By Joe Bendel. There is a Prime Directive applied to earthlings on this foreign world, but it is much less rigid than the version in Star Trek. Killing the locals is strictly prohibited, but a little gentle development guidance is encouraged. Unfortunately, the home-worlders have collectively turned their backs on intellectual enlightenment in the late Aleksey Yuryevich German’s science fiction-in-name-only magnum opus, Hard to be a God, which screens during the 2014 Seattle International Film Festival.

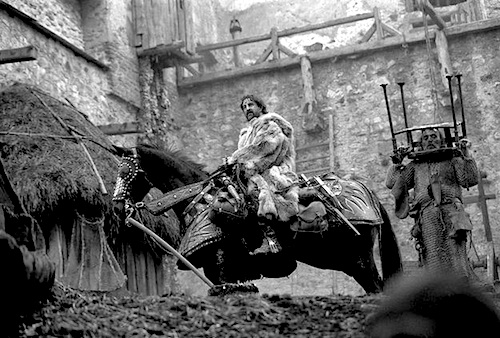

You should really fortify yourself for this one. Over a decade in the making, including some six years of principle shooting, German’s adaptation of the Strugatsky Brothers’ novel is not for the faint of heart or the short of attention span. Since Stalker was also based on a Strugatsky novel, Tarkovsky is often suggested as a comparison, but the dream-like vibe and highly composed black-and-white visuals are also somewhat akin to Guy Maddin at his most self-indulgent.

Let’s be clear: if you require a strong narrative through-line then stop right here. Throughout Hard German is far more interested in setting the scene and rubbing our noses in it than telling us what happens next. In the future, supposedly intelligent humanoid life is discovered on the planet Arkanar. Yet, just when its Renaissance period should have started, the state initiated a campaign against so-called “wise-guys.” Secretly integrating themselves into society as powerful noblemen, thirty scientists try to do what they can to protect the beleaguered intellectual class against the forces of the “Greys,” but Arkanar just does not want to be helped.

German focuses on Don Rumata, a rather rakish Earthling in disguise, as he ostensibly seeks out the hunted Dr. Budakh. However, he spends an awful lot of time farting around with his servants. From time to time, he will also do a solid for the Falstaffian Baron Pampa, while sparring with the Greys. Frankly, this probably makes Hard sound more plotty than it really is. Think large, festering set pieces rather than fights and chases.

Hard clocks in just under the three hour mark and German makes the audience feel the passing of each and every minute. He also supplies several years’ worth of the hardiest moviegoer’s cinematic quota for pee, poop, and snot. His vision (completed by his filmmaker son Aleksey Jr. and co-screenwriter wife Svetlana Karmalita) allows us no illusions regarding just what the Dark Ages entailed.

Nevertheless, cinematographers Vladimir Ilyin and Yuri Klimenko make it all look absolutely breathtaking, often in the manner of a Brueghel painting. (Ironically though, Lech Majewski’s The Mill and the Cross, an attempt to render a Brueghel canvas on film is somehow less static and more accessible than German’s world-building.) Yet, somehow lead actor Leonid Yarmolnik never wilts under the exhausting force of German’s mise-en-scéne. As Rumata, he is unflaggingly intense and roguishly charismatic, even when literally wallowing in the muck and mire.

This is an unusually redolent film. At times, you can practically smell the mud—at least we’ll call it mud for now. On the other hand, if you are waiting for a rocket ship or a ray gun then good luck to you. Although German passed away in early 2013, it is rather eerie watching Hard at a time when Putin also seems to be choosing militarism and barbarism. Indeed, the linkage between ignorance and state power is intentional and directly informed by the Soviet experience, but viewers still have to dig for it. Ultimately, Hard to be a God is a fascinating and often punishing film to experience. Recommended for those who want to be able to say they have seen it for themselves, it screens today (5/16), tomorrow (5/17) and the following Saturday (5/24) during this year’s SIFF.

Posted on May 16th, 2014 at 10:22pm.