By Joe Bendel. Amy Winehouse’s life was short but remarkably well documented. That would certainly help a filmmaker crafting a posthumous profile, but it was much less fortunate for her. Despite the somewhat dubious objections of her family, a sensitive yet cautionary portrait of gifted artist overwhelmed by fame emerges in Asif Kapadia’s Amy, which opens this Friday in New York.

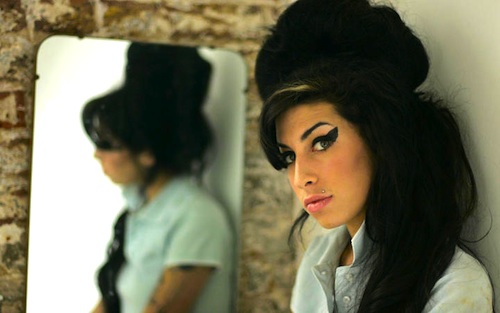

Amy Winehouse loved jazz and had the chops to sing it. If she had made a career of interpreting standards in moderate sized jazz clubs for a small but devoted following, she probably would have lived a much longer and happier life. Unfortunately, her talent was so conspicuous, she became a world famous pop star, but she was profoundly uncomfortable with much of the attention that followed. It is this Winehouse whom we see throughout the film, second by second, as her friends and associates speak over archival footage and still photos, including performances from the period before her tragic fame.

Much of the footage of the promising pre-celebrity Winehouse was supplied by her friend and original manager, Nick Shymansky. Despite original backing from the Winehouse family and estate, Kapadia’s film largely reflects the perspective of Shymansky and Winehouse’s lifelong friends, Juliette Ashby and Lauren Gilbert. Winehouse’s father Mitchel has made no secret of his objections, but through his position at the Winehouse estate, he can always tell his side of the story to a Guardian scribe whenever he wants. In contrast, the working class Ashby and Gilbert do not have the same access to media. Their only stake in this story was the loss of their dear friend. In fact, they had a deep distrust of the media, which Kapadia labored to overcome. Yet, that is precisely why their stories have such impact and credibility.

The general trajectory of Winehouse’s life is fairly well known: precocious talent gives rise to not-exactly overnight fame, which in turn leads to widely reported struggles with drugs and alcohol. By far, the most damning incident in the film involves Mitchel Winehouse undermining her friends’ early intervention, telling her she really had no need of rehab. While he has subsequently taken pains to argue that his opinion eventually changed on that score, Shymansky points out that this was a lost opportunity to get Winehouse treatment, before the entire world wanted a piece of her and the media hounded her every step. Mr. Winehouse can object all he likes, but the significance of the moment is inescapable.

As it happens, Mr. Winehouse is not the only member of her inner circle upset with their treatment in Kapadia’s film. Her second (and final) manager Raye Cosbert also takes issue with suggestions he was exploitative or at least insensitive to Amy Winehouse’s emotional turmoil. Whether that is fair or not, it seems clear from the film he could only relate to her as a pop act rather than the jazz artist she initially set out to be. Had he better understood her, he could have charted a career course that better appealed to her sensibilities.

Oddly, the sequence of Winehouse recording a duet of “Body and Soul” with Tony Bennett has received disproportionate press attention. Its inclusion in Amy certainly makes sense, but it is actually old news, having previously appeared in Unjoo Moon’s The Zen of Bennett (maybe some of our colleagues do not screen as extensively as they should). Regardless, the overall effect of Kapadia’s Amy is utterly devastating. It is a heartbreakingly intimate film that makes viewers feel like they are peering into her damaged psyche.

Although it might be controversial in some quarters, Kapadia deserves credit for portraying some figures in villainous terms rather than playing it safe. Editor Chris King also does extraordinary work combining the voluminous images into a powerful narrative. As a result, Kapadia’s Amy is a moving document of a gifted performer whose life was far sadder and briefer that it should have been. Highly recommended, Amy opens this Friday (7/3) in New York, at the Landmark Sunshine and the AMC Loews Lincoln Square.

LFM GRADE: A

Posted on June 30th, 2015 at 12:38pm.