By David Ross. Over two years, my nearly-six-year-old daughter and I have blown through all of Narnia, all of Harry Potter, and nearly all of Phillip Pullman’s great Dark Materials trilogy. She was attentive to Narnia and delighted by Harry Potter, but Pullman has entranced her to the extent that her face goes long with shock and anguish when I close the book and tell her to shout down the stairs for her nightly cocoa. Our next adventure is The Hobbit and its sequels. After tramping the roads with Frodo for six months, she will be primed for The Odyssey, beyond which lies the great Western sea of literature in all its dimensions of imagination and idea.

This program depends on the strict suppression of competing media (broadcast television, computer games, and web-surfing are verboten) and the realization that kids are by nature imaginative and that all attempts to subordinate the imagination to didactic and activist aims will produce a backlash of reluctance and indifference. Heather has two mommies, you say? This is a curious detail, worth a question or two, but not conducive to make-believe games or ruminations in the dark of bedtime. How much better if one of Heather’s mommies were a reincarnated Egyptian princess or a fairy queen cruelly trapped in a mortal body. This is not a political or literary judgment, merely an observation about developmental psychology.

Barbara Feinberg’s useful memoir of her kids’ reading, Welcome to Lizard Motel: Children, Stories, and the Mystery of Making Things Up, elaborates much the same point. Her basic thesis is that kids resist reading because contemporary books are insufferably pedantic and boring. This assumes that kids still read books at all. These days, schools seem happy enough to replace books with assorted ‘educational materials,’ not realizing or caring that these have all the romantic resonance of the suburban office parks where they were developed.

