[Editor’s Note: We want to wish everyone a Happy Easter & Passover. Below is a re-posting of LFM’s Blu-ray review of Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments (1956), from March 27th, 2011. Also: Turner Classic Movies is showing Easter- and Passover-themed films all day today. Check the TCM website for details.]

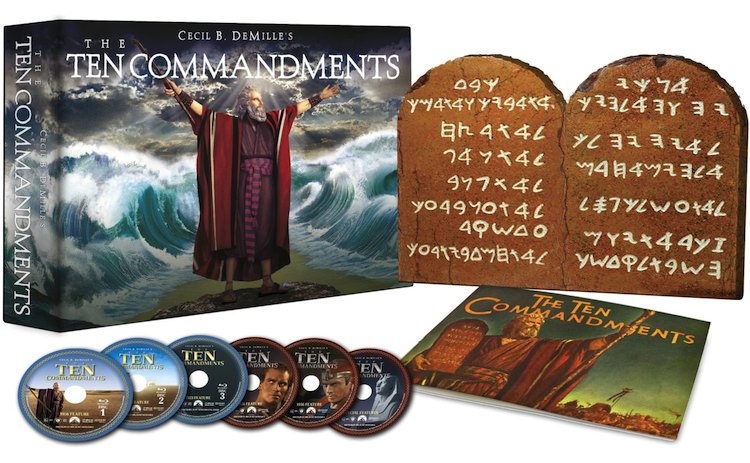

By Jason Apuzzo. The new Ten Commandments Blu-ray comes out this Tuesday, March 29th (see the trailer for the Blu-ray at the bottom of this post). Paramount will be releasing a 2-disc Blu-ray set of the classic film, and also a Limited Edition 6-disc DVD/Blu-ray Combo set, that features both Cecil B. DeMille’s 1956 and 1923 versions of the film – and a host of goodies, including a handsome archival booklet that may be worth the price of the set on its own.

The Ten Commandments is a special favorite of mine. Not only is the film one of Hollywood’s greatest epics of the 1950s, the film is also a timeless and enduring ode to human freedom – and one which seems to grow only more timely and urgent as the years go by. The Ten Commandments is a film that will always remain powerful and ‘relevant’ so long as there are souls yearning for freedom – even, as we’ve seen recently, in contemporary Egypt and North Africa where so much of The Ten Commandments was filmed.

We had the pleasure of showing what was then the best existing print of The Ten Commandments at our first Liberty Film Festival in 2004, when we invited cast member Lisa Mitchell to talk about her recollections of Mr. DeMille – and how influential he was in her life. Several years later Govindini and I spent time with Cecilia DeMille Presley, granddaughter of Cecil DeMille and a caretaker of his legacy – who shared some wonderful memories of her grandfather with us. Most special, however, was the opportunity Govindini and I had years ago to meet Charlton Heston himself at The Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood, when he introduced a special screening of The Ten Commandments. (We actually sat right behind him during the screening – and watched his reactions to the film, which he still seemed to take great delight in so many years later.) It was an extraordinary thrill to meet him; even late in life, he was still handsome and rugged, with a biting wit – but also a warm and generous spirit. He was the consummate gentleman.

The Ten Commandments is without a doubt one of the best films Hollywood has ever produced, and a carrier of important ideas about freedom, so I thought we’d take a little look back at it today. It also happens to be a magnificent showpiece for the Blu-ray medium – with the film’s rich, saturated colors, beautiful costumes and production design, endless desert vistas, and iconic visual effects sequences. To put it mildly, The Ten Commandments is not only an emotional spectacle of the heart … it’s also an eyeful.

Interestingly,The Ten Commandments happens to be the fifth highest-grossing film of all time, adjusted for inflation. When the film was released in 1956, theater tickets cost about 50 cents – and the film still grossed over $65 million. What this means is that at today’s ticket prices, The Ten Commandments would have grossed over $1 billion at the domestic box office. In the history of American moviemaking, only Gone With the Wind, Star Wars, The Sound of Music and E.T. have fared better at the box office than did DeMille’s extraordinary film.

