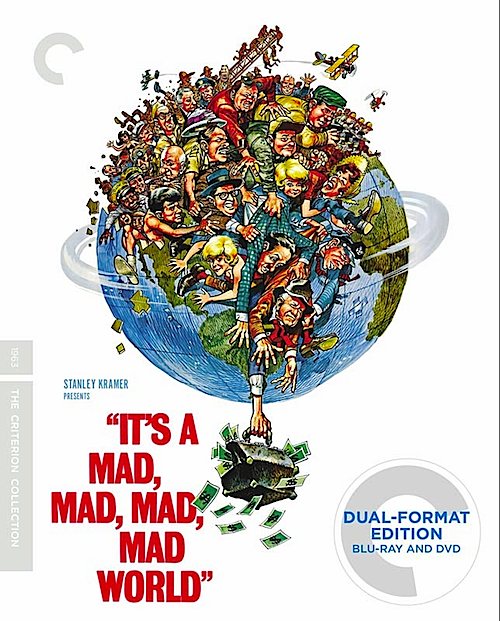

The wonderful folks at Criterion, who are forever saving our cinematic heritage from the ravages of time and neglect, have recently outdone themselves in producing a five-disc set (two Blu-rays + three DVDs) of It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, all built around a pristine 4K transfer of the film and a newly restored 197-minute ‘roadshow’ version of the movie not seen in 50 years. (See a video on the restoration at the bottom of this post.)

And this new, authoritative version of director Stanley Kramer’s beloved epic comedy makes one thing abundantly clear: that It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World is the ultimate southern California movie.

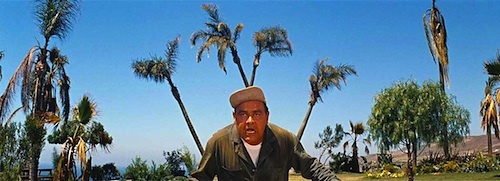

For those unfamiliar with the film, It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World depicts a pack of otherwise unremarkable southern Californians unleashed in a frenzy of greed when they learn that a stash of $350,000 in stolen money is waiting for them, ready to be dug-up in a park at Santa Rosita Beach (in real life, Portuguese Bend in Rancho Palos Verdes). Unable to come up with an equitable way of sharing the loot, the group breaks up into separate teams, frantically racing toward their hidden treasure by land and air — comedian Jonathan Winters even rides a girl’s bicycle for a while — all while the Santa Rosita Police, led by Spencer Tracy, tracks their progress.

So it’s off to the races, as airplanes smash through billboards (and even a restaurant at one point), cars roar off cliffs and bridges, an entire gas station is demolished, cast members are flung through the air by an out-of-control fire ladder, and every major speed law in southern California is broken. And although the wild conclusion of the film — a Hitchcockian visual effects extravaganza filmed in downtown Long Beach — leaves none of the avaricious group satisfied with their financial arrangement, it does leave everyone with smiles on their faces. (You’ll have to see the movie to find out what that means.)

And that’s really it. The premise of Mad, Mad World — greed — couldn’t be simpler, but it’s enough to power a non-stop, three-plus-hour chase from Yucca Valley to Santa Clarita to Malibu, all filled with dangerous stunts and comic gags performed by the greatest comedians of their time: Milton Berle, the recently passed Sid Caesar, Mickey Rooney, Jonathan Winters, Buddy Hackett, Phil Silvers, Terry-Thomas, Ethel Merman, Peter Falk and Jim Backus, just to name a few. Mad, Mad World also features spot cameos from the likes of Jimmy Durante, Jack Benny, Buster Keaton, Don Knotts, Jerry Lewis, Carl Reiner, The Three Stooges and more comedy talent than you can shake a stick at.

Mad, Mad World was a huge box-office hit in its day; adjusted for inflation, the movie would’ve made around $450 million domestically in today’s dollars (more than last year’s box office champ, The Hunger Games: Catching Fire). In the wake of the Oscars, it’s also worth noting that the film won the first ever Oscar for Best Sound Editing (Walter Elliott, the film’s sound editor, was a pioneer who’d previously worked on King Kong, Citizen Kane and The Thing), and the film was otherwise nominated for its color cinematography, editing, sound recording, music score, and original song. So the film looks and sounds great, and is one of those epic experiences — like The Searchers or Lawrence of Arabia — that justifies the added expense of Blu-ray.

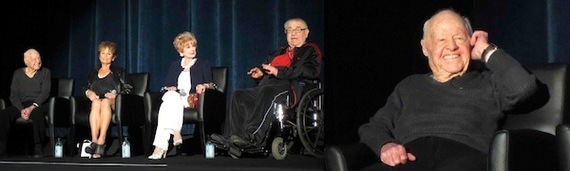

Criterion’s release concludes the busy 50th anniversary of the film, a year that brought both highs and lows. Among the highs were last year’s 50th anniversary screening of the film at the Cinerama Dome — a structure originally built to house Mad, Mad World‘s premiere — hosted by the TCM Classic Film Festival (which returns to Hollywood April 10th-13th), and featuring delightful appearances from cast members Mickey Rooney, Marvin Kaplan, Barrie Chase and director Stanley Kramer’s widow, Karen (see images below; and here’s video of the event).