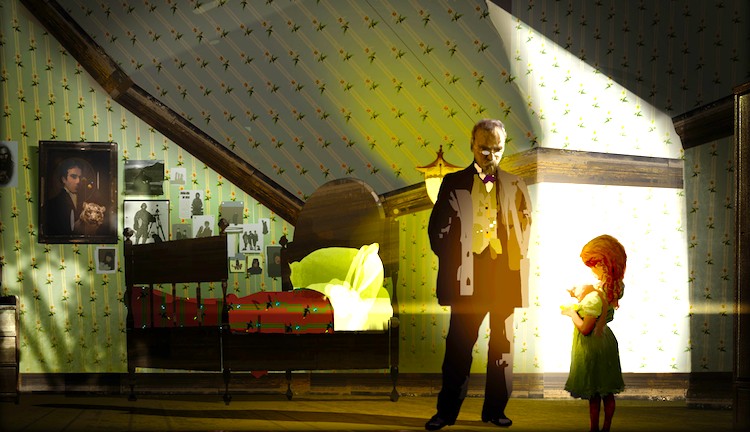

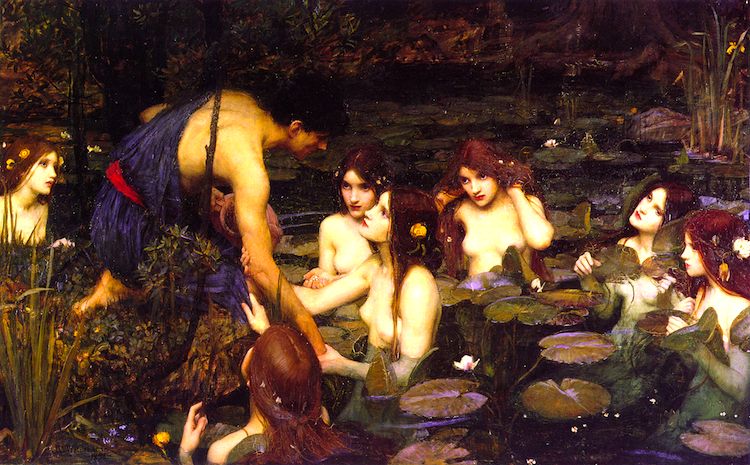

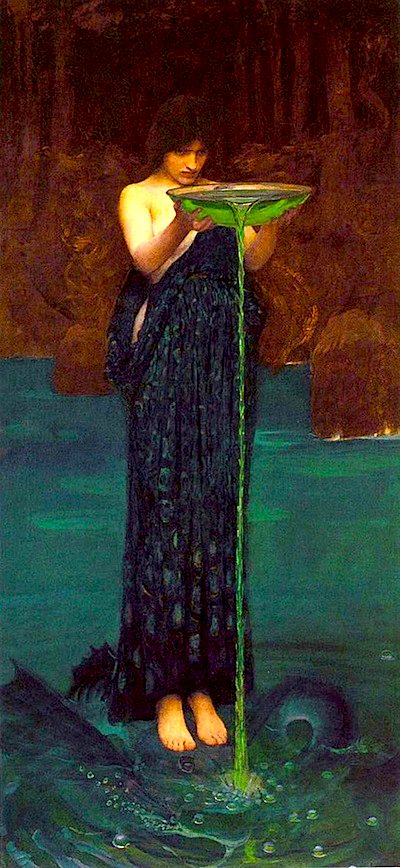

With the right bait, the fish is easily hooked. Not long ago my daughter happened to look over my shoulder as I perused a book of paintings by J.W. Waterhouse, the pre-Raphaelite master. She drank in the scowling witch (Circe) and the dead lady in the snow (St. Eulalia) and the beautiful lady in the boat (the Lady of Shalott) and the young man saying hello to the beautiful water fairies (Hylas and the Nymphs). These are images to trigger reactions in recesses of the brain not usually exercised in school, in comparison to which the images of her everyday visual field – all those bright socially aware posters in the hallways, for example – are pablum. She added the Waterhouse book to her “birthday list,” which in our house is the ultimate form of canonization.

Could it be that kids are so urgently programmed to decode and master their physical and social environments that they need periodic escapes in order to restore themselves, just as we must dream each night? Or is it the case that poetry and myth discern the essence of reality, and kids naturally respond to this brute explanatory power? These are unanswerable questions. What matters is that we take care not to trample or ignore what seems an elemental childhood impulse. Traditionally, children learned Bible stories and Greek myths. Whatever may have motivated these emphases, they gibed perfectly with the natural tenor of the child mind. Today, the focus is on composting and recycling and the more editorial episodes of American history.

Among literary doomsayers, some hold that there are no longer writers, some that there are no longer readers. My own sense of apocalypse conflates these positions: as literature becomes more fixated on the neurasthenic attenuations of domestic life, readers of normal blood become less interested. But wait! Along come the likes of Rowling and Pullman. Suddenly the next generation of readers and writers seems on the verge of flickering awake. There is a certain mounting hope and excitement … and then everything goes hideously wrong: Hollywood buys the rights, concocts a script, and it opens on 3,000 screens. There are commercials, lunchboxes, action figures, cover stories, documentaries, Academy Awards. Millions of kids get the message: the word is merely a gestating image, caterpillar to the film’s butterfly.

I particularly lament the screen adaptation of Pullman’s The Golden Compass, the first book of His Dark Materials sequence, the full trilogy being possibly my favorite contemporary work of literature, with competition only from that tender and oddly wizened genius David Foster Wallace. Pullman’s remarkable novels are the richest invitations to the childhood imagination. Why should Hollywood do the imagining for us? Lyra Silvertongue – a character to stand with Huck Finn and Jim Hawkins – will be fixed in the image of Dakota Fanning, and we will never love her in the same way – our own way – again. You doubt this? Here’s a quick test … Ready … 1, 2, 3 … FRODO! What came before your mind’s eye? I bet it was Elijah Wood.

I equally rue the recent screen adaptation of Ramona and Beezus. Beverly Cleary’s books are accessible, charming, and true to life, and constitute an invaluable invitation to what we call ‘big girl reading.’ In its devouring tendency, Hollywood has sabotaged a mechanism of literacy that has been importantly functioning for nearly sixty years. Poor Beezus’ fate is even more monstrous than Lyra Silvertongue’s: Dakota Fanning is one thing, Selena Gomez another.

It’s true that Hollywood has a long history of adapting children’s literature (The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Treasure Island, Pollyana, Mary Poppins), but in the fifties and early sixties – the golden age of children’s film – movies were less likely to upset the healthy balance between word and image, being confined to Saturday nights at the theater and lacking the nefarious seduction of CGI. Today, movies have infiltrated the classroom, the phone and computer, the backseat of the minivan. It’s also true that films sometimes generate interest in books and even return books to the bestseller list decades after their publication. The hype soon wanes, however, and people opt for the film because it offers a less difficult, more immediate pleasure, and because few recognize a cognitive distinction between reading and watching.

The basic problem is that Hollywood ever more rapidly and effectively co-opts the kind of books that should be seeding the next generation of readers. Having seen the movie, children come to the book knowing the plot and having had the characters and scenes already imagined for them. The magical immersion in the story is no longer entirely possible. There are not so many children-grabbing books that we can afford this kind of squandering of opportunity.

Why do books matter so particularly? Why aren’t they fungible? The answer is that they encode the language of the culture – not of pop culture but of Western culture – and the language of certain great questions that we must all eventually ask and try to answer.

Posted on June 1st, 2011 at 12:06pm.