I don’t mention The Ten Commandments‘ box office success because that denotes anything in particular about the film’s merits – success at the box office can always be misleading – but to suggest the kind of powerful bond this film has with the public. The Ten Commandments is, as it turns out, a beautifully written, directed, acted, photographed and scored film – a majestic and emotional voyage into one of the primary myths of Western religious life. It’s also the crowning achievement of one of America’s greatest moviemakers. At the same time, The Ten Commandments is something else: it’s a part of American popular mythology, as important to America’s filmic conversation about freedom and individual dignity as Casablanca, Gone With the Wind or On the Waterfront.

—

The Ten Commandments begins and ends, first all, with its legendary director – Cecil B. DeMille – who is possibly (along with D.W. Griffith, his contemporary) the first motion picture director anyone ever thought to call ‘legendary.’ The reason for this is not hard to find: DeMille’s personality was as vivid and outsized as his films, and that personality infused everything he did. DeMille’s father, mother and brother were playwrites and theatrical impresarios, and DeMille certainly seems to have had drama running through his veins – it seems inconceivable that the man could do anything dull or conventional.

DeMille intended The Ten Commandments to be the capstone of his career, which had begun back in 1914 with The Squaw Man. Ironically enough, DeMille had already directed a version of The Ten Commandments in 1923 (also included in the expanded Blu-ray set), although only about 55 minutes of that stylish silent epic were actually set in ancient Egypt – the rest being set in the America of the 1920s.

So what changed in the intervening years that made DeMille want to revisit this material? First, there was the success of DeMille’s own Samson and Delilah from 1949 – a film that kicked-off a run of Hollywood Biblical epics like Quo Vadis (1951) and The Robe (1953). Plus, DeMille was already comfortable with this sort of material, having directed landmark films like King of Kings (1927), The Sign of the Cross (1932) and my personal favorite from this period – Cleopatra (1934).

Technology was changing, as well. The 1950s brought large new cinema formats like Cinemascope, VistaVision and Cinerama that were perfectly suited to epic material. And this is truly an important point to emphasize: The Ten Commandments, filmed in VistaVision, is a huge, lavish film, shot in exotic Egyptian locales like Abu Rudeis, Abu Ruwash and Beni Youssef. If you ever find a more sumptuous looking film with more deeply saturated colors, or one that exploits widescreen, high definition film technology better, please tell me about it – because I haven’t seen it.

There were probably other reasons why DeMille was drawn to this material for his valedictory film statement. DeMille had been an ardent anti-communist for years, and he opens The Ten Commandments with an intriguing prologue in which he asks whether men are “property of the state … or are they free souls under God? Are men to be ruled by God’s law, or ruled by the whims of a dictator? This same battle continues throughout the world today.” One can almost imagine Dwight Eisenhower – or, much later, Pope John Paul II or President Reagan – uttering those some words at the height of the Cold War. It would be wonderful if our current President could utter them today.

The Ten Commandments was indeed made at the height of the Cold War, when our epochal conflict with the Soviet Union looked to be a long, twilight struggle. It’s not hard to believe that DeMille saw Pharaonic Egypt as emblematic of tyrannical dictatorships past and present, and the Jewish exodus as representative of a universal struggle for freedom – one that had taken on an even greater poignancy after the Holocaust.

Such political matters, however, never intrude on The Ten Commandments‘ robust, operatic storytelling. The Ten Commandments is a great film because its characters – primarily Moses (Charlton Heston), Rameses (Yul Brynner), and Nefretiri (Anne Baxter) – are all vibrant, complex and full of life.

