[Editor’s Note: This post appears today at The Huffington Post and at AOL-Moviefone.]

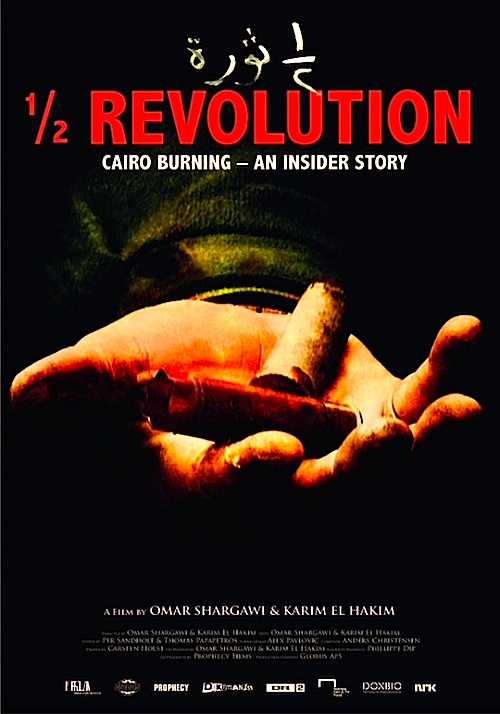

By Govindini Murty. As the Egyptian military government prepares to put nineteen American employees of pro-democracy NGOs on trial, and thousands of Egyptians continue to demonstrate over the stalling of democratic reforms, the new documentary 1/2 Revolution offers a striking look back at the Egyptian revolution of one year ago.

Premiering recently at the 2012 Sundance Film Festival, 1/2 Revolution depicts the revolution through the eyes of a group of Egyptian activists directly involved in it. Using cell phone cameras and hand-held camcorders, the filmmaker-activists capture dramatic footage of clashes between average Egyptians calling for freedom and the repressive government forces attempting to stop them.

As co-director Karim El Hakim said after the film’s recent Sundance screening, “You can’t get any more cinema verité than this.”

Danish-Palestinian director Omar Shargawi and Egyptian-American director Karim El Hakim live with their families just a few blocks from Tahrir Square in Cairo. When hundreds of thousands of Egyptians take to the streets on January 25th, 2011 to demand the ouster of dictator Hosni Mubarak, Omar and Karim head down from their apartments to record the events. Viewers are immediately thrown into the visceral experience of the revolution. Crowds of protesters run through the streets shouting “Egypt! Egypt! “Join us! Join us!” “Freedom! Freedom!” When gangs of government-paid thugs and police start beating and shooting the protesters, the protesters shout “No violence! No violence!” This call to non-violence is one of the early strong points of the documentary. To emphasize the theme, Shargawi points out a crowd of demonstrators who surround a group of police yet refrain from assaulting them.

Danish-Palestinian director Omar Shargawi and Egyptian-American director Karim El Hakim live with their families just a few blocks from Tahrir Square in Cairo. When hundreds of thousands of Egyptians take to the streets on January 25th, 2011 to demand the ouster of dictator Hosni Mubarak, Omar and Karim head down from their apartments to record the events. Viewers are immediately thrown into the visceral experience of the revolution. Crowds of protesters run through the streets shouting “Egypt! Egypt! “Join us! Join us!” “Freedom! Freedom!” When gangs of government-paid thugs and police start beating and shooting the protesters, the protesters shout “No violence! No violence!” This call to non-violence is one of the early strong points of the documentary. To emphasize the theme, Shargawi points out a crowd of demonstrators who surround a group of police yet refrain from assaulting them.

Over time, though, these commendable calls to non-violence are drowned out by the tide of chaos and bloodshed that overtakes the demonstrations when the government attacks. Police fire into the roiling crowds of protesters with live ammunition, loud booms announce the launching of tear gas canisters through the air, and demonstrators and counter-demonstrators fight back and forth with truncheons, rocks, and knives. Demanding to see their passports, secret police harass Karim and Omar as they attempt to film the events, and Omar pulls a scarf around his face to disguise his identity.

Later, Karim is gassed in the face and stumbles home partially blinded, while Omar is severally beaten in a dark alley, barely emerging alive. Government snipers start shooting people through the windows of their apartments in the blocks around Tahrir Square – making viewers fear for the safety of the filmmakers in their own homes, particularly as one of them has a baby who keeps wandering close to the windows. Late in the film, government thugs even take over the street below the apartment building and start harassing the residents, which is what finally forces the filmmakers to question staying in the country.

