By David Ross. Every so often liberal big leaguers take a whack at Thomas Kinkade, the king of mall and mail-order art, the entrepreneurial painter laureate of what Jed Pearl calls “Wal-Mart America.” His depictions of gingerbread cottages nestled in what seem to be sleepy Cotswold hamlets are beloved by the masses and equally detested by people who consider themselves – by virtue of college degrees and the occasional glass of white wine with dinner – Blue State sophisticates. In 2001, Susan Orlean gave Kinkade the once-over in the New Yorker (see here), though she semi-restrained her snark on the grounds that Kinkade’s buffoonery speaks for itself. Pearl has now followed suit with an inchoate piece of hostility – titled “Bullshit Heaven” no less – in The New Republic. Extending the toilet metaphor, Pearl concludes that Kinkade has “urinated on us all.”

There’s no denying that Kinkade’s art is pure kitsch, a confection of Christmas-card nostalgia derived from Wordsworth at his most fey, Norman Rockwell at his most precious, and whoever first had the idea of painting and mass-producing scenes of beagles playing poker. His cotton-candy shire scenes look as if model trains should be running through them or Hobbits should be peeking from the windows. I would no more hang a Kinkade in my living room than a poster of Ashton Kutcher in the buff.

The blame is usually – okay, always – directed at putative yahoos who clamor for this kind of thing and create demand for what were better handled like dog poo in the street (quick condescending glance, wide berth). Articles about Kinkade are never really about Kinkade; they are about the people who buy Kinkade. Essentially, they license the readers of the New Yorker and The New Republic to look down on “Wal-Mart America” from a standpoint of cultural and aesthetic superiority. Their real substance, in other words, is Blue State-Red State politics.(I wonder, by the way, whether a film like Winter’s Bone doesn’t exploit the same condescension.)

In their eagerness to stroke the coastal ego, these pieces miss the real story, which is that “Red State yahoos” positively clamor for art. As someone observes in the Orlean piece, “Thom will go to a gallery, and twenty-five hundred people will show up. He speaks for about thirty minutes, and afterward they come up to him a talk. It’s very emotional, some of them are crying and saying, ‘Here’s how you have affected me.'” The real story is not that Kinkade has filled a vacuum (nature abhors a vacuum, as we know), but how vast the vacuum turns out to be and how it became a fact of our cultural life in the first place.

The fault does not lie with Kinkade or his aesthetically parched and panting clientele, but with the coastal art establishment – the museums, the universities, the galleries, the publishers, the artists themselves – which self-consciously punctured the legitimacy of the romantic, the humorous, the picturesque, the narrative, the historical, and the instinctually lovely, and thereby destroyed everything that could possibly give pleasure to an ordinary person. The Kinkade phenomenon did not coalesce because people are irremediably stupid, but because real artists stopped doing their job, which is to excite the imagination.

As late as the first quarter of the twentieth century, American art was dominated by artists who might well have appealed to the Kinkade audience: George Innes (1829-1894), J.M. Whistler (1834-1903), William Merritt Chase (1849-1916), Thomas Wilmer Dewing (1851-1938), John Henry Twachtman (1853-1902), John White Alexander (1856-1915), Childe Hassam (1859-1935), Edmund Tarbell (1862-1938), and a host of lesser painters – thousands of them – who made their modest livings helping the middle-classes beautify their parlors with scenes of orchards and harbors and young lovers chatting by the stile. Where are their like now? Mall galleries sometimes sell traditional landscapes, but these are so bland and amateurish and expensive that it’s no wonder the art-starved masses flock to Kinkade. He at least has a kind of vision, a certain insinuating emotional fixation.

