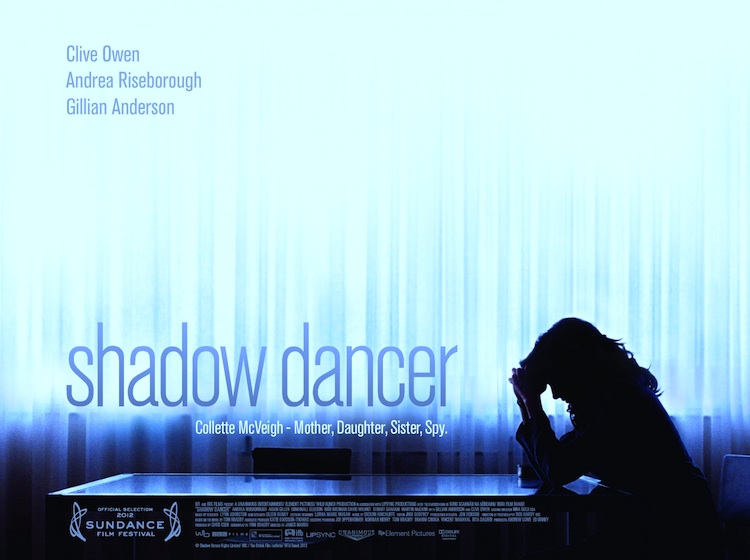

By Govindini Murty. The internecine conflict in Northern Ireland has provided potent cinematic subject matter for decades. Shadow Dancer, starring Clive Owen, Andrea Riseborough, and Gillian Anderson, is the latest film to dramatize this fraught topic. Directed by James Marsh (Man on a Wire) and currently screening at the Berlin Film Festival, Shadow Dancer tells the story of a young woman torn between loyalty to her radical IRA family and her efforts to protect her young son by becoming a spy for the British.

What is so striking about Shadow Dancer is that it portrays the British government in a positive light as it attempts to negotiate peace with the IRA – while portraying the radical IRA cadres who oppose the British as unregenerate fanatics.

When I recently saw the film at Sundance I asked director James Marsh and actress Andrea Riseborough if they intended the film to have a pro-British message. Marsh immediately assured me that the film was non-political and was intended purely as a drama examining the predicament of one particular IRA family. Riseborough differed from him, saying that she thought the film was sympathetic to the IRA.

This discrepancy suggests how hard it is to remain neutral in depicting political subject matter in the movies; one inevitably has to make choices about what to show or not show on-screen, and these choices in turn affect the perceived politics of a film.

As for the film’s meaning, it will be viewers ultimately who will be the ones to decide.

In Shadow Dancer, Andrea Riseborough (of Madonna’s W.E.) plays Colette McVeigh, a young single mother caught up in the terrorist activities of her staunchly IRA family in Belfast during the waning years of “the Troubles” in the early 1990s. Radicalized by the death of her little brother years before, Colette has been aiding her two IRA brothers, Gerry and Conor, in a series of bombings, shootings, and assassinations against the British and their loyalists. Unbeknownst to her family, Colette has been having second thoughts about the violence she is perpetuating – especially since she is now the mother of a small boy. When she half-heartedly drops off a bomb in a London subway without setting off the detonator, British intelligence picks her up.

British MI5 agent Mac (Clive Owen) persuades Colette it’s time to renounce her IRA terrorist ways and become a secret agent for the British. It’s either that or go to jail for twenty-five years and give up hope of raising her young son herself. Colette chooses to become a British agent, but her brothers’ continued terrorist activities, combined with the paranoia of a sadistic local IRA boss, place Colette in one moral quandary after another. Does she help the British and prevent further killings – but endanger the life of her family at the hands of the suspicious IRA? Or does she keep working for the IRA and take part in more assassinations, only to be arrested and locked away in jail by the British? A budding romance with Mac – her decent, well-intentioned MI5 handler – makes things even more complicated for Colette.

