Watch the full episode. See more Irena Sendler: In the Name of Their Mothers.

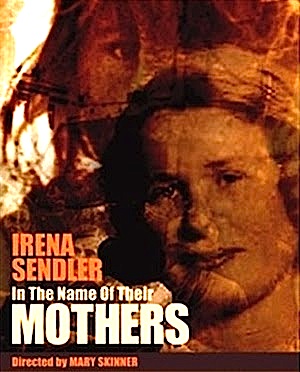

By Joe Bendel. There are more Polish citizens recognized by the State of Israel as Righteous among the Nations than any other nationality. Irena Sendler was not just one of the Polish rescuers. She was an underground ringleader. Yet it was not until long after the fall of Communism that the Catholic Sendler was widely hailed for her heroism. Featuring Sendler’s final interview of appreciable length, Mary Skinner’s documentary profile records her words and deeds for posterity in Irena Sendler: In the Name of Their Mothers, which airs on PBS stations across the country on Holocaust Remembrance Day, this Sunday.

Sendler was not the Irena whose story was told on Broadway in Irena’s Vow. That was Irena Gut. At tremendous personal risk, Gut sheltered twelve Jews slated for “deportation” in the basement of the home commandeered by an SS officer who had impressed her into service as his housekeeper. If not operating directly under the noses of the National Socialists, Sendler still faced profound dangers, eventually even seeing the inside of a Nazi prison and living to tell the tale.

Sendler was not the Irena whose story was told on Broadway in Irena’s Vow. That was Irena Gut. At tremendous personal risk, Gut sheltered twelve Jews slated for “deportation” in the basement of the home commandeered by an SS officer who had impressed her into service as his housekeeper. If not operating directly under the noses of the National Socialists, Sendler still faced profound dangers, eventually even seeing the inside of a Nazi prison and living to tell the tale.

Establishing a network of safe houses, Sendler and her colleagues in the resistance began smuggling children out of the ghetto and teaching them Catholic prayers should they ever be challenged by a German. Indeed, Poland’s widespread Catholicism was a major reason for the network’s success, with many Catholic schools and convents agreeing to shelter Sendler’s children. She even recruited a formerly virulent anti-Semite who simply could not countenance the atrocities underway. Ultimately, they saved over 2,500 children, including one man, now of late middle-aged years, who finally meets a crucial member of Sendler’s network in the film’s moving climax.

Skinner tells an amazing story with respect and economy. One gets a vivid sense of the fear permeating the era, gaining a genuine appreciation of Sendler and her comrades. However, the film never fully explains why Sendler and the veterans of the Polish resistance were largely scorned by the subsequent Communist regime. Of course, it makes intuitive sense that a record of resisting oppression was hardly the ticket to advancement in a Soviet captive nation.

Produced with great sensitivity, Mothers tells an important (but nearly overlooked) episode of history. Along with the recent 100 Voices, it should also help spread recognition of Poland’s record of resistance. It airs on many PBS outlets (check those listings) this Sunday (5/1).

—

Chicago-based jazz critic Howard Reich is an authority on Jelly Roll Morton. While it is often tricky winnowing the myths from the truth of the early jazz pianist’s life, Reich addressed a far more difficult research subject in his most recent book: his mother, Sonia. A Holocaust survivor, Sonia Reich’s late-onset Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) spurred her son’s investigation into her harrowing experiences during WWII, inspiring his book The First and Final Nightmare of Sonia Reich and Gordon Quinn’s subsequent documentary, Prisoner of her Past, which airs on many PBS stations nationwide over the next two days in recognition of Holocaust Remembrance Day.

One day, the eighty-some year old Reich suddenly fled her Skokie home in a deeply agitated state of paranoia. She was obviously delusional, but not suffering from Alzheimer’s or similar suspects. Indeed, she could recognize her grown children and grand children perfectly well. When her doctors finally diagnosed late PTSD (“with all the bells and whistles”), her son set out to discover its roots, hoping a secret from her past could untangle her knotted psyche.

Reich’s mother never talked about her past and her few surviving relatives are nearly as reticent. The only exception is her cousin, Leon Slominski, who was sheltered (both physically and emotionally) by a brave Czech family. Reich pointedly notes how the contrast between his survival through the compassion of others and his mother’s formative years of constant fear and flight profoundly shaped the people they are today.

As befits a film with a jazz critic as its central POV figure (and writer-co-producer), Prisoner employs the music in distinctive ways. Particularly effective is the use of Ornette Coleman’s “Lonely Woman” as the film’s theme. Poignant yet vaguely unsettling, it sets the appropriate mood, even for those who do not recognize the avant-garde innovator’s most “accessible” piece. (We also briefly hear guitarist Bobby Broom’s swinging soul jazz combo when Reich and Slominski visit Chicago’s Green Mill.)

In addition, Reich eventually visits the birthplace of jazz, New Orleans, as a way to take his story full circle. He shows how counselors are working with NOLA school children post-Katrina to prevent the sort of PTSD plaguing his mother. While these scenes seem somewhat abbreviated (and perhaps a bit tacked-on), it is nice to have some sort of positive take-away when the film ends.

As is often the case in real life, Prisoner does not end with a neat and discrete moment of closure. Yet, there are quite a few insights to be gleaned along the way. A very intelligent and compassionate film, it screens on many PBS outlets, including the Tri-State area, over the next two days (5/1-5/2). (Viewers might need to set their Tivos or old school VCRs in some markets, though). Definitely recommended, it also screens the traditional way this Tuesday (5/3) at the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles and the following Tuesday (5/10) in San Francisco at the Koret auditorium.

Posted on May 1st, 2011 at 10:23am.