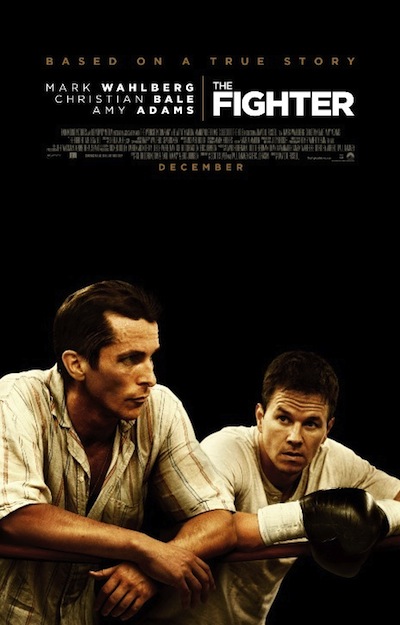

By Patricia Ducey. The Fighter opens with two brothers mugging their way through the streets of their working class neighborhood against the defiant wail of “How You Like Me Now,” and I’m hooked. I grew up in an Irish neighborhood, and I know this place. We had the fight in us too.

Director David O. Russell pays homage to all that life-affirming fight in his raucous, memorable The Fighter, the story of how one man comes into his own against all the odds, great and small. “Irish” Micky Ward (Mark Wahlberg) lives in the shadow of half brother Dick Eklund (Christian Bale), once a champion boxer, now a crackhead and neighborhood goof. Micky, an up and coming fighter himself, trains with Dick, still an able coach (when he shows up), while mother Alice (Melissa Leo) manages his budding career along with Dickey’s “comeback.” Not surprisingly, the chaos of his dope-addled brother, grasping mother and passel of sisters drowns out Micky’s own aspirations.

The movie opens as Dickey, partying at the crackhouse, almost misses the flight to one of Micky’s out-of-town bouts. Micky and his mother drag him to safety, again. Alice treads lightly on his drug problem, however, hoping he will just get over it–an HBO crew is filming a documentary on Dickey’s comeback and she doesn’t want to jinx it. She also needs Micky’s career to save Dickey; and, for now, dependable, stalwart Micky accepts his role as actor on Dickey’s stage.

The movie opens as Dickey, partying at the crackhouse, almost misses the flight to one of Micky’s out-of-town bouts. Micky and his mother drag him to safety, again. Alice treads lightly on his drug problem, however, hoping he will just get over it–an HBO crew is filming a documentary on Dickey’s comeback and she doesn’t want to jinx it. She also needs Micky’s career to save Dickey; and, for now, dependable, stalwart Micky accepts his role as actor on Dickey’s stage.

But then he falls for sexy redhead bartender Charlene (Amy Adams), and she eventually for him. After he takes a bad beating in a mismatched bout his mother and brother set up, she is the one to voice what he cannot: he has to stop allowing his family to wreck his life. When Micky and Charlene take the first steps away from the family, this sparks the conflict that forms the rest of the film. Gone is the “ticket out of poverty” meme and the class struggle meme. It’s not about race either, as Russell notes with humor: as Dickey negotiates an alliance with a Cambodian clan in some petty criminal enterprise, the Cambodian spokesman accuses him of cheating him because of race. “No, no,” Dickey’s associate assures him, “We don’t hate Cambodians. White people do this to other white people all the time.”

Mickey is simply a man who must put his own life in order. He has to be willing to fight for his independence from anything that will drag him down – even a beloved brother. He is not a victim of drug abuse or of political oppression or the church or the mob or anything else outside of his own self-doubts. His family uses him because he lets them. Micky has to earn his freedom himself—and this is a deeply conservative, even ‘objectivist,’ narrative. Russell and his actors keep that idea at the forefront with ruthless precision.

The Fighter, as a boxing movie, is refreshingly absent the sentimentality of Rocky or the chilly artiness of Raging Bull. Micky and his brother simply love their sport, and are good at it. They have the physical strength to overpower and the mental acuity to out-strategize their opponents. Boxing is their work, and Russell thus limits the boxing scenes to two pivotal fights and does not fetishize the physical spectacle. As an aside: boxing, in my mind, does not glorify violence so much as the sense of fair play and courage that help restrain violence. Yes, boxing (like all sport) is ritualized mayhem, but it’s a celebration of a process that marks civilization’s triumph, however temporary, over our animal natures.

Russell also comments on a predatory media’s exploitation of people outside the intellectual space of the upper classes. He frames the story with an HBO crew filming a documentary about Dickey. The family think it’s about a fighting comeback, but that’s subterfuge. Eventually they see, to their horror, that it’s a cautionary fable about another lower class guy’s fall from grace into addiction. It “fits the narrative,” and Russell rightly mocks the media’s condescension.

The cast excels. Christian Bale transforms himself (without going overboard) into the part as big brother, part-crackhead Dickey, and a bleach-blond Melissa Leo terrifies us with her tiger mother Alice. At first, next to these two wild and voluble characters, Mark Wahlberg’s performance may appear muted, but suddenly we realize we can’t take our eyes off him. That’s how he catches and holds our attention—by whispering, by making us come to him. His small smile, for instance, when he finally convinces Charlene to give him her number, lights up the room.

But the script by 8 Mile’s Scott Silver (and three other WGA-credited writers) and director Russell’s work gave them the goods. Russell has said he wants to grab you by the throat and heart at the beginning of this movie, and he accomplishes his mission.

We recognize Micky’s conflict; we know it and feel it in our gut because it is so essentially human. We are almost afraid to root for him, let alone his brawling kin, but we watch and hope still. Filled with humor and pathos and a winning cast, The Fighter’s “message,” if there is one, is: stay off the ropes, get in the fight.

Posted on January 24th, 2011 at 11:56am.