By Joe Bendel. Chinese film censors often seem to get rather acute cases of “approver’s remorse.” After allowing Lou Ye to screen his latest film at Cannes (to general acclaim) they suddenly demanded the director edit two “violent” scenes before allowing his film a Mainland theatrical release. Considering that several of Lou’s films have been banned outright in China and the filmmaker has openly defied a state imposed five year filmmaking prohibition in the past, this arguably represents progress. As with his previous work, the Party bureaucrats are protecting the public from an excellent film. New Yorkers can judge for themselves when Lou’s Mystery (trailer here), screens today at the 2013 New York Asian Film Festival.

Like most of contemporary China, the industrial city of Wuhan is sharply divided between the have’s and the have-not’s. In the opening scene, a reckless group of have’s runs over a woman. Their first response is neither compassion nor remorse. Hold that thought. Lou will return to the woman on the motorway in due time. However, he abruptly shifts his focus to Yongzhao, who is striving to become one of the have’s. As a result, he works late hours, leaving his wife Lu Jie to care for their endearing young daughter, An-an.

One day after school, Lu Jie is asked out on a playdate by Sang Qi. She is not particularly keen to get to know the woman, but An-an clearly gets on with the woman’s son like two peas in a pod. Reluctantly agreeing to subsequently meet the woman for lunch, Lu Jie is rather uncomfortable when Sang Qi asks for advice on how to handle her cheating husband. At that moment, Lu Jie observes her husband across the street, entering a hotel with a woman who is most definitely not herself.

Coincidences do play a role in Mystery, but many things happen for reasons not immediately apparent. Indeed, the police investigation of the opening incident will ultimately involve several of the film’s primary characters. These cases are called crimes of passion, correct?

Coincidences do play a role in Mystery, but many things happen for reasons not immediately apparent. Indeed, the police investigation of the opening incident will ultimately involve several of the film’s primary characters. These cases are called crimes of passion, correct?

In the past Lou has addressed topics like homosexuality and Tiananmen Square, which are absolutely radioactive as far as Party bureaucrats are concerned. Mystery implies much about contemporary China’s growing class inequities and the collapse of traditional values, but as an ostensive film noir, it is obviously much less controversial. Domestic critics have often unfairly rapped Lou for his supposed Euro-art house style, but in this case viewers can sort of see it. One might more readily compare his latest to Louis Malle’s Damage than Lou’s Digital Generation-esque Spring Fever.

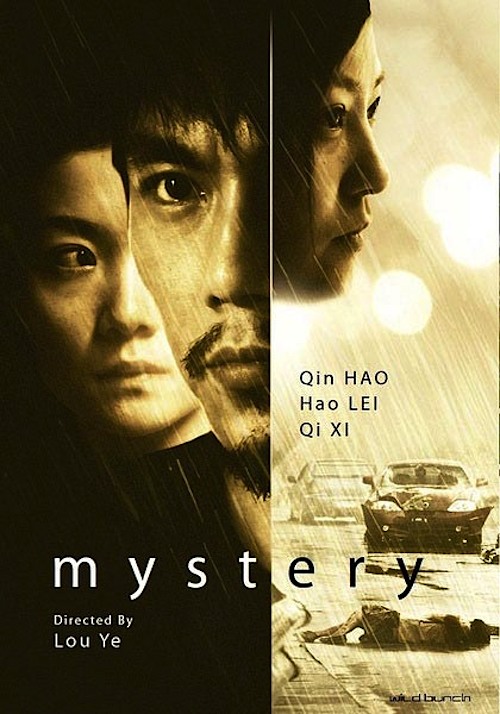

The star of Lou’s Summer Palace (a tragic love story bound up in the Tiananmen Square protests that went over with the censors like a lead balloon), Hao Lei is scary good as Lu Jie. She takes the audience on quite a ride with her character’s arc of development, vividly illustrating what “a woman scorned” means. Likewise, Qi Xi plays the seemingly naïve Sang Qi with surprising subtly and power. Keep your eyes on them both.

Without question, Mystery is a film for mature adults. While there are exponentially more violent films at this year’s fest, Lou presents the occasional outbreaks in disturbingly intimate terms. Taut and sophisticated, Mystery amply rewards viewers who indulgence its plot contrivances. An important new work from a truly independent filmmaker and an accomplished cast, Mystery is very highly recommended when it screens tonight (7/3) and next Thursday afternoon (7/11) at the Walter Reade Theater, as part of this year’s New York Asian Film Festival.

LFM GRADE: A

Posted on July 3rd, 2013 at 1:19pm.