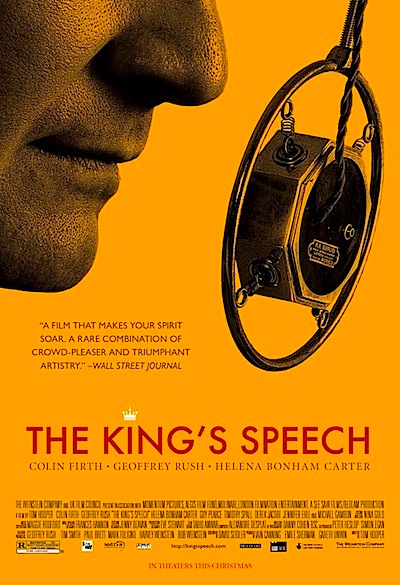

By Govindini Murty. The King’s Speech is that surprising thing – a film that glorifies the British monarchy while at the same time espousing American-style democratic principles. A warm-hearted, sumptuously-mounted film directed by Tom Hooper, The King’s Speech is the sort of feel-good drama that is likely to please Academy voters on Oscar night tonight and earn it a number of top prizes. In particular Colin Firth, who gives a fine, career-defining performance as King George VI, looks likely to take home the Best Actor honor.

By Govindini Murty. The King’s Speech is that surprising thing – a film that glorifies the British monarchy while at the same time espousing American-style democratic principles. A warm-hearted, sumptuously-mounted film directed by Tom Hooper, The King’s Speech is the sort of feel-good drama that is likely to please Academy voters on Oscar night tonight and earn it a number of top prizes. In particular Colin Firth, who gives a fine, career-defining performance as King George VI, looks likely to take home the Best Actor honor.

The King’s Speech tells the story of King George VI of Great Britain (the father of the current Queen Elizabeth II) and his struggles to overcome a speech impediment in the years leading up to his ascension as King. What gives this struggle its greater relevance is that George VI is part of a generation of royals in the 1920’s and ’30s who must learn to communicate in the new mass media of radio and film at the very time that dangerous totalitarian demagogues were using those mediums to threaten Western civilization. (The film highlights the double-edged implications of these new mass media when it describes, for example, the wireless radio as “a Pandora’s box.”) Oddly enough, it will be constitutional monarchs like George VI who, lacking any real political power, will instead function as the symbolic representatives of the people (an echo of the Hobbesian idea that the king is created by the covenant of the people), to articulate to them their nation’s support for freedom and democracy against tyrants like Stalin and Hitler who were working to wipe those freedoms out. As George VI says in the film as he readies to speak at the outbreak of war in 1939: “The nation believes that when I speak, I speak for them.”

The King’s Speech opens in 1925 with Prince Albert, the Duke of York (the future George VI), preparing to give a speech at the close of the British Empire Exhibition games. The Duke struggles tortuously through his speech, barely able to get even one sentence out. His wife Elizabeth, the Duchess of York (played with warmth and wit by one of my favorite actresses, Helena Bonham-Carter) looks on with pained love and dismay. As the story unfolds, Elizabeth brings speech doctors to Albert, but none of them work out and the Duke gives up the effort out of frustration. Compounding the problem, Albert’s father, the aging King George V (played by Michael Gambon), is dismissive of Albert’s struggle to speak and has repeatedly thrown him into public situations where he is forced to give speeches before large crowds. Albert’s older brother, Edward, the Prince of Wales (played by the nervy, angular Guy Pearce), is verbally articulate, but is a playboy who would rather romance married women than attend to his duties as the future king. Edward routinely mocks Albert’s speech impediment, only making his brother’s torment worse.

Out of desperation, Elizabeth goes to an unorthodox speech therapist, Lionel Logue, played with intelligence and impishness by Geoffrey Rush. Logue is a far cry from the genteel, expensive doctors the Duke and Duchess have been used to. His office is in a ramshackle old building in an unfashionable part of London, and he lacks even a doctor’s degree. However, Logue has the warmth and humanity – and the unorthodox teaching methods – to break through Albert’s icy shell of pride, pain, and frustration. Elizabeth persuades Albert to see Logue, and in a series of encounters – including their first one in which Logue democratically insists to Albert that they call each other by their first names, and that in his consulting room “we’re equals” – Logue works on Albert step by step to speak more clearly.

