[Editor’s Note: the post below appears today on the front page of The Huffington Post.]

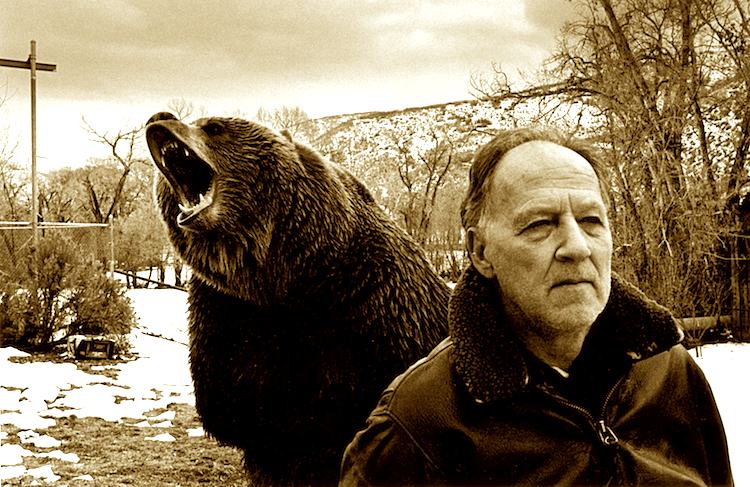

By Govindini Murty. In Part I of my interview with Werner Herzog, we discussed his new movie Into the Abyss and its searing exploration of evil in human society. Now in Part II we turn to the world of nature, which Herzog sees as even more dangerous. In Les Blanks’ documentary Burden of Dreams, Herzog famously spoke out on the “obscenity” of the jungle, its “harmony of overwhelming and collective murder.” In Herzog’s documentary Encounters at the End of the World, he expressed skepticism toward “tree huggers and whale huggers,” while in Grizzly Man, he documented the fate of a man literally killed by his unhealthy obsession with wild nature. Herzog has even criticized the romanticizing of nature in Avatar, calling the film “an abomination because of its New Age schlock and bullshit.”

Obviously Werner Herzog has strong feelings about the proper relationship between humanity and nature. One sees this, for example, in Herzog’s stunning documentary Cave of Forgotten Dreams, released this week on DVD. Cave of Forgotten Dreams offers an extraordinary look at the 30,000 – 32,000 year-old Paleolithic cave paintings inside the Chauvet Cave in southern France – currently considered to be the oldest cave paintings in the world. As Herzog told me in Part I of our discussion on the concept of “the abyss,” “I’ve always tried to look deep inside of what we are – deep into the recesses of our existence, of our prehistory – like in Cave of Forgotten Dreams. So it is some sort of a theme that runs through quite a few of my films.”

In Cave of Forgotten Dreams, Herzog speaks eloquently of the Paleolithic cave paintings of Chauvet and their relationship to the surrounding landscape:

“These images are memories of long-forgotten dreams. Is this their heartbeat, or ours? Will we ever be able to understand the vision of the artists across such an abyss of time? [Camera shows a massive natural stone arch in the landscape.] There is an aura of melodrama in this landscape. It could be straight out of a Wagner opera or a painting of German Romanticists. Could this be our connection to them? This staging of a landscape as an operatic event does not belong to the Romanticists alone. Stone Age man might have had a similar sense of inner landscapes …”

And yet despite these poetic sentiments, Herzog vehemently denies being a Romantic; rather, he defines his approach to nature as being similar to that of the artists of the late Middle Ages.

Ultimately, if one were to search for a theme that unites Werner Herzog’s diverse body of work, it would be that respect for human life and its limits is what holds us back from the brutality of amoral nature – the abyss into which humanity’s natural instincts might otherwise plunge. As Herzog told me, he is concerned above all with civilizational breakdown – with how humanity can abandon its own heights to descend into unfathomable depths of madness and annihilation. Equally importantly though, Herzog’s love of art, of literature, of joyful exploration of the world and its peoples points to a hopeful way out of the abyss and into the light of day.