In capturing the tumult of the Cairo protests, 1/2 Revolution depicts more violence than most Hollywood action movies – but tragically, the mayhem here is all too real.

The seemingly intractable rage captured in the film – both from democratic protesters righteously angry over the suppression of their human rights, and from entrenched government elites determined to hold on to power at any cost – highlights the central challenge facing the Egyptian people today. How will they overcome this bitterness and anger – these scars from decades of violence, repression, and authoritarian rule – in order to build a peaceful democracy?

In his seminal 1947 study of German film, From Caligari to Hitler, Siegfried Kracauer pointed out that the details of life captured in a film often reveal a country’s unconscious predilections. The details captured in 1/2 Revolution are ominous: activists repeatedly declare their willingness to die and become martyrs, the camera dwells on shattered heads and limbs, bodies on stretchers being rushed away, a man lifting up his shirt to show a bullet wound in his back, a pool of blood on the pavement with the word ‘Egypt’ traced in Arabic. Even more ominous are the anti-American and anti-Jewish symbols scrawled onto anti-Mubarak protest signs. One particularly ugly sign depicts Mubarak as the devil with pointy ears and a Star of David stamped on his forehead.

Sadly, the filmmakers and their friends engage in implicitly anti-Israeli rhetoric themselves. Co-director Omar Shargawi, whose father is Palestinian, says with pride of the demonstrations, “It was like being part of the intifada or something.” One of his friends, a woman also of Palestinian origin, expresses fears that “the Israeli army is massing at the border” and worries that the U.S. might invade. Given that Israel’s population of only 7.8 million is vastly outnumbered by Egypt’s population of 81 million, and given that the American government was generally supportive of the Egyptian revolution, these kind of fears come across as over the top. But this is the dark side of the revolution: the urge to look for blame in outside bogey-men – in this case, America and Israel – rather than look internally to ask why so many Arab states have failed to achieve lasting democracy.

This urge to scapegoat outsiders is having serious consequences. The AP reported on Sunday that the Egyptian military government, after raiding a number of American, German, and Egyptian pro-democracy NGOs in December of 2011, is now planning to put forty-three employees of these NGOs, including nineteen Americans, on criminal trial. One of these nineteen Americans is Sam LaHood, the son of U.S. Secretary of Transportation Ray LaHood. Both President Obama and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton have made appeals to the Egyptian government, to no avail. As the AP reports:

“The generals who took power after Mr. Mubarak’s fall have accused ‘foreign hands’ of being behind protests against their rule and frequently depict the protesters as receiving funds from abroad in a plot to destabilize the country. Those allegations have cost the youth activists that spearheaded Mr. Mubarak’s ouster support among a wider public that is sensitive to allegations of foreign meddling and sees a conspiracy to destabilize Egypt in nearly every move by a foreign nation.”

The Egyptians who fall for such xenophobic rhetoric simply play into the hands of the military and government elites who wish to deflect blame away from their own failure to achieve prosperity and freedom for Egypt. Rather than blame America, Israel, or foreign NGOs for their troubles, Egyptians might ask themselves why a third of their public is still illiterate (according to the UNDP, Egypt ranks #156 worldwide in literacy, below even Angola and the Congo). Or they might ask themselves why over 90% of Egyptians lack basic property rights – keeping their economy in a condition that economist Hernando de Soto describes as “Egypt’s economic apartheid.” Egyptians might also ask themselves why they rank low in women’s rights, with the World Health Organization reporting that 91.1% of Egyptian women are subjected to the brutal practice of genital mutilation. These are some of the true social and economic injustices that hold back Egypt – despite its long and proud history – from joining the first ranks of democratic nations.

1/2 Revolution offers the rudiments of such a critique, with the documentary showing how the revolutionaries were let down by Egypt’s military even in the early days of the protests. When the police fire on the protesters in the film, the filmmakers and their friends naively hope that the army will save them. They say to each other: “The people love the army. They’re waiting for them to come.” Army tanks are shown rolling in and the filmmakers go down to talk to the soldiers and ask if they will help the revolution – only to be rebuffed. They’re even more bitterly disappointed when a line of army tanks drives into a crowd and rolls over five demonstrators, killing them.

A year later, of course, with the military now leading Egypt’s government after the resignation of Mubarak, the protesters view the army as Egypt’s new villains. Democracy activists are justly angry at the military for subjecting thousands of civilian protesters to military trials, and many Egyptians blame the military for the deadly soccer riots last week that killed 74 Egyptians and led to thousands of Egyptians taking to the streets in protest.