Logue may lack a serious medical pedigree (something that later leads to meddling officials trying to remove him from the King’s service), but he’s learned his skills as a speech therapist by helping shell-shocked World War I veterans – and he has the sensitivity to realize that the Duke’s problems are ultimately not physical, but emotional in nature, originating in the strictures placed on Albert early in his childhood by a cruel nurse and distant, uncomprehending parents. Thankfully, The King’s Speech is free of the usual cliched “training montage” that ends with a triumphal breakthrough for the protagonist. Rather, the Albert’s progress is shown to be slow and tortuous, requiring years of continual effort and few easy answers. This wouldn’t seem to matter so much, because Albert is after all the second son of the King, but his father King George V’s death in 1936 and his elder brother Edward’s sudden abdication as King in December of that year (in order to marry the American divorcee Wallis Simpson) suddenly thrusts Albert into the spotlight as the next monarch of Great Britain.

This is where The King’s Speech started to engage my interest in any serious manner. Truth be told, The King’s Speech is engaging and competent up to that point, but I’m used to well-made British period films – the British excel at them – and this one had somewhat dampened my enthusiasm early on by playing a number of scenes for easy laughs. As a potential Best Picture Oscar winner, I was hoping for more from the film than sit-com level jokes and a series of unnecessary scenes in which Albert is persuaded by Logue to swear with four letter words in order to “free himself” emotionally – scenes that historians have charged have no basis in fact and that are merely the latest example of our ’60s-inspired culture’s equation of the overthrow of civil norms with the acquisition of antinomian virtue.

However, as the clouds of war gather on the European continent and Albert prepares to become King George VI, the film draws into sharper focus the King’s need to speak clearly by contrasting it to the alarming rise of Hitler in Europe. This theme had been set up earlier in the film when the elder King George V lectured his son about the importance of speaking well over the new mass medium of radio because of the rise of Bolshevism in Russia and Fascism on the continent. As George V says to Albert: “Who’s going to stand between us, the jackboots, and the proletarian abyss?” If the King can’t articulate his role to the public, and serve the public by explaining to the world the need for their nation’s defense, he may soon find himself gone the way of his cousins the Russian czar and Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany – and worse yet, see his nation taken over by totalitarian tyranny.

There is one scene that communicates this idea especially well. Albert has just been crowned George VI in Westminster Abbey in May of 1937 and is watching the newsreels after the ceremony with his family. As the film switches to a newsreel of Hitler giving a speech in Germany, the projectionist moves to turn it off, but the king insists that it be kept on so he can watch it. He and the royal family watch in dismay as Hitler harangues a massive crowd in fluent, inflammatory rhetoric that is met with enthusiastic cheers. The newsreel ends, and the young Princess Elizabeth asks the king what Hitler was saying. The king replies: “I don’t know, but he seems to be saying it rather well.”

The implication is clear: Hitler, the evil tyrant who will soon plunge the world into war, is verbally adept and is able to use modern methods of mass communication – microphones to address huge rallies, radio and film reels to broadcast his words to the world – to persuade the German public to follow him down a nihilistic path of death and destruction. The only people who can challenge him will be the democratically-elected leaders of the world – and such symbolic figures as the royal families of Europe – who, although they hold no real power, must be able to speak persuasively to the public in order to remind them of their own humanistic traditions and inspire the public to defend freedom and life.

The King’s Speech dramatizes the need to take verbal adeptness seriously, to cultivate intelligent, well-spoken, principled leaders who can use modern means of communication to articulate crucial humanistic principles and fight back against the rise of totalitarianism and nihilism around the world. The end of the film states that thanks to his wartime speeches, George VI became to the British people “a symbol of national resistance.” In an era when American films feature heroes with supernatural powers who behave like kings and place themselves above the rest of humanity, how ironic that the Europeans – in this case the British – should make a film about a king who behaves like a human being and believes in liberty. Despite its occasional obvious moments, The King’s Speech is a fine, humanistic film that movingly supports the democratic principles that we here at Libertas hold dear.

[Editor’s Note: thus far The King’s Speech has won the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay (David Seidler).]

