By Joe Bendel. They are the dregs of society. Scorned and maligned, they live a dangerous existence in crude shantytowns as they pursue their quixotic quest. They seek redress from the Chinese government and for filmmaker Zhao Liang, these “petitioners” are his country’s greatest heroes. The product of over ten years spent with these marginalized justice seekers, Zhao’s Petition stands as arguably the most damning documentary record of contemporary China to reach American theaters since the initial rise of the Digital Generation of independent filmmakers. A special selection of the 2009 Cannes Film Festival, Petition finally opens in New York this Friday at the Anthology Film Archives.

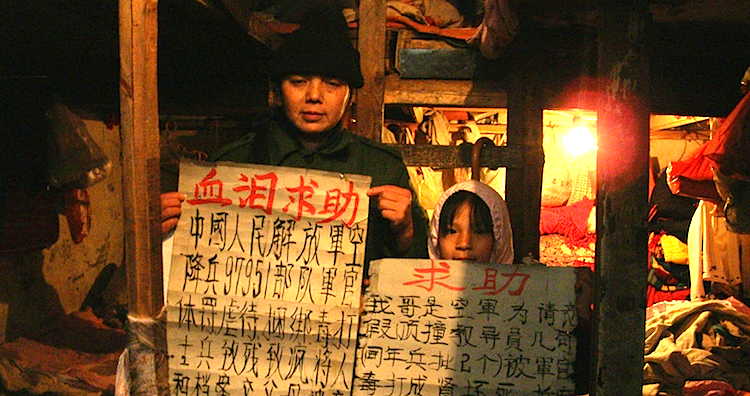

Throughout Petition it is crystal clear that the Chinese government has institutionalized corruption and hopelessly stacked the deck against the petitioners. Those victimized by unfair rulings have limited options locally for appeal (from the same corrupt bodies), so their only recourse is through the Kafkaesque “Petition Offices” in Beijing. Never in the film do we see the bureaucrats there actually give a petitioner satisfaction. They do keep records though. In fact, the local authorities have a vested interest in maintaining low petition numbers. Hence, the presence of “retrievers,” hired thugs who physically assault petitioners as they approach the petition office.

Throughout Petition it is crystal clear that the Chinese government has institutionalized corruption and hopelessly stacked the deck against the petitioners. Those victimized by unfair rulings have limited options locally for appeal (from the same corrupt bodies), so their only recourse is through the Kafkaesque “Petition Offices” in Beijing. Never in the film do we see the bureaucrats there actually give a petitioner satisfaction. They do keep records though. In fact, the local authorities have a vested interest in maintaining low petition numbers. Hence, the presence of “retrievers,” hired thugs who physically assault petitioners as they approach the petition office.

Petition is definitely produced in the fly-on-the-wall, naturalistic style of Jia Zhangke and his “d-generate” followers, but there is no shortage of visceral drama here. Each petitioner we meet has an even greater story of injustice to tell. Perversely, it seems it is those who do not take bribes who usually find themselves prosecuted in China. Petitioners are arrested, beaten, and even die under mysterious circumstances. Yet, it is through Zhao’s central figures, Qi and her daughter Juan, that we experience the emotional drain of the petitioning process with uncomfortable immediacy. Frankly, even if you have seen a number of Chinese documentaries, this film will still profoundly disturb you.

Zhao deserves credit for both his significant investment of time and his fearlessness. Not surprisingly, filming is strictly prohibited in the Petition Offices, but that did not stop him from trying, often getting more than a slight jostle for his trouble. Indeed, Petition represents truly independent filmmaking.

Petition is the cinematic equivalent of a smoking gun. It is impossible to maintain any Pollyannaish illusions of about the rule of law in China after watching the film. Yet, like Zhao, viewers will be struck by the petitioners’ indomitable drive for justice. May God protect them, because their government certainly won’t. A legitimately bold and honest film that needs to be seen, Petition opens this Friday (1/14) in New York at the Anthology Film Archives.

Posted on January 13th, 2011 at 10:18am.

3 thoughts on “Injustice in China: LFM Reviews Petition”

Comments are closed.