Govindini Murty (co-editor of Libertas Film Magazine and a fellow Huffington Post blogger) and I had the pleasure of attending this screening — and seeing the film in its full, Cinerama/six-channel glory with cast members present was nothing short of thrilling.

One of the many amusing moments during the Q & A at the TCM screening was when Karen Kramer pulled out a jeweled handbag made from one of the coconuts from the “Big W”‘s famous coconut trees; Mickey Rooney leaned over with an impish grin on his face and said: “That’s a mad, mad, mad handbag.” One could see in Rooney — and in all the cast members present — the irrepressible humor and zest for life that animates their brilliant work in the film. It was a testament to how to live — and how to still have that spirit fifty years later.

Among the lows in the past year, however, were the passing of both Jonathan Winters (just a few weeks prior to the TCM screening) and, more recently, of Sid Caesar. If nothing else, Mad, Mad World represents the most memorable work either of them did in the movies.

The Criterion release contains a host of excellent bonus features, but the set’s main attraction is clearly the film’s restored, 197-minute “roadshow” version which contains a full 34 minutes more than other versions in circulation. Most of those 34 minutes are made up of the beginnings and endings of scenes that remain in the film’s general release, but a few previously unseen moments — such as one in which Spencer Tracy buys a long-awaited chocolate fudge sunday for himself, and plots on the phone with Buster Keaton — feel like they never should’ve been cut from the film.

What Criterion’s version really does, though, is allow a richer experience of the film than has ever been possible. The truth is that Mad, Mad World is one of those crucial, touchstone films that capture a time and a place — in this case, post-War southern California as it came to embody the American Dream.

Most movies dealing with southern California, of course, are really just about Los Angeles. But in jumping from remote locales like Idyllwild to Santa Rosa, from Twentynine Palms to San Pedro, Mad, Mad World mostly takes place on the periphery of Los Angeles, loitering in abstract, pseudo-mythic settings near the desert or the ocean — places that haven’t changed very much over the past 50 years. (This accounts for why the film hardly seems to have aged.) Indeed, Mad, Mad World isn’t really interested in Los Angeles at all, instead focusing on southern California’s “frontier” regions — remote, barely-there desert oases with quaint names like “Plaster City,'” populated by service stations straight out of an Ed Ruscha painting. It’s the landscape of Route 66, pop art and Psycho, transfigured into a comic stage suitable for the Road Runner.

It’s a wide-open, sun-dappled, candy-colored place where dreams seem like they should always come true — even when they don’t.

You feel this sort of thing in Jonathan Winters’ character, trucker Lennie Pike, the film’s working class hero who drives the Modesto to Yuma run. He’s a big, jowly bear of a man who seems like he’s spent his entire life getting screwed over — and of course he does get screwed over in the film, deliciously so, by Phil Silvers. Winters’ pent-up rage is so great that at one point he single-handedly demolishes an entire desert gas station; his California Dream is simply to wring Phil Silvers’ neck, as payback for all the slimy businessmen he’s ever come in contact with. Winters’ manic energy is so intense that every time he’s on camera, he completely owns the movie.

Since we mentioned Hitchcock above, it’s worth noting that Mad, Mad World and Psycho both share a Saul Bass opening title sequence, and both stories are motivated by stolen money. Both films also feature mother-dominated men; Mad, Mad World‘s spastic Sylvester Marcus (played by Dick Shawn) offers a kind of comic take on what Norman Bates might’ve turned out like if he’d finally escaped his mother’s house and become a skirt-chasing beach comber.

Mad, Mad World even more strongly resembles Hitchcock’s North by Northwest, with its bold, colorful, modernist lines, bravura action sequences, and big set-piece climax involving a struggle atop a huge edifice. Both films also share a Saul Bass title sequence (see Mad, Mad World‘s below), and both feature a cross-country dash in pursuit of a MacGuffin, all conducted under the benign observation of the authorities. And, once again, both films feature mother-dominated men (think of Cary Grant in North by Northwest).

While on the subject of benign observation of the authorities, it’s worth noting that the police of this era somehow manage to track Mad, Mad World‘s malefactors all over southern California without use of: the NSA, drones, surveillance cameras, full-body scanners or Google Glasses. Mostly they do it with common sense and a little basic psychology. Also, they drive normal police cars instead of armored tanks; i.e., they don’t view their fellow citizens as terrorist threats, or descend on them with SWAT teams.