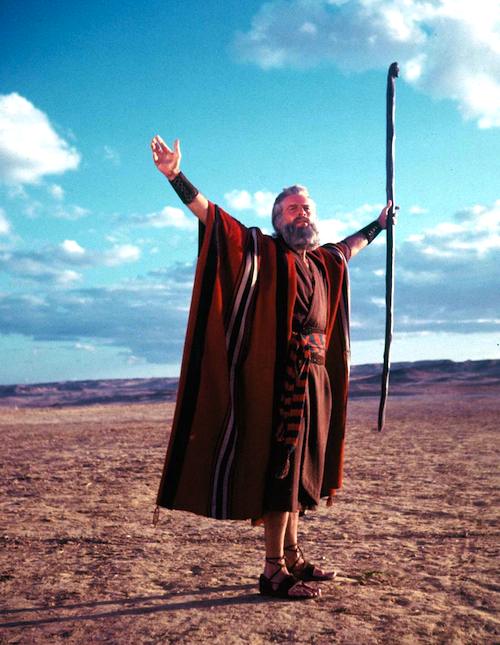

In the film’s opening act, Charlton Heston’s Moses – the orphaned son, unaware of his true identity – is a dutiful scion of Pharaoh’s court, who has earned his adoptive father’s love and respect through noble deeds, ironic wit and a gentle heart. Heston here is the classic good son, who’s played by the rules of the system and done everything asked of him thus far – and flawlessly. And yet … Moses also exhibits a generosity of spirit that puts him at odds with Egypt’s harsh overseers, such as the Master Builder – played with oily virtuosity by Vincent Price. So Moses doesn’t completely fit in with the world he currently dominates, and this will ultimately have consequences.

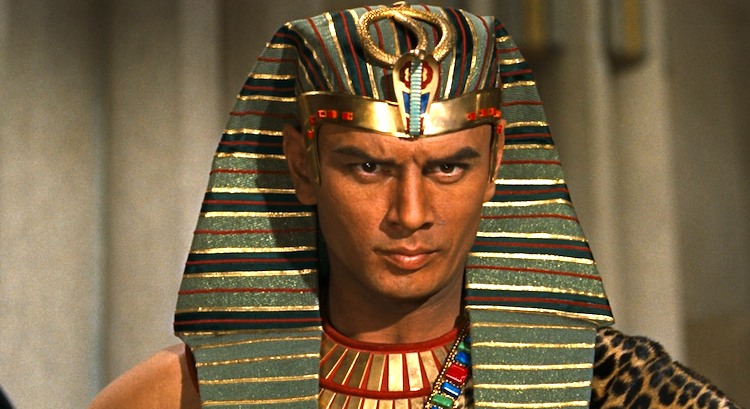

His half-brother Rameses, as played by the magnificent Yul Brynner, is a kind of arrogant, sexual panther, covetous of both the throne and the queen he believes are rightly his. Rameses is the most tragic figure of the film – but also the coolest. There’s nothing quite like watching Brynner intone, “So let it be written … so let it be done,” and then sweep away with his dark cape down down some endless palace hallway. Brynner’s Rameses here is like Darth Vader with sex appeal. Nonetheless, everyone despises him – including his queen-to-be, and his own father.

Anne Baxter’s delightful Queen Nefretiri is so full of love and sexual desire for Moses, she seems about to burst. She’s the paradigmatic woman ‘overdetermined’ by love, to the point that she can’t always see clearly. As full of warmth and desire as she is for Heston’s Moses, she doesn’t really understand him – and sees none of the major changes coming in his personality. Still, there are moments when her love seems so complete and all-encompassing that Moses appears a fool for leaving her.

The Ten Commandments is a long and intensely dramatic journey, over the course of which Moses’ character undergoes drastic changes. The first important change takes place when Moses learns of his Jewish heritage, something that leads him down an inevitable path toward exile – as his fellow Jews are enslaved by the Egyptian state. Everyone in Moses’ life wants to keep his heritage from him, even his Jewish mother (!), precisely because they know that as a man of integrity he won’t be willing to remain in the Egyptian court. This is an important point that DeMille makes here: Moses’ exile is not predetermined by his racial affiliation. He’s given every opportunity by Pharaoh, and by his family and loved ones, to remain in the court – even as a Jew. Nobody really wants him to go (except Rameses, his rival). His exile comes by choice, as a matter of conscience. Only he can make the decision to reject the Egyptian state and the tyranny it represents.