As late as the first quarter of the twentieth century, American art was dominated by artists who might well have appealed to the Kinkade audience: George Innes (1829-1894), J.M. Whistler (1834-1903), William Merritt Chase (1849-1916), Thomas Wilmer Dewing (1851-1938), John Henry Twachtman (1853-1902), John White Alexander (1856-1915), Childe Hassam (1859-1935), Edmund Tarbell (1862-1938), and a host of lesser painters – thousands of them – who made their modest livings helping the middle-classes beautify their parlors with scenes of orchards and harbors and young lovers chatting by the stile. Where are their like now? Mall galleries sometimes sell traditional landscapes, but these are so bland and amateurish and expensive that it’s no wonder the art-starved masses flock to Kinkade. He at least has a kind of vision, a certain insinuating emotional fixation.

Who can blame people for despising and ignoring the kind of leftist political cartoons and sexual grotesquerie and trashcan assemblages that pass for art in the schools? Who can blame them for turning to Kinkade as the only accessible antidote to all this repulsive silliness? To my mind, Kinkade’s audience comes off rather well, even heroically. Denied outlets for their legitimate aesthetic instinct – ridiculed, fleeced, bombarded with alternate media – they still muster their hard-earned dollars and cents to purchase art that identifiably (if degenerately) belongs to the great tradition of Western imagination and representation.

Kinkade instinctively understands and exploits these cultural dynamics. He says in the Orlean piece,

The No. 1 quote critics give me is “Thom, your work is irrelevant.” Now, that’s a fascinating, fascinating comment. Yes, irrelevant to the little subculture, this microculture, of modern art. But here’s the point: My art is relevant because it’s relevant to ten million people. That makes me the most relevant artist in this culture, not the least. Because I’m relevant to real people. [… ] We’re the art of life, man! We’re bringing the life back to art! [… ] The fact is we have a grassroots movement emerging in my art and in the country, and there’s ten million people out there that if I give the word will go out and picket any museum I want them to. I won’t give the word, but they’re dying to have an art of dignity within our culture, an art of relevance to them. Look at someone like Robert Rauschenberg. What’s his Q rating? How many people have his art? A hundred? Where is the million-seller art? What about the craftsmanship of expression?

Kinkade and his ilk do not however represent a genuine solution to the problem; they merely manifest the perversity of the situation. One source of tentative hope is Art Renewal, a well-funded and combative organization run by New Jersey millionaire Fred Ross (no relation, unfortunately). Art Renewal is fighting an intelligent rearguard action not only against post-sixties art (my own rearguard action) but against post-Victorian art. It organizes classes in representational drawing, hosts contests and competitions, sells traditional fine art prints (a good alternative to Kinkade), publishes books, and provides on-line access to a cache of 63,000 digital images, making it an important resource whatever one thinks of its philosophy. I can’t imagine how it assembled such a vast digital archive and how it acquired permission to disseminate images of paintings belonging to museums like the Louvre. (For another very impressive cache of digital images, see the BBC’s new “Your Paintings” feature).

Art Renewal’s enthusiasms may be a bit musty, but it understands what’s happened and what must be done. It has a clear picture of the battlefield and apparently enough money to dabble in ballistics. It’s a David and Goliath situation, but we know how that little scuffle turned out.

Posted on August 12th, 2011 at 11:42am.

Great article David!! Many modern artworks simply don’t appeal to the masses in the way that Impressionists do for example. Modern art is more about provocation and “truth,” and less about beauty.

If it makes one less sophisticated to like a Kinkade or Norman Rockwell, so be it.

I always thought Kinkade was one of our finest postmodern artists – ironically skewering low brow representational art ( the kind Hitler liked ! ) with his oh so precious depictions. His doctrinal error was taking money from the middle class while not making it clear how much he hated their “discrete charm”.

