By Joe Bendel. As usual, Isaac Asimov got it right. In the future, robots follow his three laws. However, there are still a lot of grey areas for androids, including the very nature of their existence. Two high school students grapple with the notion of human-android relations in Yasuhiro Yoshiura’s Time of Eve, a surprisingly smart science fiction anime feature adapted from his webseries, which screens during the 2011 New York International Children’s Film Festival. Continue reading LFM Review: Time of Eve @ The New York International Children’s Film Festival

Category: Trailers

What a Revolution Should Look Like: The Power of the Powerless

By Joe Bendel. Initially, the student-driven revolution against Czechoslovakia’s hardline Communist government seemed hopelessly naïve. In a mere eleven days, the humbled regime relinquished their dubious claim to power, clearing the way for democratic elections. Unlike the current Middle Eastern “Days of Rage,” it all transpired without demonstrators committing any sexually, ethnically, or religiously motivated acts of violence. In fact, whether Havel and the Velvet Revolution were too forgiving of their former oppressors is one of the questions raised in Cory Taylor’s documentary, The Power of the Powerless, which opens this Friday in the Los Angeles area. Continue reading What a Revolution Should Look Like: The Power of the Powerless

Jafar Panahi (Not) at The Asia Society: The Circle

By Joe Bendel. It is good to be a man in Iran, provided you do not care about religious, political, or economic liberty. However, women must endure a profoundly misogynistic and frequently brutal society that regards them as little more than the chattel of men. Jafar Panahi confronted the unjustness of Iran’s treatment of women directly in The Circle, the winner of the 2000 Venice Film Festival’s Golden Lion prize – and a film which was promptly banned in Iran. Not content to stop there, the Iranian government has recently barred Panahi from further filmmaking for the next twenty years and sentenced him to six years in prison. Indeed, Panahi’s circumstances only heighten the poignancy of The Circle, which screens this Friday as the concluding film of the Asia Society’s retrospective-tribute to the persecuted filmmaker.

Solmaz Gholami (remember that name) has just given birth to a healthy baby girl. This should be happy news, but her mother is distraught. The in-laws were expecting a boy and will surely abandon their daughter-in-law and grand-daughter. The obvious high school science fact that it was the husband who failed to supply the Y chromosome is lost on such medieval fundamentalists. As Gholami’s mother seeks help from her family, Circle peels off, focusing on its next set of characters.

Three women have just been released from prison on unspecified “morals” charges. However, the Iranian system sets them up in a perverse Catch-22, kicking them loose without the necessary identification papers should they be stopped once again by the police (who are definitely out hunting for women in their situation). Lacking a male chaperone, sweet-tempered Nargess cannot take the bus trip back to her provincial home. Despondent, she seeks another friend, Pari, an escapee with even greater problems. She is four months pregnant with the child of her executed lover. From Pari, the chain continues, introducing a desperate mother and a woman arrested as a prostitute (perhaps not without some justification in her case), who ultimately brings the story to its symmetrical conclusion.

Sexism is a wholly insufficient term for the abuses Circle dramatizes. A stinging indictment – but also an honest, frequently moving human drama – it is not hard to see how it ran afoul of the state censors. Yet the film is not just a testament to Panahi’s artistic integrity. The cast deserves tremendous credit, especially those playing fallen women while living under a literal-minded fundamentalist theocracy. Though Circle is the only credit listed on IMDB for many of the actresses, their work has a powerful immediacy. They are frighteningly believable. Perhaps most haunting is Nargess Mamizadeh as her namesake. Young and innocent, to paraphrase the tagline of one of Circle’s international posters, she could only be guilty of being a woman.

To be banned by the mullahs might be a greater accolade than the raft of awards Circle won on the international festival circuit. Of course, the repercussions for Panahi have been severe. A truly bold film, Circle has only appreciated in importance and relevance with the regime’s campaign against the filmmaker. Highly recommended, it screens this Friday (3/11) at the Asia Society—and once again, tickets are free.

