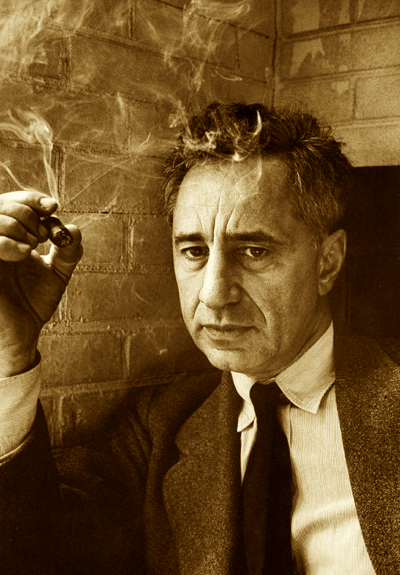

By Joe Bendel. No director portrayed the immigrant experience or the struggles of the common man with greater sensitivity than Elia Kazan – but to this day, he remains widely reviled on the left. Even a figure of Martin Scorsese’s stature took heat for presenting Kazan a lifetime achievement Oscar at the 71st Academy Awards. Yet for Scorsese, Kazan’s influence extended far beyond his early stylistic debt to the great filmmaker. Scorsese explains Kazan’s significance both to cinematic history in general and himself personally in Letter to Elia, an hour-long documentary he co-directed with Kent Jones, which screened with Kazan’s epic America, America at the 48th New York Film Festival.

Regardless of political controversies, Kazan’s reputation as an actor’s director is without peer. A co-founder of the Actor’s Studio, Kazan began his career on the boards before finding his calling as a theater director. Letter reminds us that it was Kazan who helmed the Broadway premieres of Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire and Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman. Of course, he would revisit Streetcar on film with original cast-member and frequent collaborator Marlon Brando, one of several legitimate masterpieces he crafted. However, for Scorsese, East of Eden stands out first and foremost in his consciousness, claiming to have “stalked” the film through second-run cinemas as a boy.

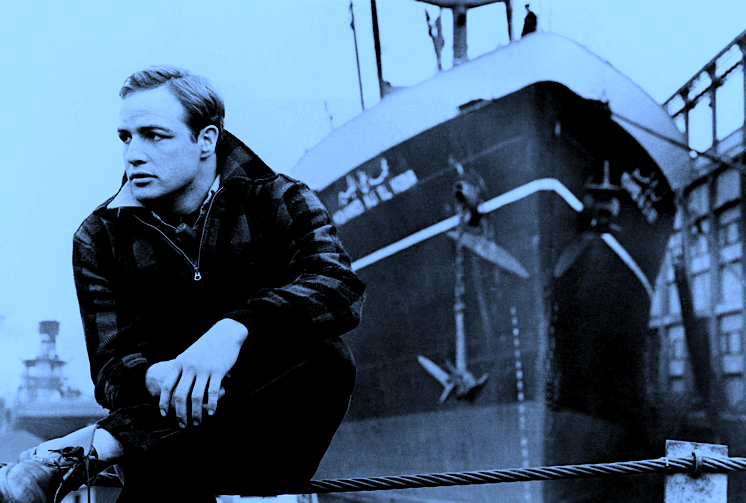

Looking straight into the camera, Scorsese forcefully and lucidly describes Kazan’s contributions to stage and screen, with the help of generous clips from the director’s filmography. While Eden and the best picture nominee America, America capture the most screen time, Scorsese and Jones duly include Kazan’s arguably single most famous scene, Brando’s “could have been a contender” speech from On the Waterfront, the classic tale of union corruption.

In contrast, they are clearly uncomfortable addressing Kazan’s testimony to the HUAC committee. Kazan was a former Communist who became disillusioned after the Stalin-Hitler (Molotov-Ribbentrop) non-aggression pact came to light. Considering Communism a severely flawed ideology, Kazan defended his decision in an op-ed piece, but Scorsese and Jones largely ignore his motivations, preferring to gloss over the incident with vague language of “difficult choices,” which does little to serve Kazan’s memory.

Of course, Scorsese is on solid ground when celebrating movie history. Letter is definitely an effective commercial for Kazan’s rich body of work, which really speaks for itself throughout the documentary. However, if any of his masterworks is under-represented, it would be Gentleman’s Agreement, a powerful examination of anti-Semitism that won Kazan his first Oscar.

Truly, Kazan is due for a critical renaissance, unblinkered by partisan score-settling. Letter is a well intentioned, mostly well executed effort to spur just that. Due to be included in a forthcoming Kazan boxset, Scorsese and Jones’ film screened yesterday (9/27) with a rare big screen presentation of America, America at the Walter Reade Theater, as part of the 2010 NYFF.

Posted on September 28th, 2010 at 9:04am.

Someone needs to remind these Hollywood people what was going on in the ’50s as these people “informed” on their former fellow Communists. Stalin had stolen the A bomb from us and had taken over half of Europe, millions of people were dying in gulags and had all their democratic freedoms taken away, and the US government was riddled with thousands of Communist spies. This fact is fully documented in the Venona files and in former Soviet archives.

Kazan was a hero for testifying and exposing the Stalinists who wanted to bring that tyrannical system to America. Someone ought to make a film about that.

On this subject, I would like to recommend to Libertas readers Richard Schickel’s excellent biography of Elia Kazan, which discusses in detail Kazan’s decision to testify before HUAC. The book is based on lengthy interviews Schickel did with Kazan and a lot of original research.

Schickel’s book reveals, for example, that Kazan was blacklisted himself from shooting a historical epic about modern Greece in the 1960s by Jules Dassin and his wife Melina Mercouri (a Greek actress with highly-placed connections to the Greek government), as payback for Kazan testifying before HUAC. What made this especially poignant is that Kazan himself is probably the most famous director of Greek descent ever, and his movie about the founding of Greece was a long-cherished project that he intended as a paean to his home country. Instead, the Communist-leaning Dassin and Mercouri completely blocked it. There’s your Communist “tolerance” for you.

Jason and I invited Schickel come and speak at a panel we held at the 2006 Liberty Film Festival on the subject of Communism in Hollywood and the blacklist. I had the chance to speak with Schickel about this issue when he spoke at the festival, and I found his attitude interesting. He told me that although he was an “an ADL liberal,” he felt that the Stalinists who were trying to infiltrate Hollywood and the US government were extremely bad people who needed to be stopped. That said, he didn’t like the behavior of HUAC either, but he was willing to condemn the Communists and their ideology.

You never get this from the Hollywood left today, and it’s a shame that Scorcese has to take the easy way out in his movie and not address the real evil that the Communists wanted to impose on America. In any case, I highly recommend Schickel’s Elia Kazan biography to everyone.