/Sarc off

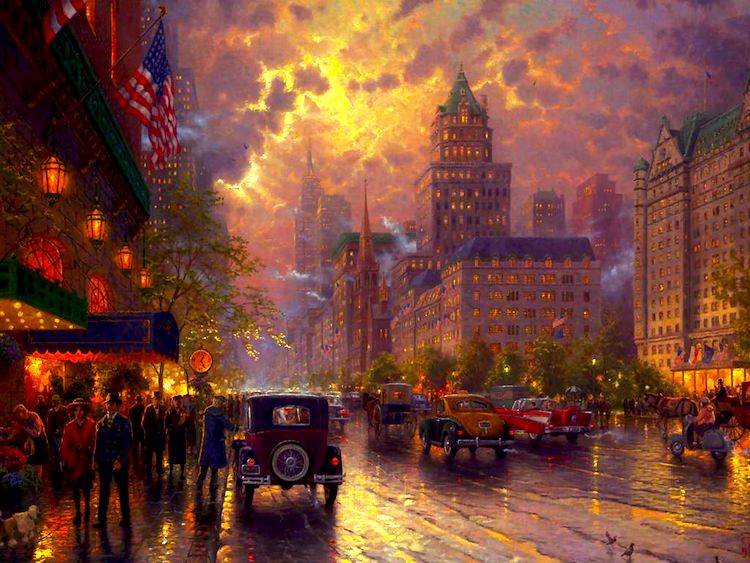

I don’t know, take the first picture you chose to illustrate your piece: it shows 5th Avenue on fire, while the people of Manhattan go about their business as if nothing is happening. A comment on the debt situation, perhaps?

Greart article. I would not hang a Kinkade but I would not blow a single dollar on any post-WW II artist.

Just to comment on Anton’s post. The Impressionists were widely panned by the art critic community of their time, although Zola was a very vocal defender, for the reasons you mention. Although of course they have withstood the test of time.

One hopes that at least some of those who now spend fairly large sums buying Kinkade kitsch will notice your article and spend much less money on the quite good prints now available of representational art. For example, the Kinkade mountain scene shown above is a really outrageous imitation of Bierstadt; how easy it now is to get a decent print of a real Bierstadt landscape! (P. S.: Anton above mentions Kinkade and Rockwell together. They are most certainly not the same, thank you very much!)

I’m partial to the works of Frederic Remington, myself, but I’m silly that way.

Idyllic and tranquil is what humanity has longed for since the beginning. I believe it is the sign of a healthy and compassionate soul. It is antithetical to the demonizing ‘thumb in your eye’ pornography so prevalent in modern imagery embraced by many priggish, urban, liberal-progressive, pseudointellectual snobs.

I’ll enjoy Kinkade, anyday. I’m simple that way.

Thank you, Mr. Ross, for a very good read, although I don’t believe that “turning to Kinkade” is the only accessible antidote for the masses. Or perhaps that was a metaphor.

I think the landscapes are dreadful, but the city scene is kind of neat.

Art (and often movie) critics are compelled to despise anything widely accessible. People should buy the art that pleases them, and kudos to him for being a success (although I don’t think he actually paints any of it himself anymore except a brushstroke or two), but I do think his art is rather hideous, but I may be biased because I just got back from New York and lengthy sojourns in both the Metropolitan Museum and the Museum of Modern Art. Give me an O’Keeffe any day. I do think you mischaracterize “Winter’s Bone,” though. I don’t feel it was treated condescendingly at all. It was a damn good movie about a seldom seen side of America, and I think viewers and critics took it that way.

It seems to me that Winter’s Bone largely portrays the Ozark folk as meth freaks and coke-heads, flinty but essentially dysfunctional and violent. The film may or may not accurately reflect life in the Ozarks, but I doubt the writer/director, Debra Granik, knows much about it. According to Wikipedia, she grew up in Cambridge Mass. and the suburbs of Washington D.C., which are about as far from the Ozarks, culturally if not geographically, as you can possibly get. I suspect that someone who actually lives in the Ozarks might object to this representation of friends and neighbors. I may write more about this later. Stay tuned.

Winter’s Bone the movie is pretty faithful to Winter’s Bone the book, only less gritty. The movie’s director may not know much about it, but the author of the book, Daniel Woodrell, most certainly does. He’s from the Ozarks and I believe still lives there.

