By Jason Apuzzo. By some cosmic irony, yesterday was the day I’d finally worked up the fortitude to write about Jane Russell – the warm, glamorous and iconic 50s star whom Govindini and I had the pleasure of spending time with several years ago, before she passed away recently at her home in Santa Maria. I wanted to share with Libertas readers some of the things she’d told us about her life and career, although I would be doing so with a heavy heart as she is now no longer with us.

Then came news yesterday that Elizabeth Taylor had passed away.

This is very sad news, indeed. Although Taylor had been in failing health for some time, and word of her passing was not altogether surprising, I must confess to still being stunned by the news. Elizabeth Taylor had overcome so many crises and health scares in her life that she seemed utterly indomitable – and I had assumed that her recent health scare would, like so many others, pass away into legend as another one of her epic brushes with misfortune. Alas, her many health problems have apparently taken their toll over the years, and so mortality has now folded even over Elizabeth Taylor, the great survivor.

Elizabeth Taylor and Jane Russell both deserve their own posts and remembrances, frankly. Both of them loom large as entertainment personalities of the 20th century, and as people for whom – for different reasons – I’ve developed an affection over the years. At the same time, many of the the things I’d intended to say about Jane can also and should also be said about Liz – and more generally about the women of their generation. We’re all missing these women terribly right now, and missing what they represented. Everything I’m seeing written about Liz at the moment resembles what was said about Jane just a few weeks ago: that women of their sort are no longer with us, and that the women who’ve replaced them in the intervening decades since their heyday haven’t made up for the loss. Fundamentally, we all know this to be true but are so often restricted for various reasons from saying it.

Now is not the time for such restrictions, however. Now is the time to be emotional and passionate about the women on our big screen. So I have a few thoughts today about Elizabeth Taylor – arguably the greatest female star of all time – and also about Jane Russell, the girl-next-door who became an icon of her era. And you’ll forgive me, but I will be wearing my heart way out on my sleeve. These women deserve that.

—

First, let’s talk about Elizabeth Taylor. A movie star, I’ve always believed, is a person about whom two things can be said: first, that they’re somehow ‘larger than life’ – lovelier, more heroic, more honest, wiser than you are – and secondly that they somehow allow you to channel your own emotions through them. And it’s by these criteria that I strongly suspect Elizabeth Taylor was the greatest female star of them all. She was, on the one hand, an extraordinary beauty – no less than William F. Buckley, Jr. once crooned to Govindini and I about Liz’s “radiant skin,” although I strongly suspect Liz’s greatest assets were actually her penetrating eyes. She was also voluptuous in the 50s way, and generally ravishing without having to work hard at it.

The crucial factor with Liz, however, was the way that women in particular were able to identify with her. One of the things that is most astonishing about Elizabeth Taylor is the breadth and depth of her following among women of every age. Women of my parents’ generation identify deeply with her because Liz suffered in big, public ways – and triumphed in equally big, public ways – and never failed to bring her sufferings and triumphs into her acting. She was, as we so often say nowadays, real. She shared of her joys and sufferings, and infused her craft with the highly strung emotions that were apparently the substance of her daily life.

And she had strength.

Take some time in coming days to watch Liz’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof from 1958. The film, written by the great Tennessee Williams, concerns a woman (‘Maggie the Cat’) who gives all of herself in an effort to resuscitate her brooding husband (‘Brick,’ as played by Paul Newman) – a drunkard who has essentially given up on life. Maggie’s entire mission in the film is to breathe life back into a husband wracked with guilt over the death of a friend, and harboring a volcanic resentment toward his father. She does everything she can – intervening with the family on his behalf, throwing herself at him sexually, bombarding him with guilt. She abases herself in ways that make you cringe, because of Liz’s astonishing beauty and natural elegance. You want to slap Newman, frankly, and tell him to get his act together.

What is astonishing about Liz’s tense, mercurial and sexy performance – easily one of the best of her career – is that it was filmed a mere three weeks after the death of her real-life husband, Mike Todd, in a tragic plane crash. (Liz herself was supposed to be on that plane with her husband, but had to back out at the last minute due to a virus.) I find Liz’s performance in the film under these circumstances almost unbelievable, and certainly suggestive of the ‘bravery’ about which women of a certain generation always speak of Elizabeth Taylor. It’s one thing to give a great acting performance under any circumstances; it’s quite another when the character’s tribulations amplify a fresh tragedy in one’s life. Liz dealt with pain head-on; that was her style, and the habit of her generation.