Interestingly, the filmmakers express the same lack of concern about Islamic radicalism today that they did about the military a year ago. One hopes that they will not be similarly disappointed. At the recent Sundance screening of 1/2 Revolution, I asked co-directors Karim El Hakim and Omar Shargawi if they were concerned that the Muslim Brotherhood and other Islamist parties had won approximately 75% of the seats in Egypt’s new parliament while secular liberals had won only about 20%, and that attacks on women and religious minorities (in particular Coptic Christians) were on the rise. El Hakim answered: “Those elements were all there before in Egypt, but they were united in opposing Mubarak, now with Mubarak gone they’re divided. This is going to be a long struggle to achieve democracy in Egypt.” As for the rise in attacks on women and religious minorities, El Hakim urged me not to believe the media, saying “Those attacks were not carried out by the Muslim Brotherhood, but by secret police paid by pro-Mubarak elements in the government trying to create dissension amongst the public.”

To their credit, the filmmakers also rejected the idea that Egypt should turn to socialism for answers. In one of the more amusing exchanges of the Sundance screening, an impassioned audience member informed the filmmakers that she too was trying to incite a revolution in America. Co-Director Karim El Hakim asked her “What kind of revolution?” – to which she answered, “a communist revolution.” There was an awkward silence, followed by a few guffaws and no cheers. El Hakim responded: “The Egyptian state was based in socialism for decades [from the ’50s through the early ’70s]; it was allied with the Soviet Union and received major funding from the KGB. This laid the basis for many of Egypt’s modern problems. Socialism is outmoded and Egypt does not need to go back to it.”

While raising a host of questions that are as yet difficult to answer, 1/2 Revolution nonetheless offers a visceral, first-hand look at the Egyptian revolution, showing how chaotic and complex the situation on the ground really is. As the filmmakers make clear, the documentary depicts one slice of the revolution, and does not attempt to offer a complete picture of the events. Nonetheless, the raw immediacy of the footage shows once again the powerful role that digital video and new media are playing in allowing democracy activists to circumvent authoritarian governments in the Middle East and advance freedom.

While one may not agree with every view held by these activists, we can all hope that they overcome the many divisions in their society to achieve a truly peaceful and democratic Egypt. Egypt has an ancient and noble heritage that is one of the foundations of the Western tradition. Egyptian history is our history, and Egypt’s people should be able to live in the same freedom we in the West do.

As Karim El Hakim said at the screening, “We Egyptians take pride in being the oldest nation in the world, but we lived in stasis for many years. Now we can finally feel a change happening … Egypt’s spirit is high, even if the country is low.”

Posted on February 7th, 2012 at 12:17pm.

That’s a very well-researched piece, Govindini. It’s good to see someone try to approach the fact that the Egyptian people will probably be in worse conditions. I still get the feeling this picture asks more questions than comes up with answers. The lazy attitude toward your question about the Islamist parties encroaching on the government is especially troubling.

I was reminded of a quote from Thomas Jefferson ion Islam:

“The ambassador answered us that [the right] was founded on the Laws of the Prophet, that it was written in their Koran, that all nations who should not have answered their authority were sinners, that it was their right and duty to make war upon them wherever they could be found, and to make slaves of all they could take as prisoners, and that every Mussulman who should be slain in battle was sure to go to Paradise.”

Of course we don’t need Jefferson to tell us that, but it’s nice to see the father of the republic that was given to us speak so eloquently on the topic.

Also, Govindini … the 19 Americans aren’t such big friends of liberty — or even democracy, for that matter. Sam LaHood, son of Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood is an Arab Spring, Hezbollah supporter, and overall raging anti-Semite — like his old man.

“I hate being right all the time.”

One of my favorite lines from a movie is uttered by Jeff Goldblum in The Lost World: Jurassic Park. “I hate being right all the time.” Just as dinosaurs eat people. Thus, when you allow a political vacuum in Egypt occur don’t be shocked when extremist Islamist parties step into the void. Just as you prematurely withdraw from countries that you’ve spent the blood and treasure of the United States to secure, don’t be surprised if the same if not worse occurs. Also if you vote for police power of the state to take from others and give to you that some day they’ll come for you too. I also find this whole kerfuffle by the Catholic Church sadly predictable. What exactly did you think you were voting for? I think one big reason that the better candidates in the Republican party sat out this go around is they know that once the full impact of the healthcare law hits in 2014 Americans will become so outraged they’ll vote for anybody that’s not a Democrat.