Thus, in Part II of this interview, we tackle such colorful subjects as Herzog’s anti-romantic views on nature, why he can’t help ranting about Avatar, his excitement over his Rogue Film School (in which he teaches such crucial skills as “lock picking” and “neutralizing bureaucracy”), and his belief that Wrestlemania and reality TV offer vital clues to understanding civilization. The interview has been edited for length.

GM: There is this sense in all of your films, whether they’re historical dramas or contemporary documentaries, that you wish to explore the extremes. You go from examining the molecular world in scenes from Encounters at the End of the World to these broad vistas of Antarctica or the desert or the Himalayas in your other documentaries. Do you feel that you’re part of what could be termed the German Romantic tradition in terms of having this approach to nature – seeing it both as a place of danger and a place of inspiration?

WH: I think that’s a common misconception [that] I had an affinity to romantic culture – no I don’t. I do not feel much affinity with it. I don’t feel at home with it. I’m much closer to poets like Heinrich von Kleist, Georg Büchner who wrote Woyzeck – in the early 1820s he wrote literature that belonged to the early 20th century, that was almost like Expressionism. Or Hölderlin the poet, and he’s not a Romantic poet either. He’s somewhere completely unique. He’s like a continent of his own – not really comparable to other Romantic writers of his time…

And when you look at how I depict nature – wild nature for example in Grizzly Man, it’s quite evident that it’s a completely anti-Romantic view. Timothy Treadwell who was protecting bears and who was killed and eaten by a grizzly bear together with his girlfriend, he has this kind of watered down Romanticism … that’s what I’m completely against. I would stop the course of the film even and in my comment I would have an ongoing argument with Treadwell: “Here I differ from Treadwell.” I do not see wild nature as something benign and beautiful and the bears fluffy like little pets. No, they are dangerous and aggressive and nature itself looks rather chaotic and hostile. You look at the universe – it’s very, very hostile out there.

For example in Les Blanks’ Burden of Dreams I deliver a speech/rant about the jungle and you’ll never see anything so clearly against Romanticism and the romanticizing of landscapes, romanticizing of wild nature. … It’s funny because being a German everyone immediately thinks yeah yeah he must have an affinity with Romantic culture. No, I don’t.

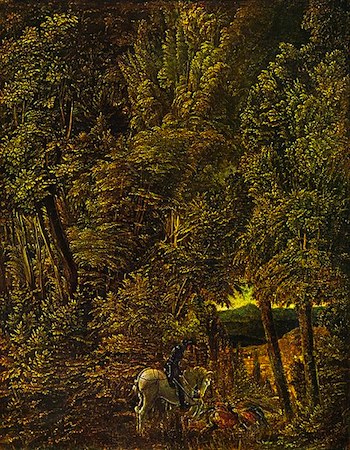

GM: I think I see multiple sides to Romanticism. It’s such a complex movement. What I was thinking of was not so much the warm, romantic with a small ‘r’ approach to nature but the approach that sees it as terrifying and overwhelming. For example, even going back into 16th century German art I think of Albrecht Altdorfer with his landscapes towering over very small figures, or of Bruegel’s Landscape With the Fall of Icarus with the human figures very small in the distance, on through Caspar David-Friedrich’s work [in the early 19th century] where you have the two extremes – you either have humanity dwarfed by nature, as in The Monk on the Seashore or you have humanity standing titanic over nature, as in The Wanderer over the Sea of Clouds. So it was in that sense I was asking about nature. Your quote was very striking [in Burden of Dreams] where you mention the jungle as being “full of obscenity … nature here is vile and base.”

WH: Yeah. Obscenity – that was because Kinski kept saying everything is erotic. And he would hug a tree and fornicate with it. [Laughs] Which is really against my inner convictions.

GM: But this comment about the ‘harmony of overwhelming and collective murder’ – setting aside Kinski’s comments, is that how you would see that particular jungle, or nature in general?

