[Editor’s Note: the post below appears today on the front page of The Huffington Post.]

By Govindini Murty. A pair of new films this week offers a critique of capitalism sure to gladden the heart of any Occupy Wall Street protester. This weekend’s Tower Heist depicts a group of employees who plot to rob a Madoff-style financier who cheated them, while the new sci-fi film In Time portrays a dystopian future in which time is literally money.

In Time in particular implies that time and nature are sources of tyranny equivalent to the capitalist system. The film depicts its hero, Justin Timberlake, as a proletarian Prometheus who robs the financial gods in order to redistribute their ill-gotten gains to an oppressed humanity. In In Time‘s near-future dystopia, human beings have been genetically-engineered to stop aging at 25, after which biological ‘clocks’ on their arms determine how long they have to live. Time on these clocks is spent like currency; people pay with hours or days of their lives for everything from a cup of coffee to their monthly rent. The wealthy store up hundreds if not thousands of extra years, while the poor live with only a few extra hours at any time. If they run out of time before they can earn more, the clock runs down to zero and they die.

Will Salas (Justin Timberlake), a young man from the ghetto, teams up with Sylvia Weis (Amanda Seyfried) – the disaffected daughter of wealthy banker Philippe Weis – to rob her father’s time banks and redistribute the time stored there to the poor. They justify this by telling themselves “it isn’t stealing if it is already stolen.” And given the exaggeratedly cruel and unjust world that In Time portrays, who could disagree?

In its desire to equate time with money and denounce capitalism, however, In Time ignores the basic fact that in the real world money is malleable, time is not. Money can be earned, stored up, and passed on to others; by providing a portable form of wealth, it frees people from the barter system and feudal economies of centuries past when human beings were tied to the land like slaves. In short, money offers us a chance at freedom and self-sufficiency, depending on one’s willingness to work and the opportunities one is given.

We have no such chance with time. Time is the ultimate leveler, flowing over all equally and waiting for no-one, whether they be rich or poor, young or old. No matter how hard one works or how healthy one may be, there is no surefire way to increase one’s time nor determine in advance how much time one may have.

As the Roman Stoic philosopher Seneca said of time in his famous essay On the Shortness of Life:

“It will not lengthen itself for a king’s command or a people’s favour. As it started out on its first day, so it will run on, nowhere pausing or turning aside.” (Trans. C.D.N. Costa)

The limits of time and human mortality have been subjects of some of our greatest science-fiction films. Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 contrasts the brevity of human existence with the vastness of time, as represented by the alien monoliths. In Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris, the hero is tormented by the ‘eternal recurrence’ of his beloved who continually returns to him and is lost again to a time-bending cosmic ocean. In Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, artificial human ‘replicants’ are granted only a few years to live. As the character Roy Batty poignantly says of the brief, vivid life he experiences as a replicant: “All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in the rain.”

Such films depict the tragedy of a human consciousness that is aware of the brevity of its own existence, and of the vastness of time that threatens to overwhelm it.

In Time isn’t interested in any of this. It crassly defines time as a commercial conspiracy imposed from above, which is also how the film defines the capitalist system. In Time rails against life’s limits and proposes that they can be overcome by ameliorative acts like robbing banks. According to the film, all people who have excess ‘time’ (i.e., money) must have stolen it. No-one is capable of earning it honestly. Banks, businesses, the millions of average people who work hard and have savings accounts – all are ultimately thieves. In combatting this thievery, the film advocates the redistribution of wealth – an easy, political answer to intractable existential questions. Ironically, of course, the Hollywood millionaires who make films like In Time and the capitalists-as-thieves comedy Tower Heist make no effort to redistribute their own fortunes – or to make their films available for free to the public.

Movies like In Time and Tower Heist offer simplistic solutions to the problem of inequality. The limits of time, and the inequality with which nature grants human beings varying degrees of talent, intelligence, beauty, strength, or luck, are tragedies every human being must confront. We can mitigate them with compassion, and work for greater equality of opportunity – but we are not gods and we cannot determine equality of outcome.

