By David Ross. I make my living stumping for high modernism, so I am not exactly an enemy of the avant-garde and the experimental, and yet I am diffident about the extraordinary reputation of Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988), the Brooklyn-born Haitian-American wunderkind who during the early eighties vaulted from graffiti artist to Warhol protégé and Madonna boy-toy in a mere ten years before dying of a heroin overdose.

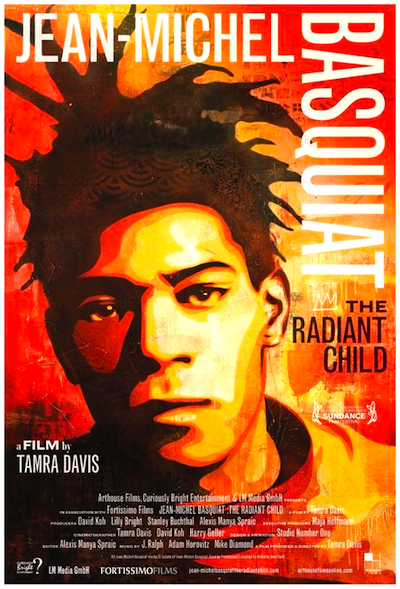

I turned to Tamra Davis’ documentary Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Radiant Child (2009) for a glimmer of an explanation. The documentary turned out to be a trove of vintage footage and articulate commentary provided by those who stood just at the perimeter of Basquiat’s spotlight, but in the end I could find no trail of breadcrumbs to lead me out of the postmodern funhouse in which fame multiplies by some hidden law of light and reflection and desire. Basquiat wrote meaningless koans with spray paint and became famous; he founded a band with some downtown types, none of whom could play instruments, and become even more famous; he mooned around the trendiest clubs and become more famous still. He painted childlike hieroglyphics on whatever he could find and became a superstar. Dying young, he became a legend, which is precisely what he had set out to be.

Really, though, what is the substance of his achievement? His art is certainly vivid and energetic, and its neo-expressionist assault on the minimalism and conceptualism of the seventies is impossible not to cheer (“white paintings, white people, white wine” is how one interviewee recalls the pre-Basquiat era). And yet his art does not – for me at least – resolve into meaning. Its presumptive symbol language is too private and haphazard, and it is not tantalizing enough on its face to rouse my analytic energy and resolve. We kill ourselves to make sense of Finnegans Wake because we intuit that there is sense to be made; Basquiat’s art demands a gamble of time and energy that seems to run against the odds of an ultimate payoff.

Really, though, what is the substance of his achievement? His art is certainly vivid and energetic, and its neo-expressionist assault on the minimalism and conceptualism of the seventies is impossible not to cheer (“white paintings, white people, white wine” is how one interviewee recalls the pre-Basquiat era). And yet his art does not – for me at least – resolve into meaning. Its presumptive symbol language is too private and haphazard, and it is not tantalizing enough on its face to rouse my analytic energy and resolve. We kill ourselves to make sense of Finnegans Wake because we intuit that there is sense to be made; Basquiat’s art demands a gamble of time and energy that seems to run against the odds of an ultimate payoff.

The film’s numerous interviewees note Basquiat’s influences: Charlie Parker, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, William Burroughs, Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning. There’s something to be said for each of these connections, but Basquiat’s art seems to me closest to that of De Kooning: stark, nightmarish, garishly and luridly childlike, suffocating in its self-enclosed logic. I would say, though, that De Kooning’s punch is more concerted and harder thrown, his vision more ordered and hefty. Basquiat may have been more talented – I have no idea – but I doubt he had reflected nearly as carefully about what he was up to or exercised the same kind of winnowing intelligence. He seems to have worked by spontaneous trial and error, adding, subtracting, and overlaying in accordance with some inner sense of arrangement and meaning. This kind of improvisation can be electrifying when executed with supreme technical command (Keats, Coltrane, Pollock) but Basquiat was very far from virtuosic.

I can comprehend Basquiat only as a talented and perhaps semi-inspired cipher whose most superficial accouterments – name, hair, race – won him the role that had to be filled one way or another: that of the boy genius, the tragic naïf, with royalties and two-hundred years compounded interest owed to Keats. Basquiat was particularly suited to this role, being soft-spoken, dreamy, and vague in a way that might be misinterpreted as poetic. In comparison to Patti Smith, perhaps the only genuine genius of the punk-era downtown scene, Basquiat seems flimsy; his flourishes may or may not dazzle, but they are never more than flourishes.

The film, incidentally, adopts as epigraph Langston Hughes’ bad poem “Genius Child”:

This is a song for the genius child.