A word should be said here about Charlton Heston, who breathes nobility, humor and humanity into Moses. It’s commonly asserted that Marlon Brando was the top male performer in 1950s cinema – and, certainly, one would be hard-pressed to argue the point. Still, could the actor who so heroically embodied Moses and Ben-Hur (for which he received the Academy Award for Best Actor) in the same decade really be so far behind?

At a minimum, Heston’s ability to adapt himself to different historical periods was greater than Brando’s; yet, similar to Brando, Heston brought to his roles of this period a potent mixture of machismo and sensitivity, of violence laced with ironic humor – and also, most vitally, a nobility of spirit. All of these qualities are in evidence in The Ten Commandments, as Heston proves himself a magnetic and irresistible lead. In truth, it’s not hard to understand why so many women in the film are throwing themselves at him, even with Yul Brynner around. Heston, who specialized in the 1950s in playing rugged, individualist adventurers, is the very embodiment here of the self-reliant, independent man with a conscience. His performance in The Ten Commandments has the hard, iconic American quality of Marlon Brando’s in On the Waterfront or John Wayne’s in The Searchers – as a great individualist/non-conformist of the era.

Heston, of course, makes the decision to embrace his Jewish identity – with all of its consequences. So Pharaoh, as played with intelligence and warmth by Sir Cedric Hardwicke, reluctantly banishes him. Rameses, sadist that he is, carries out the banishment himself – letting Heston have a few final moments with Anne Baxter, and then sending him out into the harsh desert with only a day’s rations.

I actually think this is where the film hits its most interesting and dramatic points. Heston wanders into the desert, alone with the scorpions, hearing the echoes of voices from his past. You sense that his very sanity is at stake, as he reflects morosely on everything he’s given up. Yet he presses on, ever forward, his will power gradually being forged into steel. DeMille himself narrates these scenes, his stirring voice adding dramatic lustre to each moment. (DeMille himself was a highly popular radio personality at the time.)

Heston finally collapses at a small desert encampment – where, typically, he’s immediately surrounded by women. He eventually decides to settle down in the vicinity and live the quiet life with one of the women, a shepherdess named Sephora, played by the gorgeous Yvonne De Carlo. We should all be so lucky.

After a few years of keeping an eye on the sheep, Moses finally hears the call – the voice of God, emanating from the burning bush. Here he’s finally given his mission – to return to Egypt and liberate his people. I’ve always found it interesting that DeMille – apparently at Heston’s prodding – agreed to have Heston himself play the voice of God (Heston’s voice was slowed down, to give it more weight and resonance); DeMille and Heston seem to be emphasizing here that it’s very much Moses’ conscience, along with God, that is demanding his return.

Back in Egypt, incidentally, after the death of Pharaoh, poor Nefretiri is now stuck with Rameses – whom she despises. Rameses and Nefretiri here make the most delightfully miserable couple in movie history, possibly even surpassing Liz Taylor and Richard Burton in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Nefretiri, incidentally, still carries the torch for Moses – although she’s growing increasingly frustrated by his obstinacy. The man simply won’t give in!

Indeed throughout the film Moses’ high calling puts an enormous strain on his personal relationships. On returning to Egypt, from example, the previously gentle Moses becomes a driven man on a mission – a stern figure of fatherly discipline and moral admonition in moments when Israel’s faith weakens. As such, he’s no longer much of a lover, as he’s now becoming a revolutionary. He is slowly transforming from a man into a symbol – somewhat to the chagrin of his Jewish wife Sephora, and also his old Egyptian flame Nefretiri. DeMille is alive to these changes in Moses’ character, and much of the film is structured around the havoc Moses’ wanderings (both geographic and emotional) wreak on the women in his life – including both his natural and adoptive mothers. The quiet, intimate scenes featuring Moses’ many women are actually the best in the film, and belie the silly stereotyping of DeMille as someone who could ‘only do spectacle.’ DeMille never rushes these moments, or ignores the impact they have on the personal lives of the characters.