Posted on November 6th, 2011 at 1:10pm.

Advocates of redistributive systems are eternally confident that they will be the beneficiaries of the redistribution they propose, rather than the mules. History says otherwise. Perhaps for a brief time the many can live off of the efforts of the few, but not for long. Then they are in for a rude awakening. Of course by then it will already be too late.

Yes, that’s a good point. What they never take into account is the effect that the redistribution will have on any future desire for productivity or innovation. You can’t have a society that functions if people are in effect punished for their hard work and success. That said, there will always be those exceptions of people who become wealthy either through luck or through criminal activity – if it’s the former, that’s the price of living in a free market system – if it’s the latter, we have a justice system to take care of that.

I agree with most of what you say, however, and I’ll come out and say I haven’t seen ethier of these movies, but it seems to me at least that what both In Time and Tower Heist have in common is a sense of an injustice being ether ignored or aided by the system. ie. In Time has people living to 25 then having their remaining lifespan limited by how much time they have considering that the average lifespan is closer to 80 the vast majority of people in this world have had 60 years of their life stolen from them. The villian of Tower Heist is of course runnning a Ponzi scheme. Both movies have your average blue collar guys fighting back Robin Hood style against the man (Tower Heist) or system (In Time) that has cheated them and have got away with it. In a sense these films are the modern equivalent of “Death Wish” with your average person taking action against the injustice in the world street level or orginized crime in Death Wishes day, White Collar criminals in Tower Heist/In Time. There essentially a fantasy about achieving a sense of justice that has been denied in the real world, like the sentiment that something was wrong with the justice system in Death Wish’s day, there is a widespread sentiment that there’s something wrong with are financial/economic system. That’s not to say that the ideals behind that system are evil or wrong, but that a problem exists in how those ideals are being implemented and might need to be examinded.

Jim – I think if you saw the films you would see that they go beyond portraying the righting of injustice and are actually implying a far broader critique of the capitalist system. This is really taken to an extreme in “In Time,” when they literally say that anyone with money in a bank must have stolen it. Every time the hero and heroine rob a bank in the movie to redistribute the money to the poor, they say “It isn’t stealing if it’s already stolen” – which implies that everyone with money in that bank must have stolen it – including presumably many middle class people and working class people. It’s the very idea of capitalism they object to.

Haven’t seen either movie, don’t intend to. I will ask one question though, How as the decision to stop every one from aging at 25 decide upon, how was it implemented and how was the system for additional time arrived at? I’m thinking that the system was supposed to be an attempt to keep everyone gainfully employed, as opposed to simply becoming social parasites.

any misspellings are due to my fingers being faster than my computer.

I saw Tower Heist and the best I can say is that it’s not dreadful because it had the steady professional hand of Brett Ratner directing.

What these movies have in common is Hollywood’s infantile/dangerous view of capitalism. Hollywood always fails to provide a real view that displays the benefit of our system that allows ordinary people to achieve extraordinary things. Could there been a Apple? A Microsoft? Without our system of venture capitalist? Will We ever see the like again in our lifetime considering our current political climate? Govindini, you’d probably agree with me that another particularly egregious movie was this past summers Planet of the Apes. Among it’s many crimes of human societal defamation was also an American societal defamation, against greedy venture capitalist. It’s scary times We live in because We should pull together in order weather this storm however certain elements are looking to “You never let a serious crisis go to waste.”

You make great points. The extraordinary information revolution created and sustained by Silicon Vally shows what the free market and individual initiative can do. How much value in the world – how many hundreds of thousands of jobs – have been created by the individuals behind Apple, Microsoft, Google, IBM, Hewlett Packard, Ebay, Paypal, et al? What always gets me is the the very people who denounce capitalism are happy to use all its products. As for “Rise of Planet of the Apes,” it was beyond vile. Not only did it denigrate venture capitalists and pharmaceutical companies (the same companies making the drugs that are lengthening people’s lives), but they also portray apes as preferable to humans. It’s anti-capitalism and misanthropy at its worst.