Posted on March 7th, 2011 at 10:01am.

LFM Review: Cannes Palme D’Or Winner Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives

By Joe Bendel. An old commie hunter, Uncle Boonmee is haunted by spirits. However, his ghosts are largely benevolent, seeking to comfort Boonmee during his final days. Rife with magical realism but deliberately toying with narrative structure, Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Cannes Palme D’Or winning Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives is now playing in New York at Film Forum and elsewhere around the country in a limited art house release.

Boonmee is slowly dying from a humiliating kidney dysfunction. He is faithfully attended by his Laotian servant Jai and the ghost of his deceased wife Huay, among others. Even his long lost son Boonsong pays his final respects, despite having transformed into a red glowing-eyed monkey spirit, lurking the dark heart of the jungle with his beastly cohorts.

It has been an eventful life, but it is nothing compared to Boonmee’s visions of his previous incarnations, particularly an episode in which a mystical catfish ravishes a self-esteem-challenged princess. Consistently obscure throughout Recall, Weerasethakul never explicitly spells out Boonmee’s role in this Leda-like tale, but since the lagoon is described as the place where Boonmee’s lives began, it seems safe to assume there is some fishy DNA in his karma.

Though Boonmee ruefully suggests his current bad karma stems from his past anti-Communist military activities, perhaps he should ask the Cambodians about what he helped spare his countrymen (“you did it for your country,” his sister-in-law Jen reminds him). Regardless, Weerasethakul’s somewhat veiled commentary is so deeply buried under multiple layers of symbolic meanings and narrative gamesmanship, it is doubtful Recall will inspire many viewers to spontaneously erupt in a rendition of “The Internationale.” Instead, those so inclined will probably break the film down into the parts they can deal with, whether that might be the animatronic catfish or Buddhist reincarnation themes.

Of course, there is something problematic about a film’s whole, if it is less than its constituent parts. Between its double-secret allegories, nonlinear forms, and deliberate stylistic shifts, Recall is so busy displaying a self-conscious artiness, the rain forest gets lost for the trees. In fact, Recall along with the experimental companion short Letter to Uncle Boonmee were conceived as part of Weerasethakul’s multi-media, multi-platform project Primitive. Indeed, there are times when the static nature of Recall and particularly the narrative-free Letter seem more closely akin to installation videos than stand-alone films.

Though the late reappearance of characters from Weerasethakul’s past films might be enriching for those in the know, bringing things full circle, it further limits the film’s ability to connect with average well-meaning audiences. Still, Thanapat Saisaymar manages to express something fundamentally and universally human as the dying Boonmee, while Jenjira Pongpas also adds a bit of grace to the proceedings as Jen.

Obviously, Recall is a film for hardcore art-house and festival audiences. It boasts some reasonably nice performances, but it thoroughly confuses the distinction between avant-garde provocation and portentous pretention. A film that does not live up to its festival acclaim, Recall is now playing in New York at Film Forum and elsewhere in limited release.

Posted on March 4th, 2011 at 1:42pm.

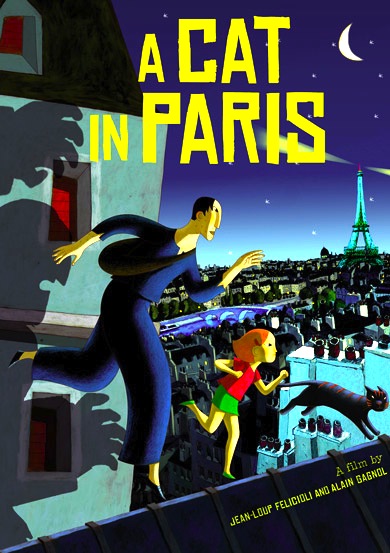

LFM Review: A Cat in Paris at The NYICFF 2011

By Joe Bendel. Paris is a playground for an adventurous cat like Dino. By day, he is the loyal tabby of the police superintendent’s daughter. By night, he joins the nocturnal adventures of an actual cat burglar, climbing the city’s ornate masonry and gothic gargoyles. The City of Lights rarely looked as beautiful on the big screen as it does in Alain Gagnol and Jean-Loup Feliciolli’s animated feature A Cat in Paris (trailer here), which has its American premiere at The 2011 New York International Children’s Film Festival.

