By David Ross. Lyonel Feininger has suddenly and splendidly swung into view, like some rare astral event. The Whitney Museum is holding, through October 16, an exhibition called “Lyonel Feininger: At the Edge of the World,” which should go far toward confirming the obvious: Feininger was for half a century one of the world’s chief painters. The exhibition is a major contention on his behalf, as the magnificent exhibition catalogue – available here – makes clear.

Feininger (1871-1956) is less celebrated than he should be principally because he confuses the national categories that structure so much art history. He was born in New York to German parents. So far so good. At age sixteen, he shifted his studies to Germany and wound up becoming the proverbial American abroad. During his fifty-year German sojourn, he fell in with the expressionists and later joined the faculty of the Bauhaus as an instructor in printmaking. During the 1920s, he became one of the “Blue Four,” an eminent coterie that included Kandinsky, Klee, and Alexej von Jawlensky (see here for an excellent survey). Feininger returned to the U.S. in 1937, after the Nazis sent a not so subtle signal by including his work in their infamous “Degenerate Art Exhibit.”

Neither quite American nor quite German, Feininger figures in nobody’s national tale. Had he remained in the U.S. or expatriated himself in England or France – countries entwined in our own modernist myth – I suspect he would now be considered one of the Titans of twentieth-century American art. Certainly he was a greater painter than Marsden Hartley (born 1877), Georgia O’Keeffe (born 1887), and Thomas Hart Benton (born 1889), who may be his closest American counterparts. As it is, the Wikipedia entry on American art does not even mention Feininger.

Complicating matters further, Feininger passed through three distinct and not easily reconciled phases. He was first a German expressionist, an oil cartoonist of spooky elongations and lurid Halloween scenery; he was second an impeccably elegant cubist of the school of Cezanne in its Weimar manifestation; he was third – especially during his later American years – a sketch artist whose modest drawings of sailboats, waterfront scenes, and New York buildings translated nature into a kind of wiry architecture, a taut cross-hatching whose inspiration, it’s not incredible to think, may have been the rigging of ships. These latter drawings, sometimes overlaid with watercolor, have a wonderful simplicity, a relaxed confidence in the soundness of their own geometry. Which is the primary Feininger? What explains the strange, disjunctive pattern of his career? There are no clear answers and thus few critics inclined to take up the questions.

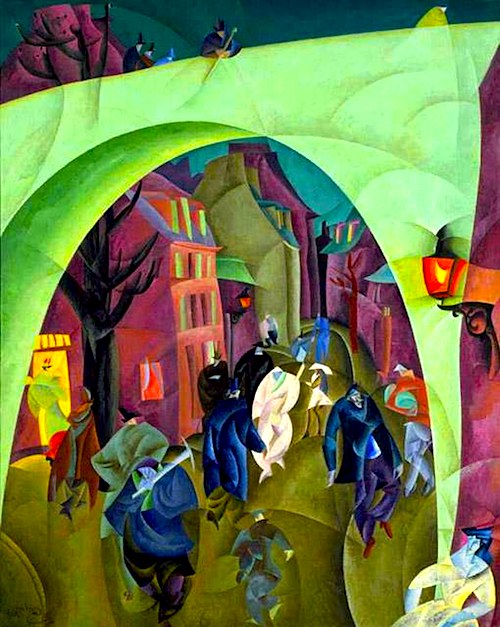

Feininger’s “Green Bridge II” (1916), a creepy still from some colorized Murnau film of the mind, exemplifies Feininger’s expressionist phase. This thrilling painting hales from the North Carolina Museum of Art, my neighborhood museum, so to speak. On her first museum outing, my five-year-old daughter spotted the painting and announced to everybody within a twenty-foot radius, “Look! It’s Diagon Alley!” Ever since, the association has been inescapable.

At his very best, during the refulgent cubist phase of the 1920s, Feininger was a poet of prismatic form and color, a kind of jeweler creating lapidary, multi-faceted gems of light and view, drawing on cubism without succumbing to its sometimes inhumane abstraction and the merely provocative derangement of normal geometry. His great oil paintings of the 1920s – Baltic seascapes, northern churches, bird-winged sailboats – are essentially lyric. They are among modernism’s closest approaches to a fully satisfactory marriage of radical form and melodic adoration of the world in its serene and elegant beauty. Certain paintings – like Bird Cloud (1926) in the Busch-Reisinger Museum at Harvard, Church of the Minorites II (1926) in the Walker Art Center, and Dune and Breakwaters (1939) in a private collection – are simply among the most gorgeous works of the twentieth century.

Posted on September 13th, 2011 at 10:50am.

I like this period of modern art, just prior to the entire enterprise running off the rails into the post modernist trash pile. It would be nice to see some retro work along these lines.