By Govindini Murty. The final film in the Harry Potter series is a pleasant surprise. Directed by David Yates, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part II offers a satisfying conclusion to the eight-film Harry Potter saga, finally allowing some light into the dark and providing a rousing depiction of the forces of good fighting back against the forces of evil. Deathly Hallows Part II moves along at a brisk pace, keeping things to a lean 2 hours and five minutes. The film provides a number of well-crafted action and suspense sequences, while not short-changing key emotional moments in which the characters reveal themselves in manners that are both dramatic and affecting.

This is all welcome because the prior installment, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part I, had been a rather melancholy affair. In Part I, the evil reign of the villainous Lord Voldemort had extended itself over all of England – with the forces of good apparently unable to fight back. Albus Dumbledore, the kindly and wise Headmaster of the Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry had been killed by the treacherous Professor Severus Snape. Teen wizard Harry Potter and his best friends Hermione Granger and Ron Weasley had dropped out of Hogwarts in order to hide from Voldermort’s forces while hunting down the “horcruxes” or splintered pieces of Voldemort’s soul that Voldemort had hidden away in order to evade death. Voldemort himself was on his way to possessing the “Deathly Hallows” – a set of three magical objects consisting of the all-powerful elder wand, the cloak of invisibility, and the stone of resurrection – that would make him immortal and invincible. The film’s bleak coloration, air of inescapable doom, and depiction of Voldemort as an all-powerful Hitlerian figure who installs a racist, Nazi-style regime that massacres non-magical human beings (known as “Muggles”), had made for rather depressing viewing.

Fortunately, in Part II things start to turn around as Harry Potter and his allies finally rally and fight back against Voldemort. A series of long-laid plans start to come to fruition, and we finally see revealed the full details of Harry Potter’s destiny. After a number of sequences that include a dramatic infiltration of a goblin bank, an escape on a white dragon, and the hunting and destruction of more horcruxes, the action culminates in the Battle of Hogwarts. A fantastic array of good witches and wizards, plucky Hogwarts faculty and students, animated stone statues, magical shields, swords, and spells are used to defend Hogwarts against Voldemort’s supernatural army of evil witches, wizards, ghouls, giant ogres, enchanted snakes, and shape-shifters. This could all make for rather busy and frenetic action, but director David Yates has managed to weave all these disparate characters and thematic strands into sequences that are coherent and compelling.

Fortunately, in Part II things start to turn around as Harry Potter and his allies finally rally and fight back against Voldemort. A series of long-laid plans start to come to fruition, and we finally see revealed the full details of Harry Potter’s destiny. After a number of sequences that include a dramatic infiltration of a goblin bank, an escape on a white dragon, and the hunting and destruction of more horcruxes, the action culminates in the Battle of Hogwarts. A fantastic array of good witches and wizards, plucky Hogwarts faculty and students, animated stone statues, magical shields, swords, and spells are used to defend Hogwarts against Voldemort’s supernatural army of evil witches, wizards, ghouls, giant ogres, enchanted snakes, and shape-shifters. This could all make for rather busy and frenetic action, but director David Yates has managed to weave all these disparate characters and thematic strands into sequences that are coherent and compelling.

In doing so, this last Harry Potter film illustrates what may be the key achievement of the entire series, which is to create a complex fantasy world that fuses mythological and cultural symbols from a number of traditions, while still maintaining a forward-moving momentum and narrative clarity.

My Libertas co-editor Jason Apuzzo commented recently on the information-dense, “palimpsestic” quality of Michael Bay’s Transformers films, and I have to say that that quality very much characterizes the Harry Potter films, as well. In fact, it may be the defining characteristic of the major fantasy/sci-fi film series of the modern era. This trend most notably began with George Lucas’ mythologically-rich Star Wars films, continued through the Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter films, and is now fanning out into innumerable other fantasy and sci-fi novels and movies.

As was famously the case in the Star Wars films (which similarly centered on a gifted orphan boy with a mysterious destiny linked to a dark lord), Lucas synthesized the mythological studies of Joseph Campbell, Japanese samurai culture, European medieval chivalric lore, Wagner’s Ring cycle of operas, and early twentieth-century sci-fi (such as the Flash Gordon movie serials) into a brilliantly imaginative whole that is still the sine qua non of the sci-fi adventure genre. In the latter trilogy of the series, Lucas even expanded his set of references to include the Byzantine, Indian, Tibetan, and Renaissance Italian cultural traditions.