This is why in later years, as Liz accumulated more husbands – and a breathtaking collection of jewels – even women who might otherwise be prone to envy could only shrug. Liz earned every bauble she got with heartache and suffering – and a willingness to share those emotions with her audience.

I think that women of younger generations marvel at Liz for a different set of reasons. May I be blunt? Younger women don’t feel respected nowadays. They feel that they’re treated like garbage by febrile men, dopey cads who don’t deserve the sight of their ankles – let alone the many other delights women are willing to show them free of charge, nowadays. Younger women look at the way men courted Liz – the way, for example, the epically Rabelaisian Richard Burton nearly bankrupted himself (happily) buying her jewels – and ask themselves: why can’t a man do that for me? Young women also look at Liz’s career and ask themselves how she was able to demand such an extraordinarily rich range of roles – moving as she did from Tennessee Williams plays, to Shakespeare, to Cleopatra.

How did she do it? How did she inspire men to pay her such homage?

The answer, I humbly conjecture, was self-respect. Liz Taylor came into prominence during the 1940s – but the era she really owned (arguably more so than even Marilyn Monroe) was that of the 1950s. The 50s are often derided – typically by people who don’t know any better – as a backward era of domestic repression for women, a grim, paleolithic precursor to the more enlightened era of the Flower Children. Nothing, of course, could be further from the truth. The 1950s were years in which women flooded the American workplace and higher academia – a trend that has become permanent. These were also the years when Dr. Gregory Goodwin Pincus began the first large scale testing of The Pill – a medical innovation that would revolutionize women’s sexual freedom in perpetuity. The 50s were also the decade in which first rate women intellectuals like Simone de Beauvoir and Ayn Rand gained massive worldwide audiences with best-selling classics like The Second Sex and Atlas Shrugged; where are their like today?

Riding these tides of professional and sexual liberation, women of this era also had a tremendous sense of pride and self-respect – and it was during this era that Liz became the ultimate middle class heroine. Beginning with her first adult role in 1949’s Conspirator, in which she played the wife of a secretive communist agent (played by Robert Taylor), Taylor ran off a series of highly provocative domestic melodramas like A Place in the Sun, Raintree County, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and Suddenly, Last Summer in which Liz’s characters struggled to maintain their dignity and sanity against overwhelming odds. Most poignantly, these struggles were typically carried out against friends, lovers and family members. Before women’s liberation became a political cause in the 1960s – and as such, so often merely an arid spectacle of marches and sit-ins – Liz was fighting for women’s freedom in their personal lives, where freedom (for both women and men) is most deeply felt. Liz’s characters are routinely having their minds and hearts invaded, particularly by the people closest to her, but she maintains her sanity and poise throughout. It was the sense and spirit of that struggle that, I believe, defined Elizabeth Taylor as an actress and star to her middle class audience – especially among women. Her struggle for dignity and self-respect was theirs.

A perfect example of this was 1959’s Suddenly, Last Summer – again written by Tennessee Williams. In that film, Liz is thrown into a mental institution and threatened with a lobotomy, because she stands in the way of one couple’s avarice – and also because her memories are an inconvenience to her aunt (the daft and imperious Violet Venable, as played by Katherine Hepburn). Her own family accuses her of being a liar and wicked – even when they know deep down that she’s nothing of the kind. Liz refuses to buckle, however, and ultimately it’s the venal couple and her aunt who fold.

Suddenly, Last Summer features an extraordinary sequence near the end in which Liz delivers a lengthy, emotional, recollective monologue with the camera on her for what feels like 15 straight minutes. The sequence frequently shifts to split-screen, with Liz narrating a jarring tale of ritual murder as her family and her analyst (Montgomery Clift) listen to her in rapt attention. This sequence may be the best 15 minutes of acting I’ve ever seen. The range of emotions Taylor is required to summon for this scene ranges from heartache to exaltation, from despair to serenity – and everything in between. It’s probably her masterpiece.

Performances of this kind – and there were many such performances in her career – give the lie to the contemporary notion that what defines a ‘strong’ woman is her ability to karate chop men, or unload Kalashnikov clips, or conduct one’s sex life as if it was a plein air burlesque show. Liz Taylor’s strength on-screen consisted instead in her integrity, her resoluteness of spirit – even when subjected to psychological torture by lovers and family members. Audiences loved her for this strength, and saw it paralleled in her personal life.