WH: No, you would have to be a little bit cautious. It’s a rant ‘against’ the jungle, but it came at a time of enormous strain on me – weeks and weeks and weeks where there was every single day a major disaster. And when I speak of major disaster I mean disasters like two plane crashes. Two consecutive plane crashes, and on and on and on. So, yes you have to see it in the context. But otherwise, thinking about the jungle, it’s not completely wrong what I said. But the ferocity of the rant is in a way a result of enormous pressure of disasters one after the other. … And it’s OK, I still like my rant.

GM: It’s achieved a cult status on-line. People enjoy it a great deal.

WH: But let me go back to when you speak of Altdorfer [see image below of Altdorfer’s St. George in the Forest] – or Matthias Grünewald. Yes, that’s where I feel much more affinity: late Middle Ages. But not Romanticism.

GM: And you have an interest in classical culture as well. I saw from your application for your Rogue Film School that you tell people to read Virgil.

WH: [laughs] I do not tell it – it is mandatory. But it’s actually Virgil’s – not the Aeneid.

GM: But I love the Aeneid!

WH: Yes, so do I, but it’s more the programmatic, big writing about celebrating the Roman Empire, celebrating the Augustean Empire, celebrating the evolution of the Roman republic into an empire. … [It’s]the Georgics – it’s about agriculture … about farming. And the beautiful thing is it does not explain anything – it just names the glory. It names the glory of pruning the apple trees, and it names the glory of the bee hive, and it names the terror of the pestilence invading the stables and killing off all the sheeps and goats. So I make it mandatory.

You’ve got to be serious if you want to apply to my film school. And applications, by the way, are open right now. I do it infrequently and at various locations whenever I have time for it. Basically Rogue Film School is an answer to an ever-increasing avalanche of young people who want to learn from me or work with me. I try to give a more systematic answer to it. There’s a mandatory reading list among other obstacles you have to overcome. You have to send in a written application, you have to send in a short film – and I read and watch every single piece.

And I’m the only one who ultimately makes the choice whom I invite. So it’s serious stuff. And of course it’s not just Roman antiquity included in the reading list. It includes the Warren Commission Report on Kennedy’s assassination, which is a wonderful piece of reading. It’s the ultimate crime story. Phenomenal in its conclusiveness and in its intelligence and I keep saying everybody puts it down without having read it. Just read it and you can’t get it any better.

GM: The Warren Commission Report, plus the Georgics – plus your reading list also includes Rabelais’ Gargantua and Pantagruel and Bernal Diaz’s The Conquest of New Spain. What effect do you think this variety of reading has on the filmmakers in your school?

WH: Well, I point one thing out: Read, read, read, read, read, read, read, read, read, read, read read. If you don’t read you will never be a filmmaker – a good filmmaker. So, these five or six books could be replaced by five thousand others. I might include a new book I just read that is [an] absolutely beautiful, wonderful piece. It’s called The Peregrine, by an English completely unknown person, J.A. Baker, who watches peregrine falcons. It was published in 1967 and there seems to be a new discovery going on of this book. It is phenomenally beautiful in its prose and in the precision of observation and this kind of – this unbelievable quest to meet the peregrine and an ecstasy of observation … Sometimes the writer lapses into “we”: “the peregrine saw us and swoops down and then we swooped down” so it is as if he were morphed into falcon.

GM: Somewhat like Timothy Treadwell [in Grizzly Man] wanting to morph into the grizzly bear.

WH: Yes, but the book has a phenomenal precision and quest and beauty. Can’t compare with Treadwell, that was just a misunderstanding, bears as being fluffy pets.

GM: An over-identification with them. Well you make the good point that there are limits between humans and nature, and the Native American man [in Grizzly Man] makes the same point about having a sense of limits.