[UPDATE: Over the course of the evening, The King’s Speech won Oscars for Best Picture, Best Director (Tom Hooper), Best Actor (Colin Firth) and Best Original Screenplay (David Seidler)].

Posted on February 27th, 2011 at 6:37pm.

No one in America even watches movies, so this is all moot about a long dead and never-accepted media industry. Seriously, The Kings Speech is not a subject that even registers on Americas cereal boxes and why make a movie of Facebook when a prospective audience would rather just be on Facebook. A useless and senselessly ineffective waste of an industry and an award show most in America have never even heard of let alone seen and never will.

Really? Hollywood is a “never-accepted media industry”? And the Oscars are “an award show most in America have never even heard of let alone seen and never will”? Did you post this comment from somewhere near the outer rings of Saturn? [Also: if nobody watches these movies or cares, why are you bothering to comment on the matter?]

You might be interested to know that the combined worldwide box office take for The King’s Speech + The Social Network = around $445 million. That’s a lot of nobodies.

I wonder what got burr under MovieHeart’s sadle. To say that Hollywood is a “never-accepted media industry” is laughably wrong. Hollywood has ruled American media for decades, at least three quarters of a century, I’d say. Even now, though weakened by the new-media, Hollywood is still the media king. How much of the new-media is devoted to Hollywood gossip, I wonder?

I would be interested to know how much, and what kind of play “The King’s Speech” has gotten here in America. I don’t know the demographics, but I suspect that the movie is weak in the under 40, perhaps even under 50 demos–just the folks who should see the movie to get an idea of how dire things were at that time. “The Social Network,” on the other hand, probably did much better with the young.

When it comes to politicians I long ago stopped listening to what they say…I watch what they do. And MovieHeart it sounds like you need to get laid.

That’s a beautiful review, Govindini.

I wasn’t interested in seeing this film, but it seems, based on your review, that it weaves thematic elements very well. Maybe it’s just me, but it seems like so many writers are simply unable to craft anything other than potboilers, most of which depend on some sort of insane hook.

There’s just not many pictures that have simple narratives, but deal with complex themes. For that reason alone, I may go to the theater for this one.

AGREED!

Vince – thank you for your kind words. You make a very good point that too many movies depend on external plot trickery and contrivance, and not on organically developing complex issues of theme and character.

I always think of Bergman’s films and the films of the Italian Neorealists with respect to this. They told stories with only a few characters in simple settings, yet they captured a universe of emotion and complexity in their films that far outshines anything Hollywood can produce today.

I just watched a great parody of “The King’s Speech,” done on the Jimmy Kimmel Show. It was called, “The President’s Speech,” and the subject was George W. Bush. Interesting to me, as Bush…and the Roman Emperor Claudius was whom I was thinking about when I saw “The King’s Speech.” Both were considered less than intelligent due to their inability to speak well, yet both were far more accomplished as leaders than those that held power before and after them.

In the case of Claudius….Caligula and then Nero. One was more interested in sexual games than running an empire, while the other was more focused on himself while the empire crumbled. Clinton as Caligula might be a stretch, even with the Lewinsky scandal in mind…but Obama as Nero is looking more and more likely as America drowns in ever more debt and her power ebbing under his watch.

I thought Geoffrey Rush was brilliant as the King’s unorthodox speech therapist. I am, however, disappointed the movie was rated “R”, but it is such for a good reason: an uncomfortably funny scene laden with profanities during one of the King’s therapy sessions. Yet surely such a rich production by eminently talented people could have found a way to convey that frustrated cursing less graphically, and thereby be tagged with a PG-13 rating, in order to reach a much wider audience in need of this outstanding film’s greater message of “articulating the cause of freedom.”

Perhaps an intransigent Hollywood simply cannot help itself.

I agree completely. The profanity was completely unnecessary to what was otherwise a fine film. I did a little research and found it interesting that the cursing scenes actually had no basis in historical fact. As you point out, the scenes also harmed the cause of the film by restricting it to an “R” rating. From what I hear, a “cleaned up” version of the film with the profanity muted out will be released this year with a PG rating of some kind. It all seems so unnecessary, when they could have just not put it into the film in the first place.

John Galt, Anton, and everyone else – thank you for all your comments and the good points you raise as well.