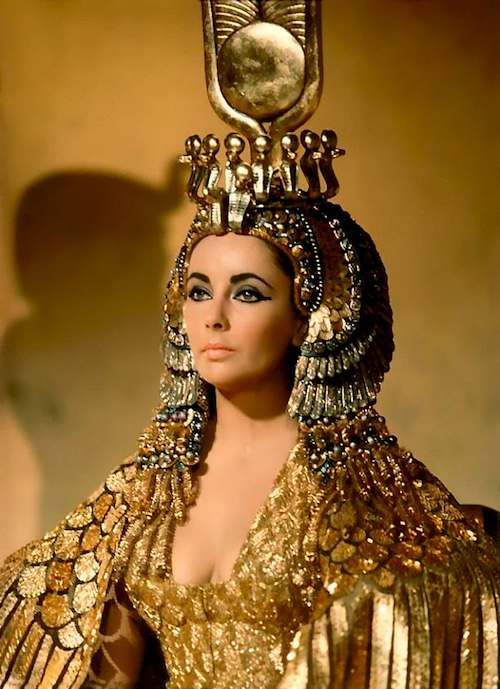

There’s so much more I’d like to say about Liz – perhaps I’ll say more down the line, or other Libertas writers will. I will state that my favorite film of hers is without a doubt Cleopatra – although I don’t think that was her best performance (probably that was Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?; by strange coincidence, Govindini and I just met Haskell Wexler on Monday, who won an Oscar for his cinematography on that film). Turner Classic Movies will be devoting all of April 10th to Liz’s films, so be sure to check that out. Some minor classics that are worth looking at, that aren’t on the April 10th bill: Elephant Walk, The Sandpiper and Reflections in a Golden Eye.

Cleopatra is a big, sumptuous, intelligent epic – it was also the kindling that lit the flame between Liz and Dick Burton, and lead to the Vatican accusing her of “erotic vagrancy” (best phrase ever). And, of course, it was the last time a studio was willing to risk everything on a woman’s film. Nowadays studios won’t risk anything on a woman’s film – and both women’s and men’s emotional lives are shallower as a result.

We’ll miss Liz and her inner strength, the poignant correlative to her outer beauty. She was the greatest on-screen heroine of her era, and young actresses today would do well to follow her example.

—

And now Jane Russell. Jane Russell! When speaking of Jane Russell, one shifts the frame of reference slightly. As much as Jane Russell was a down-to-earth gal, the ultimate girl-next-door, she really belongs most to the realm of fantasy – something the American cinema did particularly well during the 1950s.

Govindini and I invited Ms. Russell to a Liberty Film Festival event back in 2007, and she gracefully came along and gave a wonderful, charming speech. We got to know her better by spending an afternoon with her the next day at a friend’s house in Santa Barbara. More on that below.

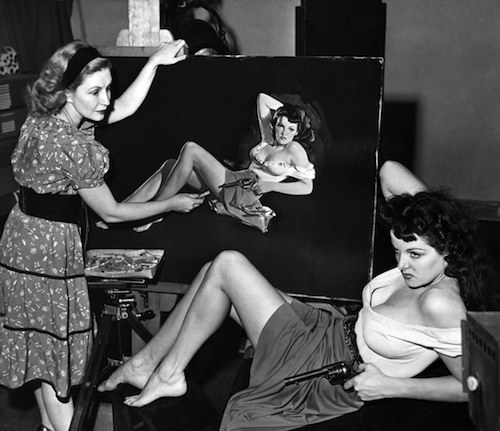

One of the things we learned that day was that Ms. Russell actually began her Hollywood career with rather serious acting ambitions. She’d been discovered by Howard Hawks – not, as many have claimed, by Howard Hughes – and began studying acting under the great Maria Ouspenskaya, formerly of the Moscow Art Theatre. Hawks was building The Outlaw around Jane at the time, hoping that she would become his latest ingenue-discovery. Yet Hawks would eventually clash with the film’s famously fickle producer, Howard Hughes. Being no one’s fool, Hawks eventually walked from the picture – leaving the film in Hughes’ hands.

This led to a complex situation, because Hughes took two years to complete the picture – although it would not actually receive a general release until five years after wrapping. During that time, Jane did endless rounds of publicity, and became famous as a World War II pinup – with hardly anyone having actually seen her film. The endless rounds of publicity Jane did focused, of course, on her spectacular figure – and Jane joined an elite sisterhood of pin-ups like Rita Hayworth and Betty Grable who became dream girls for the GIs. At the same time, this endless publicity – some of which she found lurid and demeaning – probably set up unrealistic expectations regarding the film, and her performance in it. Howard Hughes was never quite as bad a director as people have claimed (I love his Hell’s Angels, with Jean Harlow) – but he certainly was no Hawks, and The Outlaw ultimately did have a lukewarm reception.