In the third act of the film, Moses is a sympathetic yet somewhat remote figure, always out of his loved-ones’ reach. He’s a driven man, probably burdened with too much responsibility. He becomes cranky – he can’t even be alone with God without arguing with Him. And one wonders at a certain point: is there a little bit of Cecil DeMille, too, in Moses? The DeMille who overflowed with warmth and loyalty to his friends, yet who transformed himself into a stern taskmaster on-set? DeMille the visionary, who exiled himself from the sophisticated world of New York theater to the desert of southern California – all to found a new entertainment industry? The Ten Commandments may be a more personal film than we might previously have thought. I suspect DeMille himself wrestled with God, with loneliness – and with lovely, tempestuous women – in much the same way Moses does in this film.

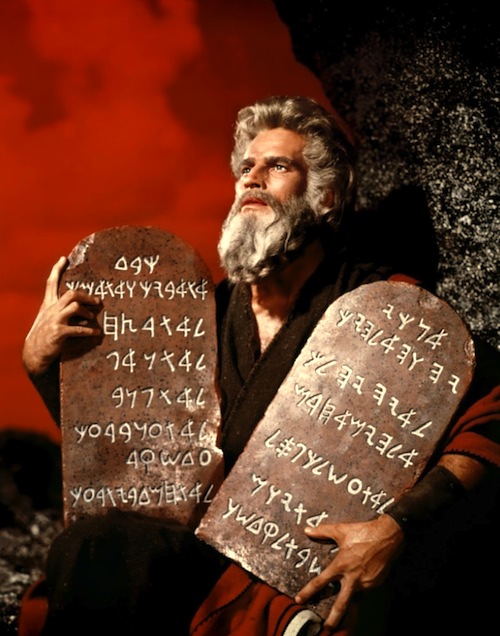

The movie builds to the justly famous moment at which Moses parts the Red Sea, one of the iconic scenes in film history. In this cataclysmic sequence, the Jewish slaves escape Pharaoh between towering walls of water, after which Pharaoh’s pursuing army is crushed under enormous waves. It’s difficult to imagine how today’s digital effects would improve this sequence, or give it any more emotional impact than it already has. In fact, it’s possible that the movie should’ve ended there – except that DeMille still has a dazzling sequence up his sleeve, in which he intercuts a massive pagan orgy with God’s burning of the 10 Commandments into stone atop Mount Sinai. Elmer Bernstein’s musical score during this sequence is really extraordinary, as is the intercutting between the orgy below and the supernal fire above.

The film ends, of course, with Moses finally ‘retiring’ from the scene just before his people make it to the Promised Land. It’s a poignant conclusion to an epic, 3 hour and 40 minute journey unlike any other.

I’m very glad Paramount wasted no further time in digitally restoring The Ten Commandments and releasing such a lavish Blu-ray set. DeMille’s film certainly deserves it, and hopefully The Ten Commandments can now reach a wide new audience. The Ten Commandments represents American filmmaking on a heroic scale, as it deals with big emotions and big ideas.

The The Commandments is very much about what America meant to Cecil DeMille: freedom. Although the film was likely intended as a parable of the Cold War era, its message is timeless. The film reminds us today, at a time when we apparently need such reminding, that we’re only a just and righteous society when we value human freedom and commit ourselves fully to its cause. Indeed, The Ten Commandments concludes with these precise words:

“Go, proclaim liberty throughout all the land, and to all the inhabitants thereof.”

I can think of no better message for our times.

Posted on April 8th, 2012 at 3:20pm.

One thought on “For Easter & Passover: A Review of The Ten Commandments on Blu-ray”

Comments are closed.