Young Zoe has not spoken a word since her father was murdered by gangster Victor Costa. Her copper mother is too busy working the case to help her adequately work through her grief. She spends most her time with Dino, who enjoys bringing her little presents, like small dead animals and the occasional diamond bracelet. One night Zoe follows on Dino as he slinks off to join the Rafflesesque Nico, only to stumble across the Costa gang. The chase is on, across the stylishly rendered Parisian cityscape.

Young Zoe has not spoken a word since her father was murdered by gangster Victor Costa. Her copper mother is too busy working the case to help her adequately work through her grief. She spends most her time with Dino, who enjoys bringing her little presents, like small dead animals and the occasional diamond bracelet. One night Zoe follows on Dino as he slinks off to join the Rafflesesque Nico, only to stumble across the Costa gang. The chase is on, across the stylishly rendered Parisian cityscape.

The hand-drawn Cat is a wonderful antidote for the mass-produced computer animation constantly dumped into multiplexes. These figures have an idiosyncratic look that deliberately evokes a sophisticated Parisian sensibility. If Toulouse Lautrec was resurrected to craft an animated film, he would probably look up Gagnol and Feliciolli.

Indeed, the city is an integral part of film, right down to its fitting conclusion at Notre Dame. Though clearly produced with young viewers in mind, the romantic urban backdrops, the hat-tips to film noir, and the jazz-influenced soundtrack (including a vintage Billie Holiday rendition of “I Wished on the Moon”) will keep parents and other ostensive adults quite engaged. A well constructed feature, Gagnol and Feliciolli maintain a brisk pace, while showing the action from dramatic angles that further heightens the noir appeal.

Cat is a thoroughly charming film with genuine heart and just enough attitude to avoid cloyingness. Though admittedly brief at sixty-five minutes, it packs a lot into that time, including some very cool closing credits. NYICFF and gKids have a good eye for animated features, having previously selected intelligent and artfully crafted features like Sita Sings the Blues and In the Attic for previous festivals. The tradition continues this year with Cat and some first-rate anime imports. Highly recommended, Cat screens at NYICFF on March 5th, 6th, 12th, 13th, and 19th, but it appears tickets are only still available for Saturday the 12th, so act fast.

Posted on March 2nd, 2011 at 10:42am.

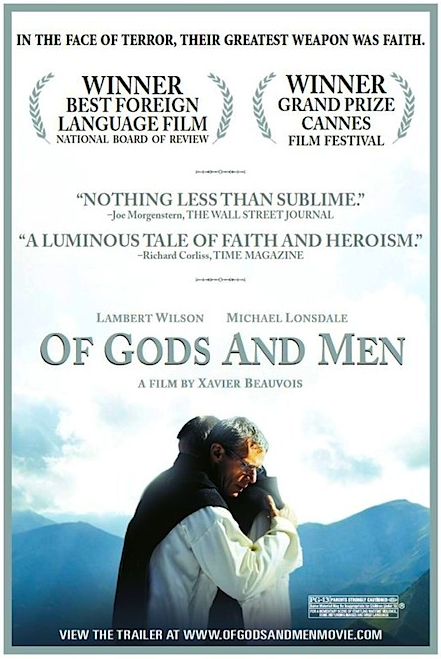

Faith in the Face of Islamist Violence: Cannes Grand Prize Winner Of Gods and Men

By Joe Bendel. They lived in perfect harmony with their Muslim neighbors. Their mission was one of charity, conducted with tolerance, yet seven of their ranks were executed in 1996, either by Islamist guerillas (who claimed responsibility) or the Algerian army in an attempt to cover up a botched rescue attempt—opinions vary. Though a small group of French Trappist monks knew they were in harm’s way, they went about their final days just as they always had. Xavier Beauvois captures their faith and fellowship with genuine sensitivity while trying to finesse the worldly hatreds that ensnared them in his thinly fictionalized Of Gods and Men, the 2010 Cannes Grand Prix winner, which opens in New York and Los Angeles today.