We can only imagine what The Outlaw and Jane’s performance in it might’ve been under Hawks’ guidance. Nonetheless, the film launched Jane’s career – and, due to its sexy publicity campaign, made her a household name.

A word should be said here – many words, actually – about Jane’s sexiness, which was iconic in her time. There is a certain kind of fleshy, plush, primal sexuality that the women of 1950s films projected, a kind that was highly distinctive to the era – and shared, of course, by Elizabeth Taylor. This was the era not only of Jane Russell, but also of her friend Marilyn Monroe – and memorable bombshells like Mamie Van Doren and Jayne Mansfield. Was it simply that the women were often large-breasted? Not entirely. The 1950s were certainly an era of ‘superabundance’ in most respects, as Americans finally began to enjoy a taste of luxury – the good life – after suffering through the deprivations of the Depression and World War II. Americans were also in a mood during the Cold War era to celebrate their superabundance in contrast to the wretchedness of life behind the Iron Curtain. Yet it was more than that.

It was more that everything about these women was large – up to and including their personalities.

I say this because Jane was no shrinking violet. She was a strong, brassy, self-confident woman both on and off screen. Jane made a point of telling Govindini and I, for example, that she was proud to have formed her own production company with her husband (the great Rams quarterback Bob Waterfield) during the 1950s so that she could do precisely the kind of films she wanted. It was very important to Jane, particularly after her early-career experiences, that she be paid well and not taken advantage of. As I listened to her recount these things, I could only think of today’s starlets – who seem to give away so much of themselves, in return for nothing.

Jane’s career really started to take off when she made two classic noirs with her close friend, Robert Mitchum: His Kind of Woman (1951) and Macao (1952). If you haven’t seen those films, give them a try – they’re great fun. Jane told us that director Josef von Sternberg, late in his career and behaving like a martinet, lost control of the cast and crew during the filming of Macao – and deserved his firing by producer Howard Hughes. And although Nicholas Ray was brought in to finish the film, Jane basically credited Mitchum with finishing the film – as Mitchum apparently rallied the cast to improvise and come up with the dramatic business necessary to fill out the story. Jane also said that Mitchum always looked out for her, and was a loyal and devoted friend. They certainly made one of the cinema’s sexiest on-screen couples. Maybe the sexiest?

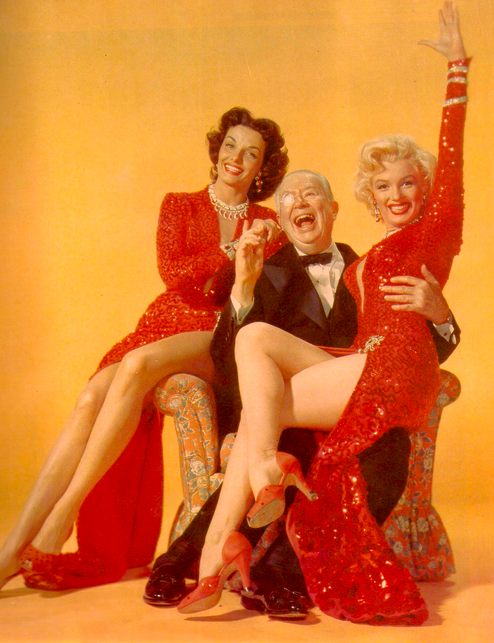

Jane finally got her chance to work with Howard Hawks, of course, in his 1953 masterpiece Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. I lack the vocabulary to describe what an utterly perfect film it is – it’s humor, sexiness, and cheeky lustre are unmatched in the history of the cinema. Jane Russell and Marilyn Monroe in the same film?! Are you kidding me?! The mind reels – it’s actually just beyond what the male imagination should try to handle, at the risk of inducing some kind of priapic madness. I have the film on my shelf these days, but I actually try to stay away from it. It’s just a little too good, if you know what I mean. In any case, this was certainly Jane’s best film and best performance – the movie in which she finally got the chance to show the full range of her talents, in terms of her singing, dancing, comic timing … and mind-shattering curves.