The Harry Potter films are not quite as vast or cosmopolitan as the Star Wars films, as they mostly stay within the ambit of the English/European tradition, but they still contain such a wealth of mythological references that they have spawned an entire sub-genre of books dedicated to explaining the terms and lore of the series.

Perhaps this is the sort of story-telling that we get in the mature stages of a civilization: that characterized by dense, detailed plots, synthesis of many different cultures and traditions, baroque levels of complexity and contrast, webs of references to other films, artworks, and works of literature. These movies are like intricate tapestries, or vast mosaics made up of millions of tesserae, such as those found in late imperial Roman villas. They are virtual repositories of the past, cinematic museums that preserve our cultural traditions, while presenting them to us in a transfigured form.

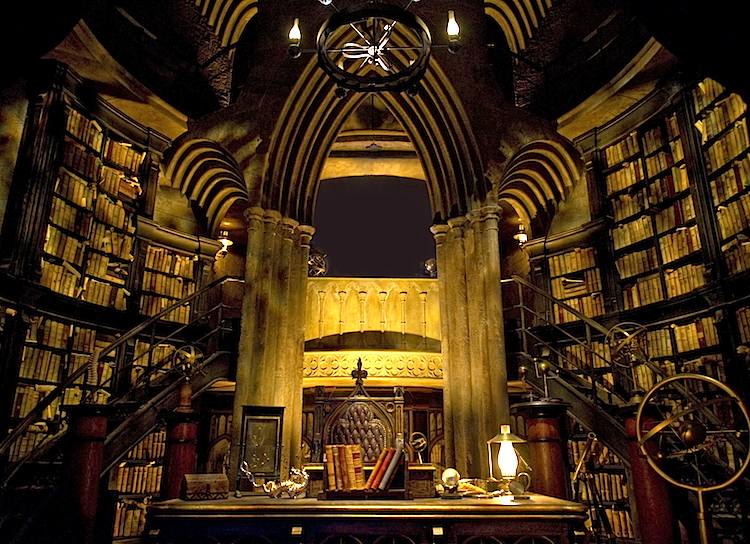

Movies like Star Wars or Harry Potter remind me of the famous ‘memory palace’ of Matteo Ricci, the 16th-17th century Jesuit scholar who went to China and instructed the Confucian elite in the art of memory. Ricci’s technique was to mentally construct an elaborate palace with many rooms, and in each room place a memory as if it were an artwork or piece of furniture. One sees echoes of this in the central edifice that looms large in the imagination of the Harry Potter series: the Gothic building complex of the Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. Hogwarts’ vast castle-like edifice is a kind of ‘memory palace,’ with its many rooms, galleries, and passageways containing treasures and secrets that make it a repository of the European historical and cultural tradition.

This tradition as it is referenced in Harry Potter includes the English Gothic romantic novel, the German coming of age novel or Bildungsroman (exemplified by Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister novels), medieval occult and alchemical lore, European Romanticism, and Greco-Roman pagan mythology – interwoven with concerns about the 20th century’s totalitarian mass movements.

And this is another point to make about the Harry Potter films: they present the Western religious and mythological tradition, but in an altered/cloaked form.

In the Harry Potter movies we get a melding of Christian and Greco-Roman mythology – the twin pillars on which rest the Western humanistic tradition – but cloaked in the outward forms and symbols of the ‘heretical’ or ‘ dark’ side of that tradition, which is witchcraft. It makes for an at times uncomfortable viewing experience, and is what makes me unable to wholly give myself to this series, however much I may like many aspects of it. (Full disclosure, I’m not a Christian myself, but I have tremendous respect for Christianity as a vital component of the Western tradition).

I know perfectly well what ‘witchcraft’ and ‘wizardry’ traditionally stand for, and it isn’t anything wholesome. And yet it seems that in a self-conscious, neurotic age that has trouble dealing seriously with themes of religious faith or romantic love, these themes must be disguised under the mantle of the occult in order to be acceptable to audiences. Just look at the Twilight series; it is the only major romantic film series in many years, but it has to be oriented around vampires and werewolves in order for its rather traditional love story to be accepted by modern audiences.

J.K. Rowling has herself stated that she is a practicing Christian, but that she deliberately downplayed any Christianity in the Harry Potter stories. Thus, in a movie series that is replete with every form of supernatural activity, there is a studious avoidance of any mention of a God or of a higher divine force. There are some hints in the films, but generally they’re in the background, and it makes this otherwise very detailed world seem incomplete. Witchcraft, sorcery, demons, goblins, and elves are the obverse side of the normative Christian tradition. With that normative tradition downplayed or taken out, it leaves a lot of unanswered questions in the Harry Potter films.

