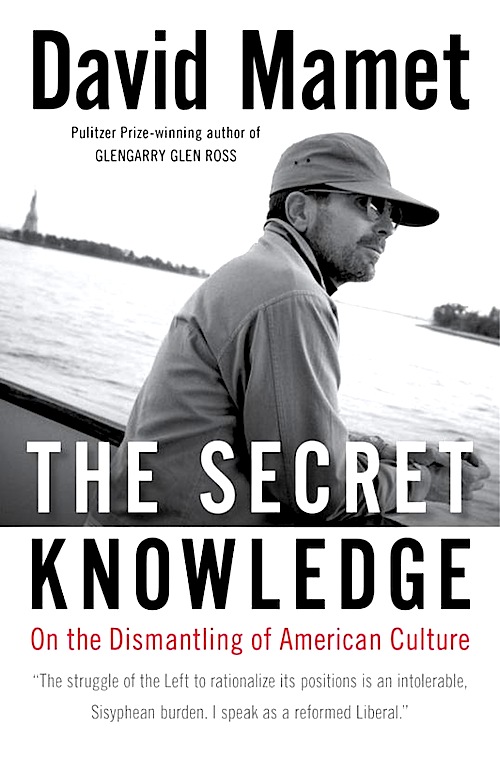

By David Ross. I wrote a while ago about David Mamet’s splashy conversion to conservatism (see here), about which I was naturally excited, Mamet being the highest ranking defector in the modern Cold War between right and left. I eagerly awaited his book, The Secret Knowledge: On the Dismantling of American Culture, hoping for a manifesto that would function as an elegant rapier thrust, or at least a solid groin kick, and hurt all the more coming from a man whom the left cannot write off as a cretin from the land of “low-sloping foreheads” (to borrow a phrase from New York Times columnist David Carr). Mamet has, after all, lent intellectual heft to Broadway and Hollywood for more than three decades.

By David Ross. I wrote a while ago about David Mamet’s splashy conversion to conservatism (see here), about which I was naturally excited, Mamet being the highest ranking defector in the modern Cold War between right and left. I eagerly awaited his book, The Secret Knowledge: On the Dismantling of American Culture, hoping for a manifesto that would function as an elegant rapier thrust, or at least a solid groin kick, and hurt all the more coming from a man whom the left cannot write off as a cretin from the land of “low-sloping foreheads” (to borrow a phrase from New York Times columnist David Carr). Mamet has, after all, lent intellectual heft to Broadway and Hollywood for more than three decades.

It pains me to confess that Mamet’s book is dreadful. It’s not, as one might imagine, that his conservatism turns out to be a smug centrism in the David Brooks mode or an idiosyncratic wire-drawn intellectual construct in the Hitchens mode. On the contrary, he shares the talk-radio mindset of bitter far-right disgust, and he seems sturdily committed to the entire Republican platform, for better and for worse. Conservatives will immediately recognize Mamet as their man.

The problem is twofold: 1) What seems to Mamet revelatory a year or two into his conservative phase is not so revelatory to those of us who’ve spent twenty or thirty years toiling in the conservative vineyards. He’s like a blind fellow who can suddenly see and proceeds to inform everybody that the sky is blue and the grass is green and chesty women look good in tight sweaters. 2) The book is badly argued (where it’s argued at all) and badly written in the basic mechanical sense. Mamet’s prose is gnarled and parenthetical and weirdly affectless (c.f. his nerveless, deadpan directorial style). It’s not as bad as Sean Penn’s prose, which is almost literary anti-matter (see here), but, lord, it ain’t good. Here’s a sample, cherry-picked only slightly:

If a country, a region, a race is in difficulty because of a lack of funds, any new or recurrent failure subsequent to any subvention in aid may be attributed to insufficient aid, and provide the rationale for that funding’s increase. But it may only do so given the acceptance of the nondemonstrable, indeed disprovable theory that government intervention increases wealth. (pg. 36)

This is to say, more or less, that governments like to throw good money after bad. I can only suppose that writing street-smart dramatic dialogue and writing elegant expository prose are entirely different skills, and that Mamet is a writer only in a restricted sense.