Jane told us some important things about that film: specifically, that Marilyn needed a lot of encouragement and propping-up behind the scenes. It was Jane who basically got Marilyn to the set each day by bucking her up, calling her “kiddo,” and filling Marilyn with a confidence she generally lacked. She was something of a big sister to Marilyn on that film, one of the few people Marilyn could trust. That chemistry really shows in the film. Gentlemen is, among other things, one of the best ‘buddy’ films ever made – largely because Jane and Marilyn really do seem to understand each other implicitly.

Jane’s next two films were made in 3D and are, in my opinion, something akin to undiscovered classics: The French Line (1954) and Underwater! (1955), both produced (again) by Howard Hughes. I’ve only even seen these films because Turner Classic Movies has shown them. The French Line is a musical comedy that sort of picks up where Gentlemen Prefer Blondes left off, with Jane playing an oil millionaires who heads to Paris to husband-hunt. (She finds Gilbert Roland.) Along the way Jane does some incredibly sexy musical numbers that – typical of the Hughes-Russell collaboration – got the film attacked by the Catholic Legion of Decency. If you’ve seen the film, it’s not hard to understand why – there’s certainly nothing ‘decent’ about it. The film features a kind of all-star cabaret of 50s bombshells, all photographed in three dimensions. Look closely at the cast and you’ll find a young Kim Novak, Joi Lansing, Jean Moorhead, Barbara Darrow, Gloria Pall, Shirley Patterson and Pat Sheehan … the list goes on and on. These women were legends, major sex goddesses in their day – although they mostly pale in comparison to Jane, especially during her boffo 3D musical numbers.

The French Line’s advertising slogan? “J.R. in 3D. It’ll knock both your eyes out!” No kidding.

Underwater!, as its title implies, was in some respects an excuse to get Jane in a bikini underwater – and photographed in 3D. That’s true so far as it goes – and what’s wrong with that, by the way? – but the film is also a highly entertaining sea adventure about hunting for sunken treasure in the Caribbean. Directed by the great John Sturges (The Magnificent Seven, The Great Escape) the film stars Jane, Gilbert Roland, Richard Egan and 50s cutie Lori Nelson. Jane told me an interesting behind-the-scenes detail about this film, one of those details that suggests how powerful women like her were in the 1950s – as opposed to today. Apparently when Jane decided to do the film, she insisted on casting whomever played her husband. To be blunt, she wanted a stud – because the public knew she was already married to one in real life (her husband, Rams quarterback Bob Waterfield, won the NFL MVP award as a rookie). So she insisted on the casting of macho Richard Egan – but she wasn’t crazy about his hair color, so she also insisted Egan die his hair color blonde. Egan agreed. Why the hell not? After all, he was going to be in the Caribbean clinching with Jane Russell.

Now, let’s stop here for a moment. In our more ‘liberated’ era of today, what female star could get away with that? Angelina Jolie, you say? I doubt it. Today’s pampered male stars would never put up with that sort of thing. Jolie actually lets herself get punched by a man at the end of Salt. You think Jane Russell would put up with that? Not a chance, friend.

After a series of middling films, Jane’s career went into a gradual decline in the late 1950s and 1960s, but Jane didn’t seem to have been shattered by that. She was already a legend at that point; plus, her faith in God was strong, she had many close friends – and her adopted children – and she’d never let her stardom get to her head, to begin with.

I can’t tell you how nice Jane was to us in person. She took time to make delicious iced tea for us, padding around the kitchen, chatting pleasantly about her former husband, “Bob.” (She had so many famous ‘Bobs’ in her life: Bob Waterfield, Bob Mitchum, Bob Hope.) When we were first introduced, she said “Call me Jane.” I tried, but I couldn’t do it. Instead I called her “Ms. Russell,” and during most of the time Govindini was speaking to her, I was videotaping the interview on bent knee – as Jane sat, resplendent, in a golden chair.

This seemed quite appropriate. Women like Jane Russell should only sit on golden chairs, and be approached by men on bent knee.

—

So today, I’m missing Elizabeth Taylor, and I’m missing Jane Russell – and the type of American woman they represented: strong, independent, self-respecting, earthy, demanding, confident. We need this sort of American woman today, badly, as much as we need strong men of the John Wayne-variety. The two are inter-related, actually. You know why our men on-screen today are so weak and pitiful? Part of the reason is because women demand nothing of them. Women of the Elizabeth Taylor-Jane Russell vintage expecting a lot from their men – and usually received it, in the form of worship and veneration. We don’t call them screen ‘goddesses’ for nothing.