What higher spiritual dimension there is in the films is represented by the Gothic cathedral-like architecture of Hogwarts, by a magical deer of light that guides Harry, and by a heaven-like realm of light that briefly figures in the film. The main religious symbolism belongs, though, to the architecture of Hogwarts. For example, on several occasions when there are significant confrontations between good and evil in the film, the camera lingers on the Gothic arches or stained-glass windows of Hogwarts, with a soft light shining through them – as if to indicate the presence of a higher divine power.

One shot in particular, at a pivotal moment in the film, reiterates this. The shot is of a shattered Gothic building on the edge of the Hogwarts complex. It stands, with its arch still intact, against a silver grey landscape of hills and trees, with a lake in the distance, and a soft light shining down upon it. It reminds me of German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich’s famous painting The Abbey in the Oakwood (1809-1810), in which a ruined Gothic church stands in a snowy wood amongst black, leafless, wind-blasted trees. In this dismal scene, a soft light shines through the arch, coming from the torches of a group of solitary pilgrims. The church represents European Christianity, blasted by the storms of the Protestant Reformation and the French Revolution, but still standing, and still with a residual glow of vitality as long as there are worshippers left to believe.

Underneath these hints of Christian faith in the Harry Potter films, though, there is a chthonian, Greco-Roman pagan substrate. One sees this in the many scenes where characters travel down into the earth through secret caverns and passageways, encountering magical snakes or dragons who guard secrets or treasures. Early in the film Harry, Hermione, and Ron disguise themselves and make their way into the subterranean vaults of Gringotts Bank (a magical, goblin guarded bank) in order to break into the vault of the villainous Bellatrix, who has a piece of Voldemort’s soul hidden in a goblet that the trio must destroy. They make their way past a giant white dragon and walk into Bellatrix’s vault, which is full of golden treasure. However, a spell in the vault means that every piece of gold they touch will rapidly multiply and swamp them under. This is a clever re-envisioning of the ancient Greek tale of the greedy King Midas, who was given the gift of the golden touch by Bacchus, only to find that it would literally kill him by turning everything he touched to gold -including his food and drink. One also sees echoes of this in Rex Ingram’s film adaptation of Balzac’s novel Eugenie Grandet, in which the old miser who has destroyed his family out of greed for gold is in the end crushed by his chest of gold when it falls on him.

Snakes, the focus of numerous religious rites in Greco-Roman mythology, also feature throughout the film. For example, in a secret chamber underneath Hogwarts, there is the skeleton of a giant serpent, a basilisk, killed in an earlier film in the series. It is flanked by rows of rearing stone serpent statues, and is guarded by a door with multiple serpent locks.These snakes recall the many serpent deities of Greco-Roman mythology, lying as they do deep in the bowels of the earth.

For example, a chthonian, subterranean snake god was worshipped on Athens’ Acropolis, in a special temple to the god Erechtheus, close to Athena’s sacred temple the Parthenon. Snakes also played a central role in the rites of the Eleusinian mysteries, one of the ancient Greek world’s most important and revered mystery cults. And there’s the fact that in the final battle around Hogwarts, the characters use the teeth from the basilisk to slay the different parts of Voldemort’s soul that he’s hidden in the ‘horcruxes.’ These magical teeth recall the mythical tale of Jason and the Argonauts, in which Jason sows a dragon’s teeth in the fields of the sun and then battles the ‘earth-born’ men who spring up from them.

What brings all these mythological allusions to life in the film, though, is the casting – and it is in the warm, witty, colorful, and wicked characters of the film series that Harry Potter‘s humanistic appeal chiefly lies. Daniel Radcliffe, Emma Watson, and Rupert Grint are sympathetic as always in their lead roles as Harry, Hermione, and Ron. The real stand-outs, though, are the supporting characters, who are a veritable who’s who of the British stage and screen. Maggie Smith as Professor Professor Minerva McGonagall (again, note the mythological allusion to the warrior goddess Minerva) is my favorite character in the film. She is magnificent in the scenes at Hogwarts when, after having watched too much injustice take place, she finally steps up, sends one particularly villainous character packing, and leads the defense of Hogwarts against the forces of evil. Smith in these scenes is steely and dignified – but with a humorous sparkle that makes her a very appealing and inspiring authority figure.