Sing it softly, for the song is wild.

Sing it softly as ever you can –

Lest the song get out of hand.

Nobody loves a genius child.

Can you love an eagle,

Tame or wild?

Can you love an eagle,

Wild or tame?

Can you love a monster

Of frightening name?

Nobody loves a genius child.

Kill him – and let his soul run wild.

The suggestion that the world “kills” the “genius child” in a snit of aggressive philistinism or atavism is ludicrous and particularly ludicrous in this case. Everybody loves a “genius child” and certainly everybody loved Basquiat. He was surrounded by benefactors. They paid his rent, slept with him, bought him paints, canvases, whatever he needed, furnished him with studio space, collected his paintings from the very start. Basquiat, in his early twenties, was fast on his way to substantial wealth and permanent celebrity. Had Basquiat lived only a few more years he would have been showered with a MacArthur Genius Grant and other remunerative goodies, and he would have wound up splitting his time between a downtown duplex and the south of France, with occasional appearances on Oprah to pontificate on the strain of being a genius.

Has society ever genuinely killed a “genius child”? It’s very hard to think of a case. Shelley initiated the accusation in “Adonais,” his bloated elegy for Keats, alleging that John Wilson Crocker’s savage review of Endymion in the Quarterly Review had done in the young poet. He writes in his preface:

The savage criticism produced the most violent effect on his susceptible mind; the agitation thus originated ended in the rupture of a blood-vessel in the lungs; a rapid consumption ensued, and the succeeding acknowledgements from more candid critics of the true greatness of his powers, were ineffectual to heal the wound thus wontonly inflicted.

Hating this kind of misty whining, Byron did his best to stab the trope in its cradle. His wry retort comes in Don Juan (Stanza 60, Canto XI):

John Keats, who was killed off by one critique,

Just as he really promised something great,

If not intelligible, without Greek

Contrived to talk about the Gods of late,

Much as they might have been supposed to speak.

Poor fellow! His was an untoward fate:

‘Tis strange the mind, that very fiery particle,

Should let itself be snuffed out by an Article.

Byron did his best, but it was no use. Every suicidal, immuno-compromised, coke-snorting, sport-car-gunning boy-genius would be laid like some pierced fawn on society”s doorstep.

The only figure who begins to make sense of Hughes’ silly poem is Oscar Wilde, though his genius was only part of the problem. Wilde was genuinely destroyed; all of the others – from Shelley himself to Michael Jackson – destroyed themselves for reasons of their own.

Posted on December 14th, 2010 at 9:45am.

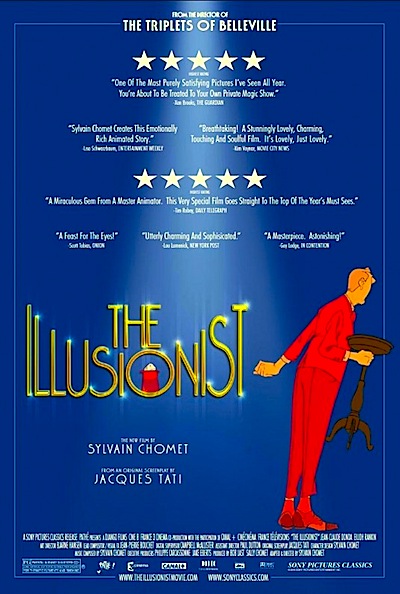

As the film begins, the perhaps once-great Tatischeff (Tati’s pre-showbiz name) schleps his mean-spirited rabbit and assorted magical gear to and from dilapidated theaters and middling private gigs. In a pleasant surprise, one of his best bookings turns out to be a small pub far up in the Scottish Highlands. The locals are all friendly in their strange Gaelic way and appreciate the show well enough. Alice, a shy young maid in his public house, is particularly fascinated by the Illusionist and his illusions. Something about her touches him, as well, inspiring an act of kindness on his part. So when she invites herself along with the Illusionist, he begins to act as a kind of surrogate father.

As the film begins, the perhaps once-great Tatischeff (Tati’s pre-showbiz name) schleps his mean-spirited rabbit and assorted magical gear to and from dilapidated theaters and middling private gigs. In a pleasant surprise, one of his best bookings turns out to be a small pub far up in the Scottish Highlands. The locals are all friendly in their strange Gaelic way and appreciate the show well enough. Alice, a shy young maid in his public house, is particularly fascinated by the Illusionist and his illusions. Something about her touches him, as well, inspiring an act of kindness on his part. So when she invites herself along with the Illusionist, he begins to act as a kind of surrogate father.