[Editor’s Note: The post below appears today at The Huffington Post.]

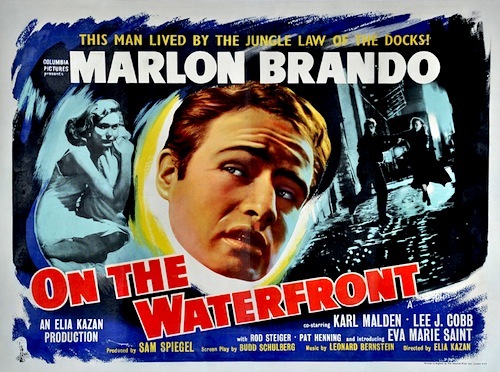

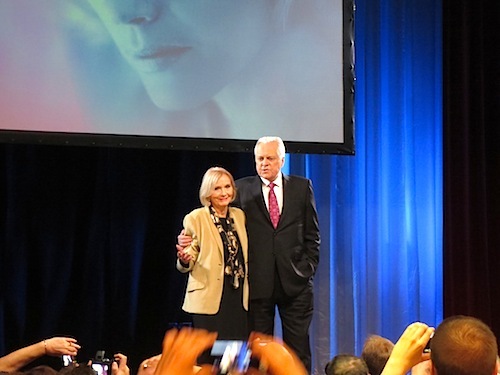

By Govindini Murty & Jason Apuzzo. This year marks the 60th Anniversary of On the Waterfront, the winner of the Best Picture Oscar for 1954. In honor of this weekend’s Oscars, we’re taking a look at what still makes this film such a timeless classic. We had the pleasure of seeing On the Waterfront last year at the TCM Classic Film Festival with star Eva Marie Saint in attendance. It was truly a delight to hear the lovely Ms. Saint talk in person about working with such brilliant talents as Marlon Brando, Elia Kazan, and Karl Malden – and the full interview featuring Ms. Saint’s discussion with Robert Osborne, followed by screenings of three of her films, including On the Waterfront, will air March 31, 2014 on TCM.

For those unfamiliar with the film, On the Waterfront tells the story of Terry Malloy (Brando), an ex-boxer turned longshoreman who struggles with his conscience when a criminal investigation into waterfront crime puts him at odds with a corrupt union boss (Lee J. Cobb) and his own brother (Rod Steiger). Inspired by a tough local priest (Karl Malden), and stirred by a touching, guilt-ridden love affair with Edie Doyle (Eva Marie Saint), Terry eventually turns away from his complicity in waterfront crime and sparks a labor revolt against the corrupt boss.

Embraced by both audiences and critics, the gritty and emotional film was nominated for 12 Academy Awards – eventually winning eight, including the Oscars for Best Picture, Best Actor (Brando), Best Supporting Actress (Saint) and Best Director (Kazan).

Filmed documentary-style in bitter cold on location at the Hoboken docks, On the Waterfront exhibits the kind of earthy realism that many studio-bound productions of the 1950s avoided. As Kazan noted in his autobiography, “[t]he bite of the wind and the temperature did a great thing for the actors’ faces: It made them look like people, not actors – in fact, like people who lived in Hoboken and suffered the cold because they had no choice.”

The film further created a sensation due to parallels between Terry Malloy’s testimony before the film’s waterfront crime commission and Elia Kazan’s controversial appearance before the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) in 1952, during which he’d been pressured to ‘name names’ of estranged former colleagues alleged to have been communists. Indeed, On the Waterfront in its day not only became a gritty poem of the American working class, but also Kazan’s plea against conformity – both of the communist and McCarthyite variety.

Whatever one thinks of Kazan’s questionable behavior – the true motivation of which remains obscure – the artistry of his film has never been in doubt. Indeed, controversies over the film’s politics have abated in the sixty years since On the Waterfront‘s release, and what remains today is a stark, austere, almost religious masterpiece that derives its strength from the honesty of its emotions – unencumbered by the usual Hollywood trappings of celebrity narcissism, violent action or visual effects.

Indeed, seeing On the Waterfront on the Chinese Theatre’s gigantic screen during the TCM Classic Film Festival reminded us again of why simple human truth in storytelling – particularly as conveyed by expressive faces in close-up – is always so compelling. On the Waterfront emerged out of the tradition of documentary realism – standing midway between the Italian Neorealism of films like Rossellini’s Rome, Open City and Fellini’s La Strada that arose out of the ashes of WWII, and the later avant-garde realism of the French New Wave films of Truffaut and Godard. On the Waterfront found the ideal, humanistic point between these two styles, and in the process created its own, uniquely American idiom – one featuring strongly defined, heroic characters, expressive film noir photography, and a poignant clash between group conformity and individual integrity.