My second favorite character would have to be the insane villainess Bellatrix Lestrange, played with daft glee by Helena Bonham-Carter, who joins Maggie Smith as being one of England’s great eccentric actresses. Michael Gambon also brings a nice warmth and dignity to his role as Albus Dumbledore. Another standout in the cast is Alan Rickman as Severus Snape, who reveals in the film new depths to his severe, saturnine persona. And obviously Ralph Fiennes as Voldemort can play these sorts of supremely villainous characters in his sleep, bringing suitable intelligence and menace to his role. The fine actors of England’s rich theater tradition are one of the great strengths of the Harry Potter films.

Overall, this final installment in the Harry Potter saga should make its fans very happy. The film wraps up the story in an emotionally satisfying manner and provides plenty of fantasy, action, and spectacle along the way. Now we just have to see which of the innumerable new fantasy series that are springing up in its wake will take Harry Potter’s place in the world audience’s imagination.

Posted on July 19th, 2011 at 9:42pm.

Excellent article! I have to admit that I’ve seen the things that you reference in all the Harry Potter books however I lack the depth of specifics to successfully convey such a detailed interpretation. What I can say is this is that I’ve enjoyed all the books as an adult and felt that all the movies with the exception of this one were dismal in comparison. In fact, I had grown to dislike the Potter movies to the point that I didn’t bother with the Deathly Hollows Part One. The previous Harry Potter movies seemed the reverse of this movie in that they focused on the teenage angst, puppy love angle to short shifting all the serious issues that the books dealt with or at best just seemed to mention in a cinematic sense.

I agree with you regarding Maggie Smith and Helena Bonham-Carter. In particular the scene of Maggie Smith facing down Alan Rickman reminded me of the scene from The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance when John Wayne faced down Lee Marvin in the diner. Truly electric and wonderful to see the thespians of the Potter series step forward and be featured more directly. I realize the three main characters were all children and all unknowns when cast ten years ago.(Dakota Fanning just doesn’t come along every day) Unfortunately the previous seven movies had to be carried by these actors and the producers were smart to surround them with such an outstanding supporting cast but ultimately and to degree expected the previous movies seemed watered down.

In the end this movie was satisfying and well done.

Thank you Johngaltjkt! I’ve seen the films but haven’t read the novels, so it’s interesting that they’re that different in tone. I wanted to deal with the movies on their own terms, so that’s why I also focused my piece on the visual symbols and allusions in the film. I’ve seen a lot of people write about the themes of redemption, love and forgiveness, etc. in the Harry Potter stories, but I don’t usually see people discuss the visual aspects of these films – the architecture of the films, the settings, the visual references to other cultures and historical periods, etc.

As for the supporting cast, yes, they’re absolutely terrific. That’s a nice comparison to the scene in “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance.” As you point out, the scenes where these very talented actors step forward and get to shine are truly electric. Honestly, I wanted to see more of them. In addition to Maggie Smith and Helena Bonham-Carter, I thought Alan Rickman was truly superb. He really knew how to bring out the doomed romantic in Snape’s character.

Never been a Potter fan but what an awesome article. Must of been fun to see Dame Smith kicking some butt, hee hee.

PS: I guess Carmageddon was not so bad because you were able to make it to a movie theatre, hee hee.

Thank you Michael! Yes, that was a great scene where Maggie Smith turns the tables on the villains. She’s a terrific actress and now I want to go and see some of her other recent work. I’m glad to see she’s keeping very active.

As for Carmageddon, it was completely overplayed by the LA media, as usual. They’re always looking for a crisis to hype, but apparently most people just stayed home and the streets were clear. Jason tells me the same thing happened during the ’84 Olympics when they were in LA.

Always interesting how these very distinguished British thespians seem at lot more willing to play roles in these tent pole movies. You have enough Sirs and Dames in the Potter series to fill an Arthurian round table. For some reason Americans actors/actresses of similar age and prestige turn their noses up on mass market movies.

I have had my issues with this site, as it basically turned into a Christopher Nolan hatefest last summer, and probably will do so again next summer. But this is still the best conservative film website around, and excellent articles like this are why. Your analysis, Govindini Murty, is spot-on, and a very welcome response to the unbelievably lazy, snide analysis of the films offered by the “conservative” Kyle Smith just a few days ago. Nice work. Just do not let this site become all Sarah Palin, all the time, like another conservative film website I could mention.

One question, one of my colleagues is insistent that the Harry Potter series is largely an update of the Arthurian legends. Do you buy it?

Sean – I’m glad you like the site and thanks for your comments on my article. We do our best to take films like “Harry Potter” seriously both because of the cultural phenomenon they represent, and also because we do feel that they make an effort to affirm the values we believe in, even if they are conveyed in a different outward form. As for Christopher Nolan, I don’t think Jason’s satirical review of “Inception” last summer constituted a ‘Nolan hatefest,’ but I guess we’ll have to agree to disagree. In any case, there are many other films we can agree on, and we do our best to cover those.