I like your reading program, but I wonder if some of these works aren’t a bit wasted on a 5-year-old. They would affect a child differently – more deeply – if read a few years later, but they will already be known to her then. I was introduced to Tolkien in the 8th grade. Any younger, I think, and I would not have appreciated him properly. But I’m a re-reader, and I’ve read him many times since. Perhaps your daughter will do the same. BTW, I, at least, do not think of Frodo as Wood, nor of Gandalf as the actor who plays him, and certainly not of Aragorn as Mortensen. I have other, nobler, images burned into my brain from an earlier time.

I don’t consider Harry Potter nearly the equal of the other works mentioned, not Pullman’s, not Lewis’s, and certainly not Tolkien’s. After Azkaban, the writing and plotting went downhill. The last couple of volumes I skimmed rather than read, bored beyond belief by the endless foot-dragging and unconvinced by the just-so contrivances. Having invested all that time in the series, though, I wouldn’t quit until done.

Kishke,

Thanks so much for your comment. It’s true that a five-year-old necessarily gets less — or rather something different — from a work of literature. I don’t worry in the least about this. The goal is less to extract mature meaning from these works than to acculturate kids to the act of reading and the language of real books, so that when they finally encounter the brain damaged popular culture it seems to them alien and inferior — weird to them in the way that books seem weird to most kids.

I agree, by the way, that JK Rowling loses her footing toward the middle of her series, but I think she recovers somewhat toward the end. Her prose is far from impeccable, but she has a splendid sense of humor, an enormous capacity for invention, and almost Victorian sense of value (physical courage, loyalty, self-sacrifice, etc.). I’m encouraged by her enormous popularity, where nearly ever other cultural sign is cause for dismay if not despair.

to acculturate kids to the act of reading and the language of real books

Yes, this. We don’t have TV, and videos are allowed only on school holidays and subject to parental approval, so my kids are protected from the awful stuff that passes for kid’s entertainment today. The only time they get to watch TV is at the hotel when we’re on vacation. They are glued then to the Disney channel, noisy and dumb. I don’t see the appeal.

I haven’t had access to broadcast television since I was a teenager in the early 80s and my daughter has seen no television whatsoever. This is my simplest but most important piece of advice for parents: get rid of the TV. I don’t mean ration TV. I mean eliminate it entirely. It does nothing but poison a household with moronic noise and depressing emptiness. The very few good things on TV are obviously available on DVD.

It was Dakota Blue Richards who played Lyra.

Wonderful post, Mr Ross. You bring back memories of how my mother was a wonderful reader and selected lovely, although a tad didactic, books to read to me when I was small. I, myself, had a whale of a time selecting prose and poetry to read to my teen when he was a small boy with a wonderful imagination and a thirst for story. We, still, will get lost together in the right story on audio while traveling to various schools, appointments, sports, etc. I have even hooked his carpool buddy on Asimov, Heinlein, Pratchett and more.

The point of my comment is to agree with you that film adaptations can rob and flatten story and character. For an interesting take on this, there is an author comment, by Orson Scott Card, on one of the “Ender” audio books – it was either “Ender’s Game” or “Ender’s Shadow” I believe. In the comment the author discusses his feelings for story versus film. He is less than amused when a reader feels it is high praise to suggest that his book will make a tremendous movie. No, he doesn’t view this as high praise at all.

I really enjoy books from the 1940’s — “The Avion my Uncle Flew” by Cyrus Fisher and, for small children, I adore the “little Tim” picture book stories by Edward Ardizzone – you may too.

If you want a series (and what a series, it seems to have infinite titles) with transcendent imagination that has not fallen into film neverland, fall into the Discworld series by Terry Pratchett.

Keep on reading great works to your little girl. She is wildly lucky to hear these stories.

He is less than amused when a reader feels it is high praise to suggest that his book will make a tremendous movie. No, he doesn’t view this as high praise at all.

And yet, “Ender’s Game” is slated for release on film. I have mixed feelings about it. I would not like to see the story ruined by inept filmmaking, but if they do a good job, I wouldn’t object, especially considering that Card himself has sucked the life out of the Ender story with his endless alternate-point-of-view sequels. He should have stopped after Ender’s Game, or, failing that, after Xenocide.

If you’re a Card fan, I have a recommendation – “Lost Boys” – an affecting novel that, it seems to me, is not very well known.

Believe it or not, but I don’t think of Elijah Woods when I think of Frodo. I read Lord of the Rings twice before the films were released, so I don’t think the images my mind conjured of all things Middle Earth can be changed — especially since the films are so different in tone and structure from the book.

You hit on some interesting thoughts, Mr. Ross. I just think that literature is such a powerful engine for the imagination that no film can replace images one has created reading a book.

This point you made was especially astute: “The answer is that they encode the language of the culture – not of pop culture but of Western culture – and the language of certain great questions that we must all eventually ask and try to answer.”