I just clicked over to Kinkade’s gallery site; it’s interesting, the coloring of the Fifth Avenue street scene depicted above is far different on his site. The fiery oranges and yellows are absent; the shades are muted. What’s the source for your version?

Here’s the Kinkade link:

http://www.thomaskinkadegallery.com/store/index.php/images-gallery/city-and-street-scenes/new-york-fifth-avenue-2003.html

I agree with your article however not with your reference to Winter’s Bone. First, Kinkade is not my preference in art but I do not begrudge anyone that enjoys it. It has a familiarity that I grew up with from my youth in Kentucky. Now back to Winter’s Bone. I believe a more apt movie to reference would be American Beauty. I can’t think of a more vile put-down of red state America than that movie.

As I mentioned I’m originally from Kentucky and a large part of my family is from Eastern Kentucky. The area and the people depicted in Winter’s Bone is very similar. Nearly fifty years and probably a trillion dollars from the Great Society has done nothing but taken proud hardworking people and turned them into government teat sucking zombies. Eastern Kentucky like the Ozarks is a geographically isolated area that offers virtually no opportunities of any sort and that’s even before the intervention of The Great Society. Then combine the plague of meth and it’s not hard to imagine the storyline of Winter’s Bone’s being repeated in real life.

John Galt (love the moniker),

Thanks for providing some empirical testimony. I’m willing to take your word for it. My skepticism stems from my own experience as a New Englander who moved to the South and discovered that the entire arsenal of anti-Red State generalizations are at best problematic, at worst purely fictitious.

I couldn’t agree more.

Yeah, I come from Southern Indiana, not quite the same area but rather close. My town is a college town, and has plenty of highly erudite people and worthwhile culture to be found if you look. But you go outside the city and into the country, and things are different. On the one hand, you might meet an elderly couple who can talk with you for hours about their lives, God-fearing folks who speak the language of the land. On the other, you might venture into, say, Greene County, and find raspy dull-eyed men dragging their heavy, unwashed wives after them, cussing back and forth without a care for their surroundings. Stories of meth dealers being caught or blowing themselves up are common, and the pictures in the paper look exactly like the characters in the movie. My mother did social work out there for a while, and she said she recognized these people from the movie immediately. The country certainly has its charms–just venture to any local county fair, and you’ll get a good taste of “real America”–but it’s not hard to find the dark side. I found the movie to be excellent.

This post and your previous post about graffiti, reminded me of an article in “Reason about the backlash on postmodernism i artists’ circles. Don’t know if that still stands.

Mr Ross, Ms Murty whats your opinion on the series White Collar with all the art and other better things they feature?

I will have to put White Collar on my list. Thanks very much for the advice.

I’ve never understood about the concept of ‘kitsch’. What makes something kitsch? Cliche? Beauty?

If I paint a picture of a basket of kittens, and no-one else in the culture is painting kittens, isn’t that bold and original? Kittens are beautiful. Isn’t that an eternal value? Why am I supposed to shudder? Isn’t gratuitous ugliness or surrealism the new kitsch?

Those pictures – the first seems slightly too derivative of some old painter I ought to be able to name. The second, the waterfall’s slightly too garish, like something off a fantasy novel cover. I’m not sure about some of his colouring. But I wouldn’t be too unhappy to live in a room with one of them on the wall, and if you’d told me they were by an OK name I wouldn’t have to work too hard to be enthusiastic. They don’t raise my hackles. I sort of like them.

I’m not a yahoo. I watch French films, I read hard books, I swoon if someone mispronounces a foreign word. I quite like Rauschenberg. I’ve read Arendt on Hermann Broch to try to understand about kitsch. I just don’t get it.

I’m not sure about some of his colouring.

I don’t know about the landscapes, but the coloring in this version of the city street scene is definitely off. It’s much more muted on Kinkade’s site, sort of a greyish scene of a rainy city street. I provide the link in my comment above.