Director James Marsh takes an understated approach to the film’s direction and cinematography that effectively focuses attention on the characters’ moral dilemmas, rather than on external action or violence. The dialogue is sparse and the camera dwells on Colette’s silent face for long periods of time. The effect of this initially is to give Colette an enigmatic quality that adds to the suspense of the film, but ultimately the opacity of her emotions runs the danger of making her seem unsympathetic. Colette does some very unsavory things in the film, and I for one would have liked to have seen more emotion, more conflict on her face in order to be drawn into her predicament. Riseborough in person comes across as warm and emotional, so this strict, internalized approach was obviously part of Marsh’s minimalist aesthetic. When I asked Riseborough what she thought of her character’s emotional choices, she answered: “I was playing a young woman with a small child who was doing the best that she could.”

This minimalism also extends to the film’s settings, which range from the plain working class neighborhoods of Belfast to the grey tunnels of the London subways, to the banal, bureaucratic offices of British intelligence, to a cold, windswept pier lashed by rain. The film is shot in tones of blue and grey, with Colette’s bright red trenchcoat and a pivotal red phone booth providing the solitary jolts of color in the bleak surroundings.

The carefully-constructed nature of the film indicates that the political implications of what Marsh chose to depict on camera were also carefully considered. For example, the IRA are shown as carrying out the majority of the killings in the film, and even when the possibility of peace is held out to them, they are depicted as too radicalized to embrace it. Indeed, the IRA are portrayed as being even more ruthless toward their own IRA members and their families than the British. When Colette refuses to cooperate with the British, the worst that faces her is a twenty-five year jail sentence for her attempt to bomb the London subways. When Colette comes under the suspicion of the IRA, they’re ready to kill her at a moment’s notice, with no evidence or trial. They take Colette to a dingy safehouse where the sadistic local IRA boss Kevin interrogates her while an IRA executioner pulls out a gun and rolls out a sheet of plastic on the ground in case Colette gives the wrong answer. As one character says of the brutal, paranoid Kevin: “He won’t stop until he puts a bullet in someone’s head.”

By contrast Clive Owen’s Mac, the British MI5 agent, is shown as decent and dutiful. His goal is to end the violence in Northern Ireland and support the peace negotiations of the British government. When Mac and the MI5 agents pick up Colette after her failed subway bombing, Mac treats her with courtesy. He takes her to a hotel room that has been set up as a secret MI5 office and explains to her the reasons for helping the British. He doesn’t abuse her or intimidate her, and even offers her water. To underscore the urge to peace of the British, a TV news show playing in the background discusses British peace efforts with the IRA. Mac follows this by saying to Colette: “There is no future in violence.” Even the most equivocal character on the British side, Mac’s frosty boss, superbly played by Gillian Anderson (X-Files), is shown as acting out of a principled urge to protect her own long-time informants in order to support the larger peace negotiations.

It is against this backdrop of attempted reconciliation that the most radical factions of the IRA are shown as all the more intransigent. When the IRA leadership start negotiating with the British, Colette’s brothers and their IRA boss Kevin are furious, telling the IRA leaders that “they’ve never represented them.” Kevin proceeds to step up his program of bombings and assassinations, and casts an ever closer eye on Colette and her family, suspicious for any sign of ideological deviation. This is what ultimately happens to fanatical political movements: they devour themselves from inside, destroyed by intra-party fueding between “less pure” and “more pure” elements. Thomas Mann in his Reflections of a Non-Political Man called this the “fanaticism of purity,” and said it is what defines the radical nihilist. To the radical, ideological purity is more important than life, love, or humanity itself.

Political fanaticism is a fascinating subject, and the subject of Shadow Dancer is all the more timely today as we seek to find ways to encourage peace in the Middle East amongst rival, warring factions with lengthy historical grudges against each other. We in America still have a basically peaceful society that is informed by humanistic values and a respect for the individual (despite recent challenges) – but what does one do in those societies where the movement is more important than the individual, where ideology is more important than life?

Shadow Dancer is a timely study in political fanaticism. Whatever its filmmakers’ intentions, it delineates a clear-cut morality between those who believe in life, peace, and humanistic reconciliation – and those who believe in terrorism, ideology, and extremism no matter what the cost.

Posted on February 13th, 2012 at 11:31am.

2 thoughts on “LFM Reviews Shadow Dancer @ The Berlin/Sundance Film Festivals: A Timely Drama on the Dangers of Ideological Fanaticism”

Comments are closed.