[Editor’s Note: The post below appears today on the front page of The Huffington Post.]

By Govindini Murty. When The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo hits movie theaters on December 21st, it will be the second major female-led franchise movie released in just over a month. The first, The Twilight Saga: Breaking Dawn – Part I, has already earned over $640 million dollars worldwide since its November 18th release and has become the third-highest grossing movie of 2011 (after Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2 and Transformers: Dark of the Moon – and on a lower budget than those films). The remarkable success of the Twilight film series, with over $2 billion in worldwide ticket sales to date, proves that audiences will show up to see tentpole movies built around women. Now with the upcoming release of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and the spring/summer 2012 openings of Mirror Mirror, The Hunger Games, and Snow White and the Huntsman, audiences are being offered a run of female-oriented big-budget films unlike anything they’ve seen in recent years. After decades of lavishing resources on male-led action and comic book movies, Hollywood is finally making an effort to give women and their stories the blockbuster treatment.

In doing so, the film industry is hearkening back to what was once a strength of classic Hollywood: the blockbuster women’s film. Such films were high-quality productions that elevated the unique psychology, heroism and romance of women’s lives to the level of epic entertainment. The great era of this kind of women’s film was in the ’30s and ’40s when movies like Greta Garbo’s Queen Christina, Vivien Leigh’s Gone with the Wind, Marlene Dietrich’s The Scarlet Empress, Joan Crawford’s Mildred Pierce, Greer Garson’s Mrs. Miniver, and Bette Davis’ Jezebel enthralled audiences. Whether they told historical or contemporary stories, such films offered a ‘blockbuster’ vision of women’s lives – both in terms of the resources the studios devoted to them (A-list directors and casts, big budgets) as well as in the importance they placed in their heroine’s emotional journeys. Such films were a mainstay of classic Hollywood, filling box office coffers and building the careers of talented actresses. Further, these films inspired both women and men, for they successfully transformed the unique emotions and experiences of women into works of art with universal significance.

The success of classic women-led films is reflected in their status as some of the highest grossing films of all time. According to Box Office Mojo’s list of the all time highest grossing films (all figures are domestic, adjusted for inflation), Gone with the Wind (1939) is still number one with an astonishing U.S. theatrical total of $1.6 billion dollars. The Sound of Music ($1.13 billion), Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs ($867 million), and Titanic ($1.02 billion) also figure in the top ten list – and one could argue that Dr. Zhivago ($988 million) and The Exorcist ($880 million) owe much of their success to their strong female characters, as well. The success of these films shows that women and their stories have been a compelling draw in many of the biggest movies ever made.

Starting in the 1970s and 1980s, however, the action movie rose in prominence – and a genre that naturally favors men over women took over Hollywood. The success of the male-oriented action film was used to justify spending less money on women’s films, and women were increasingly relegated to lower budget romantic comedies and dramas. This led to a vicious cycle in which the modest budgets given to women’s films led to modest box office returns that were then used as an excuse to spend even less on women’s films – completely contradicting the evidence of the successful women’s films of the classic Hollywood era. While some fine movies were made in this period – Norma Rae, Julia, An Unmarried Woman – much of the heroism, glamor, and romance that had characterized the great women’s films of the ’30s and ’40s was lost.

There was a brief resurgence of the blockbuster women’s film in the ’80s with Out of Africa, Terms of Endearment, and comedies like Romancing the Stone, but this promising trend petered out in the early ’90s. By the late ’90s, the film industry’s downgrading of women’s importance in the movies was such that when Titanic became a massive hit in 1997 – a film very much built around Kate Winslet and her emotional journey – the film’s success was instead credited to Leonardo DiCaprio and to the film’s special effects.

This mindset has led to another trend in contemporary Hollywood: the rise of the comic book movie. With the comic book movie, the film industry has became preoccupied with producing a never-ending stream of films based around male adolescence and coming of age. That’s fine for men, but there’s little there to relate to for women. On the rare occasion when a woman plays the lead in a big-budget comic book or video game movie – say Angelina Jolie in the Tomb Raider films, or Milla Jovovich in the Resident Evil films – her role is little different from that of a man. This is a shame because women are capable of a lot more on the big screen than simply wielding violence.

Women’s life experiences are different from those of men. We wish to be leaders and to achieve success in the world, but in our entertainment we also want romance, adventure, and emotional catharsis. When the Twilight movies came along, they answered this need beautifully. Twilight‘s highly traditional storyline of a young woman falling in love with and taming a dangerous man has appealed to women for generations and dates back to the 19th century Gothic novel and beyond (as I describe in my analysis of the literary and mythological themes in the Twilight series). One sees this storyline in everything from the fable of Beauty and the Beast to novels like Jane Eyre and Gone with the Wind. Ultimately, this storyline serves as a metaphor for a woman’s heroic quest to overcome the forces of evil and find love and fulfillment in the world.