As for “Harry Potter” being a re-envisioning of the Arthurian legends, I think there may be some truth there. Dumbledore can be considered a Merlin-like figure, there’s an enchanted sword that plays an important role, and Harry is certainly on a quest to discover his destiny. The major difference would be that whereas the Harry Potter stories focus on Harry’s journey from boyhood to young adulthood, the Arthurian legends seem to center more on the story of the adult Arthur, his leadership of the Knights of the Round Table, the tragedy of his marriage to Guenevere, and the Grail Quest.

Although I enjoyed Inception, I actually thought Jason Apuzzo’s upside-down review was rather clever. It just seemed as if every other day he was reminding us how much he hated the film, it seemed a bit excessive.

(SPOILERS)

It would have been fascinating if Rowling had followed the Arthurian legend all the way through with Harry and Voldemort killing each other like Athur and Mordred. I actually thought the series was moving in that direction, but I suppose it would have been a but too much.

The success of the films is also remarkable given how so many of its imitators have fallen flat on their faces, none more completely than the His Dark Materials series, it testifies to the dramatic and thematic strength of the novels.

Keep up the great work!

This is truly a superb examination of the Potter series. You’ve caught a number of elements in the films I suspected were in there but didn’t bother to examine further. Like you, I haven’t read the books but have enjoyed the movies (some more than others, of course).

The enduring aspect of the Potter series for me is the struggle between good and evil, and how Harry and his friends have learned to grow and gain wisdom from life’s lessons to make the right decisions.

And thank you for introducing me to The Abbey in the Oakwood. That’s a marvelous painting.

Thank you Galt1138! I appreciate the kind comments. I think that struggle between good and evil is one of the major reasons for the popularity of “Harry Potter.” I think the films are really quite humanistic in how they portray friendship, loyalty, and sacrifice. I found it quite touching how in the final film so many of the characters make the brave choice to stand up for good, even when they are so apparently outnumbered by the forces of evil. It reminded me of that plucky British spirit that was exemplified in WWII films like “Mrs. Miniver,” in which average people were shown standing up for freedom against the Nazi war machine.

And I’m glad you liked “The Abbey in the Oakwood.” Here’s the Wikipedia page on Caspar David Friedrich with some more of his paintings. In my view he’s the preeminent Romantic painter, and has influenced the visual style of more Hollywood movies than I can count.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caspar_David_Friedrich

This superb article is the reason I read Libertas. I don’t often agree with Jason’s opinions on major blockbusters and I can get movie news faster from other sites, but when you guys want to give an intellectually serious analysis, no one else can compete. Keep up the good work.

P.S. Sorry for being such a grammar-nazi, but the words are spelled “horcruxes” and “Bellatrix.” I know, they’re made up words and you haven’t read the books, so I forgive you. But still. 🙂

Thanks Stephen – we appreciate your comments. When we re-launched Libertas we wanted to do exactly that – focus more on providing serious, thoughtful pieces that you won’t necessarily read everywhere else. That’s why we changed the focus to being more of a ‘magazine’ than a strictly ‘film news blog.’

And I’ve corrected the spelling on ‘horcruxes’ etc. in the article. It just goes to show you, as much as you make an effort to double and triple-check every name and fact, there’s always something that slips through – particularly when dealing with the terminology of these fantasy films.

Excellent essay, Govindini. I haven’t read the books, but when I taught high school composition I had to pry students loose from reading them so we could start the class! I wasn’t too hard on them though–I felt like the books and all the elements you describe were preparing them in a way for something deeper–thinking about such things like good v. evil and Western civilization.

That is simply a wonderful essay, Govindini — Joseph Campbell would be very proud. He described mythology as a “metaphorical language,” and I think this article expands on that concept, and illustrates why it is so important.

I’ve read some of what J.K. Rowling has said on the Christian element in her work, but I think it’s oddly fitting considering Harry’s arc is basically a St. George allegory. Since very early Christianity is intertwined with history of the occult, and St. George’s journey was said to take place in that timeframe, this approach works — especially if you consider Voldemort as the dragon.

St. George’s victory paved the way for many to convert to Christianity, but as we’ve seen in history, every blossoming religion has adopted elements (many times alchemy and the occult) of the previous one into its formative stages.

Considering the end of Harry’s arc, I would think sequels in the Harry Potter universe would naturally feature an expanded role of Christianity.