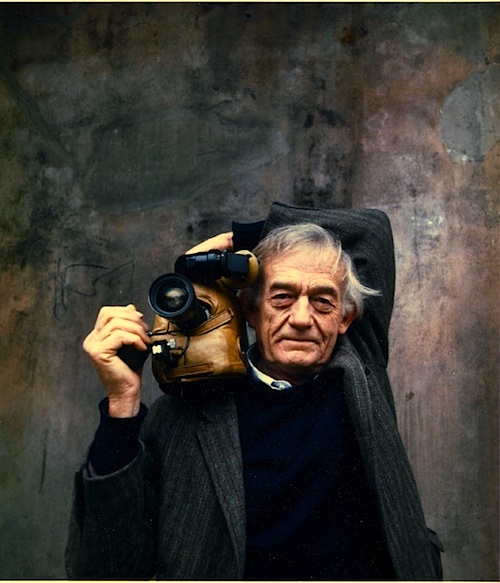

By Joe Bendel. For many, Richard Leacock was Mr. Documentary, directly inheriting the title from Robert Flaherty, with whom he once worked. Since his name is attached to many of the Twentieth Century’s acknowledged exemplars of the field, his reputation was not without merit. Longtime friend, colleague, and protégé Jane Weiner collects decades of footage she shot of the verité pioneer in her documentary profile Ricky on Leacock, which screens as part of the 2012 DocuWeeks showcase.

Leacock shot his first documentary as a teenager to serve as a PR film for his father’s banana plantation. Decades later, Canary Island Bananas is still regularly screened at Leacock tributes and retrospectives. Obviously not exactly from humble roots, Leacock was educated at private boarding schools. It was at one such institution Leacock happened to meet Flaherty, who promised to hire Leacock after viewing Bananas. Though Leacock dismissed the pledge at the time, he did indeed find himself side by side Flaherty shooting footage for Louisiana Story.

Frankly, Flaherty’s 1948 classic boasts some of the strongest images collected in Weiner’s documentary, along with the uber-cool visuals of Roger Tilton’s smoking short, Jazz Dance, on which Leacock served as a cinematographer with Jimmy McPartland’s combo providing the music (with Willie “the Lion” Smith on piano, Pee Wee Russell on clarinet, and the great slap bassist Pops Foster, oh yes indeed). Yet problematically, many of his grungy later super-eight micro-docs that fired Leacock’s passion are not so powerful looking when collected on-screen.

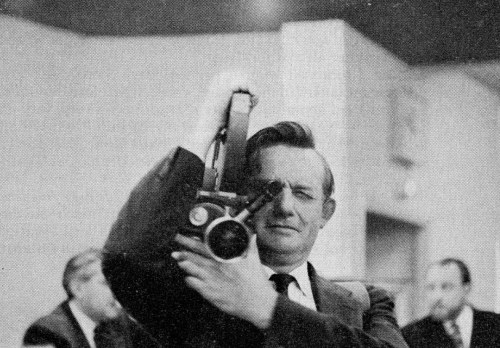

Granted, there are some interesting making-of stories about Leacock’s films, including his collaborations with D.A. Pennebaker, who shares some on-camera reminiscences. Yet, the fact is that Leacock’s oft repeated calls to “democratize” documentary filmmaking sound awfully dated in the digital age, as does the invective he directs towards television. His frustration might be understandable, but frankly if you cannot get anyone with a financial stake to share your vision for a project, perhaps that ought to tell you something – especially considering his filmography includes the sharply critical Ku Klux Klan—the Invisible Empire produced for CBS in 1965.

Regardless, Weiner cannot seem to get enough of her teacher’s words of wisdom. Granted, Leacock had a distinctive voice, but his opinions are not always as timeless as his best films. She also loves to watch him cook, which is fine the first few times we watch him putter about the kitchen.

The result is a moderately interesting oral history of documentary filmmaking probably best suited to the television Leacock so brusquely dismissed. Tilton’s Jazz Dance is highly recommended for all audiences (check out Jeff Van Gundy getting down around the 8:06 mark), whereas Ricky on Leacock is strictly for those who have an abiding fascination with the work of Leacock and select collaborators, like Pennebaker and Flaherty. It screens through Thursday (8/16) at the IFC Center in New York and then runs for a week (8/17-8/23) at the Laemmle Noho 7 in Los Angeles as part of the 2012 edition of DocuWeeks.

LFM GRADE: C

Posted on August 13th, 2012 at 1:37pm.