Bloodying his claws in The New York Times, Hitchens delivers a predictable and reasonably fair evisceration. Hitchens is himself a splendid stylist whose own writing is not here at its best. Unlike Mamet, he has the excuse of being on his literal deathbed. Hitchens notes the elusive significance of Mamet’s title, and I second his confusion. It’s not clear what this “secret knowledge” entails or to whom it belongs or in what sense it’s secret. “There is no secret knowledge,” says Mamet. “The federal government is merely the zoning board write large.” Your guess is as good as mine.

Mishap of a book aside, I’m glad that Mamet has seen the light. It means that there’s a light to be seen and that it penetrates deep into liberal redoubts. I would like to see Harold Bloom and Philip Roth likewise make autumnal conversions. Grumpy Jewish mandarins steeped in the history of literature and philosophy and deeply nostalgic for the pre-lapsarian fifties are by definition ripe for the plucking.

P.S. Let me respond to Carr’s crack about “low-sloping foreheads.” No matter how often I encounter this kind of snobbery, I’m shocked by its rancidity and by its small-hearted repudiation of America in its breadth and width. What would Walt Whitman say? What would Woody Guthrie or Pete Seeger say? This is ignorant in so many ways: ignorant of the rich life that exists everywhere as a function of intrinsic creative and organizational impulse; ignorant also of the basic American cultural dynamic, by which, over and over again, Wordsworth-like figures emerge from provincial obscurity to center our history. Abraham Lincoln was, you might say, from the Land of Low Sloping Foreheads; so too John Coltrane, and Flannery O’Connor, and Thomas Wolfe, and Bob Dylan, and many thousand others. The matrix of American culture is essentially dependent on this encounter between local folkways and experiences and cosmopolitan forms.

Carr’s chief resume point, by the way, is that he used to be a cocaine addict and wrote a memoir of his experiences. I’m not sure why this makes him an authority on the mental capacity of other people. People in Sioux City for the most part know that cocaine is bad for you and for the most part manage to stay out of the gutter, which is more than Carr can say for himself.

Posted on July 14th, 2011 at 9:45am.

Too Bad…could have been ahh contenda

The disappointment, the disappointment. A great screenwriter, but alas not a P.J. O’Rourke. The medium is everything and perhaps Mamet is not yet familiar with it? I have a feeling this will not be the last time we hear from him.

David – I read a few chapters of Mamet’s book and came to much the same conclusion. I have to say that Mamet is at his best when he is telling stories. He did some very funny interviews with the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal where his humor and storytelling really comes through. I wish the whole book had been like that.

I really enjoyed the book, but not in the same way I enjoyed Mark Levin’s “Liberty and Tyranny,” for example.

Mamet’s book was interesting because it conveyed the energy and mental frenzy (whether intentional or not) of someone who realizes that modern American liberalism is a huge fraud based on emotions, and that conservatism is an intellectual pursuit.

Mamet’s prose in this book reads like that of a reformed liberal, or someone mocking that way leftist politicians talk and write bills. I’ve found that leftists use that tactic, so they can me ambiguous about explaining themselves or interpreting laws.

I’ve knows a few leftists who broke from their overlords and the church of global warming, and they talk just like Mamet in this book.

So, to me, the book’s value comes from getting a glimpse into the mind of someone who came to some big realizations in his life. In this case, it’s a genius writer who was the darling of the NYC cocktail liberal crowd.

I’ve heard this reaction from some other conservative/libertarian reviewers. I’ll have to read it and make my own judgment. But, if true, it’s unfortunate.

Mamet’s written some wonderful non-fiction stuff. His various essay collections entail a variety of subjects, all displaying his skill, intelligence, brevity and clarity of mind.

If this book is indeed poorly written, please don’t assume Mamet can only write plays and screenplays. Check out The Cabin, Some Freaks, South of Northeast Kingdom, Make Believe Town.

His movie/entertainment industry specific books are also quite good: On Directing Film, True and False: Heresy and Common Sense for the Actor, Writing in Restaurants, Three Uses of the Knife: On the Nature and Purpose of Drama and Bambi vs. Godzilla.