Posted on March 24th, 2011 at 5:47pm.

I believe that I’ve not been as effected by the death of a real star like this since the death of Lucille Ball. Elizabeth Taylor had it all. The class, the talent, the looks. Her personal life was her personal life and did nothing to me as far as diminishing her stature in my eyes as a singular talent and someone truly special. Truly the last great Star.

I had been very much hoping that either you or Govindini would comment on the passing of Jane Russell and Elizabeth Taylor, two of my favorite actresses and an important part of my movie going life when I was a teen ager and in my twenties. This was a wonderful tribute to them both and well worth waiting for. You really hit this post out of the park, Jason. I thoroughly enjoyed reading it. It was always so fascinating to follow the details of Elizabeth Taylor’s turbulent but nevertheless endearing life through all the following decades. When her acting became less of a factor in her life, she took on new roles, that of a very successful businesswoman with her line of perfumes, and that of an equally successful humanitarian, with her efforts to raise money to fight AIDS (she raised several hundred million according to some reports.) I felt so sad seeing reports of her recent decline, particularly in light of the way in which she was plagued by pain and ill health through so much of her life. Despite these, she was enormously successful in all three of her major endeavours, acting, business, and philanthropy. She also appears to have been a very successful mother, someone to whom her children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren were very important; and a very great and loyal friend to those whom she cared about. It has been wonderful to hear the tributes being paid to her in the last couple of days. What a life well lived.

I certainly feel that the same could be said of Jane Russell. How fortunate you and Govindini were to have been able to spend time with her a few years ago. It was a delight to be able to read about your interview with her (expecially the part about the iced tea!) Not many of us have ever had the experience of being able to meet and talk with an icon of the screen for such a long time. Would love to read a longer account of the interview with Jane Russell on the Libertas Film Magazine one of these days.

Thank you so much for writing this wonderful account today and for the marvelous way you have helped us to understand the contributions to the world of film made by these two amazing actresses.

Wonderful post Jason. That was really touching to read. We will always miss Liz, and how incredible that you got to spend that time with Jane Russell. What legends!

“I think that women of younger generations marvel at Liz for a different set of reasons. May I be blunt? Younger women don’t feel respected nowadays. They feel that they’re treated like garbage by febrile men, dopey cads who don’t deserve the sight of their ankles – let alone the many other delights women are willing to show them free of charge, nowadays. Younger women look at the way men courted Liz – the way, for example, the epically Rabelaisian Richard Burton nearly bankrupted himself (happily) buying her jewels – and ask themselves: why can’t a man do that for me? Young women also look at Liz’s career and ask themselves how she was able to demand such an extraordinarily rich range of roles – moving as she did from Tennessee Williams plays, to Shakespeare, to Cleopatra.”

The complaining women need to look at themselves. I am a big believer in Spengler’s Universal Law of Gender Parity: “In every corner of the world and in every epoch of history, the men and women of every culture deserve each other.” These women friends want male suitors to “bankrupt themselves buying her jewels”. I bet these same women would complain about how say their now husband or mate cannot afford the nice McMansion because he blew his life savings and went into debt buying said jewelery. Unlike the great Richard Burton, most men do not have the option of making some movies for the big payday.

WONDERFULLY WRITTEN!!

– PAUL

Many thanks!

Great article, Jason.

I love how you constructed a moving tribute to these women, and still applied it to the mission here at Libertas.

Your assessment on how the ’50s are portrayed is especially poignant, especially since that is an insult to exceptional women like Taylor, Russell, and even Ayn Rand, which you mentioned. I think it’s also interesting that the ’20s and the ’80s are even being attacked the same way. Three conservative presidents ushered in those eras of prosperity, and it drives their opponents crazy.

As for Russell, I think it’s important to mention her journey to becoming a pro-life advocate. No matter where you stand on that issue, you have to appreciate how she arrived at her belief, and the depth of this woman.

I also have to say that this sentence is classic: “They feel that they’re treated like garbage by febrile men, dopey cads who don’t deserve the sight of their ankles – let alone the many other delights women are willing to show them free of charge, nowadays.”

Brilliant.

Many thanks, Vince, that’s very kind of you.

My favorite Jane Russell movie was also Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. I keep meaning to see the sequel Gentlemen Marry Brunettes, but I haven’t seen it out on DVD. I will have to check out The French Line, it sounds great.

It’s a sad month to lose two great ladies. We definitely do not see their like anymore.