But you know what? If we want to make a difference, we need to make more movies ourselves that convey a free-market viewpoint.

Great editorial, Govindini — fantastic job.

I saw “In Time” last night, and I have to say that I really enjoyed it, but it wasn’t nearly enough of a science-fiction piece to completely resonate with me. The film was obviously obsessed with its worldview, but I don’t think it had the guts to come out and be full-blown Marxist propaganda.

The antagonists in the film were just too ambiguous. It’s almost as if the creators didn’t have the guts to go all the way with it. During the film, I just kept thinking of Bill Clinton and his relationship with Citigroup, which dictated a lot of policy. The government marriage with banks in the Community Reinvestment Act, or the student loan takeover, or the Dodd/Frank stuff, or all the banks that are in bed with the Obama administration … that all came to mind.

There’s one gigantic fact that leftists never want to admit, or just don’t know: The smallest bit of government intervention ALWAYS invites cronyism. It’s regulation that actually skews matters, and creates a system where winners and losers are chosen.

Can corporations and bankers be evil? Absolutely … but they become that way when they get involved with the government. Besides, the Wall Street guys never create anything. Yes, in a perfect world, they help put people with goods and services together, and aid growth, but they’re not capitalists in the the true entrepreneurial sense.

The best political sales jobs are not “on the nose” or heavy handed. If they avoided “going all the way” it’s more likely to be a sign they know what they understand that. With the left in control of all but a fraction of the media, It’s not necessary to score one or two big hits, they know there’s going to be numerous small advocacy pieces coming up.

That’s a great point, K. I was actually going to include something like that, but you said it better than than what I considered writing.

You’re also right to point out the left’s power, which resides in their control of “all but a fraction of the media” as you put it.

I don’t know if common-sense people will ever be able to counter that head-on, so my suggestion is to let deny them that power — neutralize it. So often, we give them power with mere resistance, which makes them — and their lies and half-truths — grow.

In this case, if indeed the filmmakers are making an argument against Wall Street and banks, then maybe some should respond by saying “absolutely … the unholy marriage of government and business creates this monster – that’s a great lesson the film show.”

I guarantee that would do a great deal to shut them up — or at least change the debate, which will then be in the favor of common-sense people who favor logic and facts over emotion.

That’s a good point K – these movies would have been far more effective if they hadn’t felt the need to bludgeon their ideological point home. I think the fact that both “In Time” and “Tower Heist” performed below expectations shows that the public may have sensed that.

Vince – thanks so much for your comment! I’m having fun with this new opportunity to blog at HuffPost and am enjoying all the interactions.

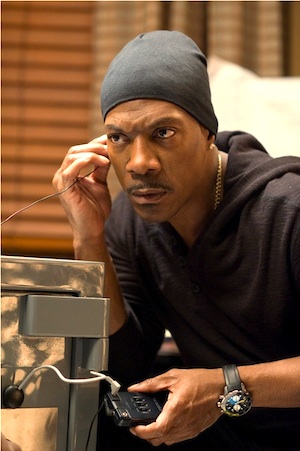

As for “In Time,” I really thought it had potential to be a much better movie. I liked the visual style of the film, I thought Justin Timberlake was convincing as a proletarian hero who uses his smarts to succeed in the world of wealth and privilege, etc.

As you say though, it wasn’t nearly enough of a sci-fi piece to be really interesting, and it made such a strenuous effort to make political points and draw real-world parallels (ultimately, faulty real-world parallels) that it took away from the story-telling of the film.

And that’s a great point about how government interference leads to cronyism by artificially-picking winners and losers. It didn’t work in the Soviet Union (one thinks of the systematic corruption and massive shortages and inefficiencies of government controlled industry), and it doesn’t work here.

Based on the Harlan Ellison lawsuit alone, it would seem that the “In Time” creators also believed some people have too many “creative minutes” which must be redistributed to those who don’t have enough.