They do not reside in seclusion, but are actively engaged in their adopted community. The eight Trappists of Tibhirine do many good works, yet their daily existence is still comparatively quiet and meditative, filled with prayer and liturgical singing. Brother Luc runs the free clinic and distributes clothes to the needy. Brother Christian is a learned scholar of Islamic theology. Brother Christophe struggles with his faith, yet their provincial corner of Algeria is the only place he feels a sense of belonging.

They do not reside in seclusion, but are actively engaged in their adopted community. The eight Trappists of Tibhirine do many good works, yet their daily existence is still comparatively quiet and meditative, filled with prayer and liturgical singing. Brother Luc runs the free clinic and distributes clothes to the needy. Brother Christian is a learned scholar of Islamic theology. Brother Christophe struggles with his faith, yet their provincial corner of Algeria is the only place he feels a sense of belonging.

Unfortunately, the world around them is far from peaceful. As French Christians, they are prime targets for the Armed Islamic Group of Algeria. Fearing their presence will attract trouble, the Algerian government wants them to evacuate. However, many of their neighbors want them to stay, believing only the monks’ presence has protected them from the atrocities reported throughout the countryside. The dilemma for the monks is obvious: what course of action is most consistent with their mission and the tenets of their faith?

Working closely with monastic advisor Henry Quinson and choirmaster François Polgar, Beauvois renders their not-so cloistered life with respect and scrupulous attention to accuracy. The issues of faith the monks grapple with are serious, not just because of their obvious life-and-death implications. Indeed, Beauvois and co-screenwriter Etienne Comar offer the most insightful and compelling depiction of Christian monasticism seen on-screen since Into Great Silence, a film Men somewhat resembles in tone – despite the former being a documentary about Carthusians.

As befitting men of God, the monks forgive their captors (and likely executioners). It is their final act of Christian charity, explicitly elucidated in the concluding narration of Brother Christian’s journal. However, Beauvois’ constant pleas to distinguish Islam from Islamists run the risk of protesting too much. Frankly, he somewhat undercuts the feelings of humanist empathy and solidarity inspired by his graceful portrayal of the Trappists by fetishizing their murder as an act of martyrdom on behalf of their Muslim murderers. As not just men of the cloth, but as those trespassed against, it is their place and perhaps their highest calling to forgive. That right is not ours to exercise.

Despite the agenda ultimately appended to Men, it is a finely crafted film. Caroline Champetier’s warm lens finds the weathered beauty in the Algerian land and its people. Beauvois’ use of both silence and Polgar’s arresting chorale music is equally adept. Yet, it is the dignity and intelligence the cast invests in the monks that are redemptive above and beyond any pat message tacked onto their tragic story. Truly, the eight principles give career performances, but veteran French character actor Michael Lonsdale is a genuine standout as Brother Luc – while Lambert Wilson effectively centers the film as wise Brother Christian.

These are men, albeit of God, but men none-the-less, rather than symbols. The greatest aspect of Men is its success in delineating the monks as characters and conveying the distinct ways Christian faith manifests itself through their callings. Though it requires time to contemplate and digest, in the final analysis Men is a quietly moving film of considerable substance. It opens today (2/25) in New York at the Landmark Sunshine and next week in Los Angeles at Laemmle’s Playhouse 7.

Posted on February 25th, 2011 at 4:39pm.