The realism of On the Waterfront also owes much to Elia Kazan’s formative years in the Group Theatre and the Actors Studio, institutions steeped in the acting theories of the great Constantin Stanislavski. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, Stanislavski and his Moscow Art Theatre worked to portray greater human truth on stage – what he called “spiritual realism” – most famously in their productions of Chekhov’s plays. [Contrary to modern misconceptions, Stanislavski was never locked into one ‘method’ to achieve this human truth; his system used a variety of techniques to help actors access their emotions. These techniques included experiments in ’emotion memory,’ and then later what he found to be the more reliable ‘method of physical actions.’]

One sees this realist tradition achieve its cinematic pinnacle in On the Waterfront – and on the big screen (as opposed to on a TV or tablet), the movie’s depiction of elemental human conflict is transformed into almost mythic proportions, like a tragedy from the Theatre of Dionysus during Periclean Athens. Kazan’s camera never flinches in depicting concrete, specific reality – the film is populated with expressive, poignant faces like those inhabiting the Greek Orthodox churches of Kazan’s youth – but the film is nonetheless timeless in exploring the tragic-yet-hopeful experience of being human. Such a perfect fusion of realistic acting and documentary-style photography (On the Waterfront won the Oscar for best black-and-white cinematography) has arguably never been achieved before or since, except perhaps in John Ford’s The Grapes of Wrath.

Indeed, in an age of digital special effects and endless image-manipulation, it’s wonderful to see faces, characters, settings, and emotions as authentic and true as those in On the Waterfront.

Certainly the loveliest face in On the Waterfront belongs to Eva Marie Saint, who discussed her experience making the film during a wide-ranging conversation with Robert Osborne at the TCM Classic Film Festival in 2013 (the festival returns again in Hollywood this April 10th-13th). We had the pleasure of attending that event, as well as the later Chinese Theatre screening of On the Waterfront at which Saint appeared again with host Ben Mankiewicz. [Quotes of Saint’s comments below are based on our hand-written notes during those events. To see the full conversations, with Saint’s charming recollections on acting opposite Cary Grant in Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest, or opposite Paul Newman in Otto Preminger’s Exodus and in other classic films, be sure to watch the special when it airs on TCM.]

During the conversation with Osborne, Saint talked about joining the Actors Studio shortly after her arrival in New York and how important this was to her: “That’s where I learned to use my instrument and have confidence in what I have … and to work and work and work with terrific actors … Brando was there, Eli Wallach, Kazan the director, they were all starting out.”

Another pivotal early experience for Saint was being cast in a stage production of The Trip to Bountiful with Lillian Gish. Saint explained: “Lillian Gish was another mentor in my life, my husband is another – (and, she adds with a twinkle) – so is Robert Osborne.”

Kazan saw Saint on the stage and cast her in On the Waterfront. Saint described how when she was cast in the film, she would leave her home in New York in the morning, go to the film set in Hoboken, come home, get dinner for her husband (which she still does), and then act in the play at night. Saint said of the first day of the film’s shoot, “I cried as I left the house … I didn’t know what to expect. My husband told me, ‘It’s Elia Kazan, Brando’s there, you’ll be fine.'” Saint adds, “I never worked with another director like Kazan. I think he was my favorite.” She recounted of Kazan’s directing style: “Kazan was very quiet, he would come up to you and whisper directions in your ear.”

When Osborne asked her what she thought of Marlon Brando, Saint said, after a big smile and a dramatic pause: “He was adorable, but a little frightening … you felt he could see right through you.” She added, “he gave every line reading differently, so that it was always new.” Saint describes her first day on the set, “I was nervous the first day. My first scene was up on the rooftop with the pigeons” opposite Brando. Kazan came up to her and told her quietly, “This is the first time you are up there with a strange man on a roof top … I want you to pretend there’s a wild animal that could come out at any time.”

Such advice apparently worked, for Saint went on to win the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress. Saint described her excitement at winning the Oscar, noting that she said in her acceptance speech, “Thank you, I’m so excited, I think I’m going to have my baby!” And, Saint added, she had her baby just two days later.

After discussing her other roles in films like Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest, Raintree County (with Elizabeth Taylor and Montgomery Clift), Exodus, and Grand Prix (with James Garner and Yves Montand), Saint wrapped up the conversation with a wonderful bit of wisdom. Saint (who currently appears in Winter’s Tale) explained what it is that draws her to a script today: she looks for a role where “someone changes, where there’s a character who’s interesting.” Saint added this crucial point: “The thing for me is, the longer you live, the smarter you get … and hopefully that makes you a better actress … because people are interesting.”

As Hollywood gathers this weekend to celebrate the Oscars and commemorate another year in American cinema, this thought comes to mind: our movies, with their enormous budgets, elaborate special effects, and minute attention to external detail have never had such gorgeous and gilded surfaces as they have today – but isn’t it time we made an equal effort to authentically depict the inner lives of human beings, as well? This, surely, is where On the Waterfront still seems as powerful today as it was 60 years ago.

Insight into human behavior – in all its turbulence, conflict and complexity – is still the prerequisite for good storytelling, an important thing to remember as Hollywood gathers this weekend to once again honor its best.

Posted on March 2nd, 2014 at 3:47pm.