WH: Yes, I think there was a massive misunderstanding of what constitutes wild nature. It’s a very tragic misunderstanding because it cost two human beings their lives and and at the end it cost two bears their lives who had to be killed by rangers. … The native Aleut people, for example, say very clearly you shouldn’t love the bear, but rather you should respect the bear. I think this is a very fine difference. …

GM: You’ve said you have an opposition to New Age culture … You’re opposed to yoga, nutritional supplements, self-help [Herzog laughs] and I found a quote of yours [in Planet Magazine] about Avatar – that you considered Avatar “an abomination because of its New Age schlock and bullshit,” despite its other accomplishments in terms of technique.

WH: Yes, we should not forget the accomplishments, but it makes me cringe, the New Age sort of content makes me cringe.

GM: So is it the element of pantheism, or that it’s this degraded Romanticism?

WH: Well, it has lots of things in it abominable, like degraded Romanticism, also, what did you say?

GM: Pantheism.

WH: Pantheism, yes, yes, yes.

GM: Inspired by Spinoza.

WH: Yeah, making nature as the ultimate God. Whatever. It combines all the stupidities of our time, not only these two stupidities, but it’s somehow the embodiment of stupidity and I just can’t take it without ranting. [laughs]

GM: So you have greater hope for humanity on its own – or for humanity and civilization perhaps? Or for rational progress? Do you believe in rational progress?

WH: Well, we should be cautious about that. Because the ice of rationality and civilization is kind of thin, this thin ice breaks easily and beneath there is an ocean of barbarism. And you can see it with Germany – a very civilized country with great poetry, philosophy, music and all this and within a very few years it lapses into a state of utter barbarism, and I mean an amount of barbarism we have not seen in millennia.

GM: How do you prevent that in the future from coming back? How do you foster a humanistic culture?

WH: Well, how do we prevent it? I do not know. It has really engaged my thinking. It’s a very, very important question. I even traveled to Africa when I was eighteen. I wanted to go … to the Congo, right after its independence because it was a breakdown of civilization and absence of everything that would be order – tribalism, and killings, [it was] staggering – and I tried to understand what was going on with Germany [by seeing] this, but I actually never made it to the Congo, I became very ill in the Sudan and I barely made it back alive.

GM: Do you think Weimar cinema of the ’20s predicted some of the Nazi barbarism? Or was it perhaps more just a symptom of it?

WH: [Exclaims] Maybe, yes, in retrospect, now we can say there was some sort of a vision of something dark coming. Nosferatu [photo above] is the best example, or Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is a good example. But they do not really explain – they had this mood of something impending – very dark coming at us. So cinema sometimes has a way to figure out the mood of something coming at us. So this is why I’m taking a good look at what is going on in mainstream cinema, and taking a good look at what television does, with Wrestlemania, and the Anna Nicole Smith Show, because the poet must not avert his eyes.

GM: It all reveals something – all the details. I look at the cinema and I believe it unconsciously reveals things that may be coming in politics or culture or society. There are very fascinating themes … I even see Weimar themes returning in some of the cinema today.

WH: Yes, but it’s not necessarily a direct parallel to ahead of time what’s coming – that would be dangerous. But sometimes these moments in cinema occur where you have the feeling , yes, yes, there is a premonition in the films.

Posted on December 2nd, 2011 at 10:57am.

What a great interview. Herzog is the filmmaker I’ve been searching for. He’s touched and explains the things that I’ve felt in my subconcious regarding our current culture and society. I’d love to read more conversations with him.

johngaltjkt – thank you! If you haven’t yet seen his films, you are in for a treat. They are different from anything else you will have seen, and are consistently surprising and inspiring. You can go from the darkness and madness portrayed in “Aguirre,” “Woyzeck,” and “Nosferatu” to the humanism of “Fitzcarraldo” (these last four films made with his great collaborator Klaus Kinski) to the whimsy and delight of “Encounters at the End of the World,” “The White Diamond” and “Cave of Forgotten Dreams.”