Thus, the entire focus of Twilight is on the emotional journey of Bella Swan and not the physical action (although there is action in the film). Though I find it hard to identify with Bella’s lack of career ambition, the single-mindedness of her determination to romance Edward Cullen in the face of widespread disapproval (and despite the fact that he is a vampire) demonstrates a feisty and independent spirit. This is the real ‘action’ of the film – not the external violence, but the internal drama – and this is what has proven so immensely appealing to millions of women. After all, how much action is there really in Breaking Dawn – Part I? The first half hour of the film is spent lingering on Bella’s wedding, while the second half of the film features Bella lying pregnant on a couch – with a brief honeymoon in Brazil in between, and a few scenes involving werewolves. And yet the movie has so far made over $640 million worldwide.

While the success of Twilight may be surprising to some, women’s lives and their emotional journeys have been the stuff of successful storytelling for millennia. For example, the rivalry of the goddesses Hera, Athena and Aphrodite plays a central role in the events of The Iliad, while the touching portrayal of Penelope’s honor and fortitude forms the emotional backbone of The Odyssey. The extraordinary depiction of Medea’s emotional journey in Apollonius of Rhodes’ Argonautica inspired the passionate figure of Queen Dido in Virgil’s Aeneid, which in turn influenced generations of storytellers. Fast-forwarding over a millennia, women’s lives and their complex characters figured in the birth of the modern novel, from Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa to Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, and Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway. Even in Asia, the Japanese literary tradition was born in the work of female writers of the 10th – 11th centuries AD who explored women’s lives in poignant masterpieces like Lady Murasaki’s The Tale of Genji and Sei Shonagon’s The Pillow Book.

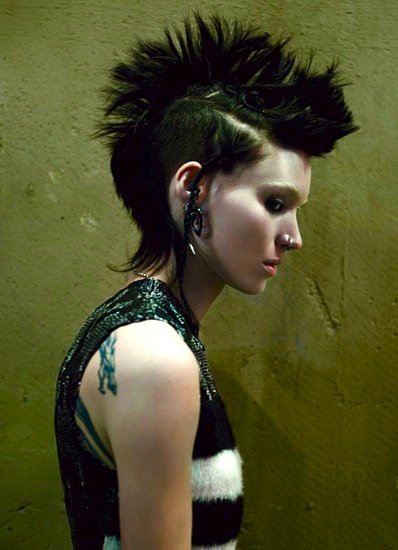

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and The Hunger Games trilogies are being turned into major movie franchises because they too offer something more than simply action or violence in their portrayals of women. The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo gives us a central character, Lisbeth Salander, who is fascinating both for her psychological complexity and her intelligence. The Hunger Games is compelling because its heroine, Katniss Everdeen, has to learn how to negotiate complex rivalries in order to stay alive in the games. In the upcoming Snow White adaptations Mirror Mirror and Snow White and the Huntsman, the heroines are forced to confront the deadly jealousy and vanity of a wicked queen. Although there is action in all these films, it is the emotional journeys of the women involved that will likely be the main draw.

This is what forms the core similarity between the contemporary women’s blockbuster films of today and the great women’s films of the classic Hollywood era. Whether it be The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo or Mildred Pierce, these movies depict their female leads dealing with the central issues of love, friendship, betrayal, and ambition that women everywhere have to deal with in their own lives.

By lavishing big budgets on these women’s movies, Hollywood is acknowledging that women’s stories are worthy of being told on the grand scale. Epic roles in epic films give women the chance to exhibit crucial qualities – our potential for leadership, our capacity for honor, love, intelligence, and nobility. Such films also give men the opportunity to relate to women’s stories as if they were their own. It’s the least the movies can do to reflect the dramatic and consequential lives women are living today and have lived throughout history.

Posted on December 20th, 2011 at 10:00am.

I’m looking forward to Libertas’s review of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. I caught it last night and there’s some interesting differences from the original and a growing & disturbing trend in today’s Hollywood. To saw the least, Daniel Craig is no Clark Gable. And to borrow from the theme of The National Review’s review of The Desendant’s “the emergence of the beta male.”

johngaltjkt – Joe Bendel’s review of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo is going up today, so be sure to check it out! I’m really busy right now but I’m going to try to see the film in the next few days and will let you all know my take on it. As for Hollywood and the promotion of passive men, don’t even get me started …

Great post. I got to do some research on the script development for Jezebel at the USC library while in grad school. I read all the different versions, saw notes from producers and writers. They were all dealing with the issues you mentioned above.

Thanks so much Patricia! That must have been wonderful to do research like that into “Jezebel.” That’s something I’ve always wanted to do – sift through some of the excellent film archives we have here in LA and research the creation of some of our classic films. You’ll have to tell us more some time about what you found out about “Jezebel” and how classic Hollywood created such superb women’s films. 🙂

Thank goddess there is a venue where these kind of views can finally be shared.

Also, Hollywood should do more to celebrate people of color!