Otherwise, comparisons to Hitchcock’s films seem appropriate, because Mad, Mad World similarly recycles a lot of pop-psychological ideas (derived, one suspects, from Philip Wylie’s Generation of Vipers) about what was supposedly ailing American men at that time: namely, that they’re bossed around too much by their wives, daughters, or — in the case of Mad, Mad World‘s termagant-extraordinaire, Ethel Merman — their mothers.

It’s a decidedly unchivalrous, chauvinistic view — but it probably speaks to the psychology of many post War men.

Terry-Thomas’ famous Mad, Mad World rant about America being “the most unspeakable matriarchy in the whole history of civilization” pretty much sums up the film’s retrograde attitude, although it’s hard not to laugh when he argues how bosoms “have become the dominant theme in American culture: in literature, advertising and all fields of entertainment and everything. I’ll wager you anything you like that if American women stopped wearing brassieres, your whole national economy would collapse overnight.”

Fifty years after this rant, as Kate Upton’s zero-g Sports Illustrated photoshoot melts internet servers, it’s hard to argue with Thomas’ thesis.

Matriarchy or not, Mad, Mad World‘s male characters certainly suffer from an assortment of suburban frustrations. Pill-popping Milton Berle runs the ‘Pacific Edible Seaweed Company’ in Fresno; the failure of his company has apparently reduced him to screaming in the street. Sid Caesar plays a small-time dentist named Melville, and in one of the newly discovered ‘road show’ scenes it’s implied that he’s impotent. As for the soon-to-retire Spencer Tracy, he just wants a vacation for himself and his wife and a decent pension; he can’t even get that, because a solid majority of Republicans and Democrats on the city council resent the fact that he shut down their gambling houses. The inability of these men to achieve anything in their lives only serves to supercharge their greed.

Into this miasma of male impotence strides the wonderfully brassy Ethel Merman, the only character in the film who consistently gets her way — generally by clobbering men with her handbag. The hugely entertaining Merman takes her place along with The Manchurian Candidate‘s Angela Lansbury and Mrs. Bates from Psycho as one of the truly authoritative mother figures of the era, and the abuse she takes from male characters in Mad, Mad World often seems over-the-top and misogynistic, especially considering how much she carries the film. Indeed, the only females in the film who seem to rate approval are pencil-thin, drop-dead gorgeous women in their 20s who are respectful toward their husbands.

As a result, the sexual politics of Mad, Mad World rarely rise above Rat Pack level — a little surprising coming from the director of The Defiant Ones, Inherit the Wind and Judgement at Nuremberg.

Still, Mad, Mad World‘s men certainly get their comeuppance — brutally so — at the end of the film, as they’re randomly flung across the skies of Long Beach into buildings, trees and electrical wiring, their bodies re-assembled in full-body casts by the end of the film. One gets the sense that these men probably should’ve just listened to their wives in the first place, and ignored tales of hidden treasure.

Social critique aside, Mad, Mad World features incredible, Michael Bay-scale action and stunts, and the movie revels in the kind of big, physical comedy that characterized the silent era — although here it’s on steroids. The stunt and visual effects team of Mad, Mad World reads like a who’s-who, with Carey Loftin (Bullitt, The French Connection) handling stunt driving, and with the once-in-a-lifetime teaming of visual effects masters Linwood Dunn (Citizen Kane, Star Trek), Willis O’Brien & Marcel Delgado (King Kong), Farciot Edouart (Vertigo) and a young Jim Danforth (Clash of the Titans).

So does this Criterion edition lack anything? Only one addition would’ve made the set perfect: inclusion of the 1991 documentary Something a Little Less Serious on the making of the film, featuring extensive interviews with the film’s cast and crew. Still, if you love this film, you’ve got to own Criterion’s magnificent restoration of this landmark classic.

An equal thanks here is due to the TCM Classic Film Festival for screening the film and bringing together the cast at the Cinerama Dome. It was an unforgettable experience for any fan of classic comedy — especially if you’re mad, mad, mad, mad about southern California.

(Govindini Murty, co-editor of Libertas Film Magazine and a fellow Huffington Post blogger, contributed to this article.)

Posted on March 4th, 2014 at 8:36am.

It’s a shame that publication in Huffpo seems to require a critique of a 50 year old classic movie by the lights of present day feminist political correctness. Extrapolating this trend to another 50 years in the future will require old movies be censored due to the depiction of animal flesh consumption or positive takes on the well off in a world filled with crushing poverty.

That’s a little conspiratorial, K, don’t you think? I can assure you that nobody at HuffPost spent their Oscar weekend giving me notes on how to review the DVD release of a 50 year-old comedy. They’re a little busy over there for that.

As far as the ‘feminist political correctness’ stuff, I guess you’re one of those guys who thinks ‘uppity’ gals like Maggie Thatcher and Ayn Rand should’ve just stayed in the kitchen, eh? After all, they weren’t behaving according to the standards of their time.