If you’d like to read more conversations with him, I really recommend watching a few of his films and then getting “Herzog on Herzog,” a book-length series of interviews with him that is a really lively and informative account of his whole life and career. In particular I think you’ll love the disdain he heaps on the Marxist radicals of the late ’60s who tried to rope him into the movement (he resisted, and they retaliated by excoriating all his films and calling him a reactionary), and his many colorful stories of working with strong-willed personalities like Kinski on his films. Here’s the Amazon link for ‘Herzog on Herzog”:

http://www.amazon.com/Herzog-Paul-Cronin/dp/0571207081/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1322939535&sr=8-1

Great interview, Govindini. Always a treat to hear Herzog’s ruminations.

I do, however, think he has some affinity with Romanticism (as Holderlin and Kleist did – I’d call them post-Romantics). I understand why he wants to deny it categorically – it’s easy to misconstrue an admission of Romantic tendencies. And he’s not wrong to note his Late Medieval sensibilities (especially if we call Cervantes “Late Medieval”).

Fun fact: I loved “My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done?’ Loved it.

“Razzle ’em, dazzle ’em…”

Thank you SeeSaw! I think everyone loves reading Herzog’s interviews because he is such a lively, well-read, and independent-minded person. I agree with you that Herzog’s films have a Romantic vision, however much he might deny it. I really see a strong continuity from the Germanic/North European visions of the late Middle Ages (Durer, Altdorfer, Grunewald, Bosch, Bruegel) to the Romantic artists of the late 18th/early 19th centuries. Interesting about Holderlin and Kleist being post-Romantics – I think there’s something to that. I’m a fan of Kleist myself, as well as of Buchner.

And I definitely agree with you on the Cervantes – Herzog’s films really have that picaresque, blackly comic yet humanistic sensibility. In fact I really wanted to ask him if he felt any affinity to the Spanish Golden Age picaresque novels (“Lazarillo de Tormes,” “El Buscon,”) but I didn’t have the time. Still, I was happy we were able to cover as many topics as we did!

Just to add one more thing. One of the reasons I loved “My Son, My Son” was because it finally made something click on a unifying theme in Herzog’s vast body of work.

When Michael Shannon is down in Machu Pichu he has a monologue (interior, if I remember correctly), where he goes off about how he doesn’t want to listen to his inner voice. Later in the film, he does listen to it, and he goes crazy.

Click! This is one way of stating Herzog’s consistent anti-New Age, anti-simplistic, anti-platitude maxim:

“Don’t listen to the inner voice.”

That’s a provocative and unqualified way of putting it, but what I see is a consistent warning from Herzog that our “inner voices” are as likely to be barking mad as brilliant and luminous. Same goes for nature, which – and this is the quasi-Romanticism of his work – serves as a kind of externalized metaphor for the inner voice’s danger and chaos. Nature, like our own exterior presentations, is prettied up and beautified; but at heart, it’s “inner voice” is much darker.

I have myself thought, on occasion, that Herzog somewhat overdoes it, but when you compare his relatively isolated position to the laughably overblown rosy illusions of the greater film world, his emphasis on the darkness and madness of the inner voice is perfectly understandable and legitimate. He’s saying something that demands to be heard.

Avatar made a lot of money, after all.

Great interview, Govindini. I have to admit that Herzog’s work has slipped under my radar too much, but I’m going to examine it closely.

His curiosity about man’s relationship with nature is pointed in the right direction, but I think he’s missing a little perspective.

Making nature god is more than the “stupidity” of our time, it’s the stupidity of pre-Christian history. Ancient Greece, for instance, shuddered in the fear of nature’s forces, so it would offer sacrificial blood or ritual orgies to placate them.

Then, thank the heavens — even if your a Christian or not — god spoke to Abraham, and unleashed the greatest force for individual freedom imaginable.

I will always remember what Chesterton said (I’m paraphrasing): Christianity drove out those gods, and made it possible for people to revel in nature with a free conscience.

It would be fascinating to examine how the forces of the state have attacked this ideology for thousands of years. It’s fascinating that men are so power-hungry that it’s been a common narrative throughout the ages — all the way to the people in Washington now.

“Avatar” had trappings of new-age nonsense, but there was a sense of a creator in it. The Na’Vi hunted, played, and generally held dominion over nature.

MOST importantly … Herzog gets on my bad side by equating professional wrestling to the Anna Nicole Smith Show. Pro wrestling is an extremely guilty pleasure of mine, and I get hairy when people dismiss it as anything less than theater. There’s lighting, stages, makeup, precise physical performances, and intricate storylines. It’s the action films of performance art, but art nonetheless. Stories get advanced in the ring through action, and when you get two people that can tell a story physically, it reaches hypnotic levels.

Sorry for the last rant.

Vince – thanks for your comment, as always. We will clearly have to differ on “Avatar” – I disagree that the Na’avi are shown as having dominion over nature – Cameron clearly depicts them as being one with nature and he has backed this up in numerous interviews. Also, I really cannot comment on pro wrestling having never watched any of it.

As for Herzog, he is a brilliant writer and filmmaker and I would really not say he’s missing perspective given one comment about the stupidity of worshipping nature. Also, Herzog does reference Christianity when he says he has a greater affinity with the artists of the late Middle Ages – all of whom created art within a strongly Christian viewpoint. Herzog is not a dogmatically or even overtly Christian filmmaker, but I think his comment about the late Middle Ages is very telling and worth taking account of. However, I should add that as a non-Christian myself I really do not think that Christianity has the ultimate answer when it comes to the relationship between humanity and nature. That is not to say I do not respect Christianity and frequently defend it in public – I do – but I also think there are other valid religious and mythological traditions out there. But that’s a subject for a much larger discussion.

In any case, I suggest you watch some of his films and read some more of what he has to say (in particular in the superb book-length interview “Herzog on Herzog”). I think you will find that Herzog is one of the most brilliant and original filmmakers out there when it comes to exploring humanity and nature. And while I am sure you will not agree in every regard, in many ways his work is quite in tune with your own perspective.

Govindini,

I realized after I wrote the response that I was a little hard on Herzon. I meant to work in my praise of his contributions, but I just hurried through it. His comments on the late Middle Ages in particular opened my eyes because that perspective is so rare, and really is a microcosm of his ability to be intellectually honest.

I actually own a couple Herzog films on DVD, but I put everything Netflix has in my queue, and I’m very excited about exploring them. Clearly his voice is unique and indispensable.

You also deserve a lot of credit for defending Christianity as much as you do. I frequently cite you and your work in discussions as an example of an intellectually honest person who isn’t a Christian.

It wasn’t my intention to say the Judeo-Christian belief structure has all of the answers, but the impact that the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob had on the role of the individual against the state can not be argued — that was my point.

Thank you very much for taking the time to respond to my comments. I really think this site does more to advance the cause of freedom than any other that simple engages the in Red vs. Blue game.

Herzog is one of my favorite artists ever since watching “Aguirre: The Wrath of God” – An excellent metaphor for The Third Reich – especially as he has the courage in this Leftist dominated movie making world to denounce New Age pagan crap like Avatar. A movie that may well end up an overture to another collectivist nightmare complete with tyranny, nature worship, concentration camps and killing fields, as there are many ominous parallels between the Weimar Republic of Germany in the early 1930s and the current situation in America.

Indeed, while our Western Civilization is a mile wide, it is only glass an inch deep that can easily be broken by modern day barbarians like Hitler’s SA Storm Troopers, or today’s Obama inspired OWS thugs. These are the barbarian armies of the night who are the criminal vanguard of a collectivist minority ruling elite of the Left in control of both major political parties at war with reason, progress and the American Republic. In 1933 the German answer to the anarchy of the Weimar Republic and the Great Depression was dictatorship of the “Right” Leftist Nazi Party and Adolf Hitler.

We all should be very afraid in America.

Yes, it can happen here.

But maybe it won’t….There exists the small band of heroes/artists/intellectuals like Herzog, Ayn Rand and Govindini willing to tell the truth and stand up for reason and the American Republic, when all about them the culture worships the dark evil gods of the New Dark Ages.

Cheers, Ronbo