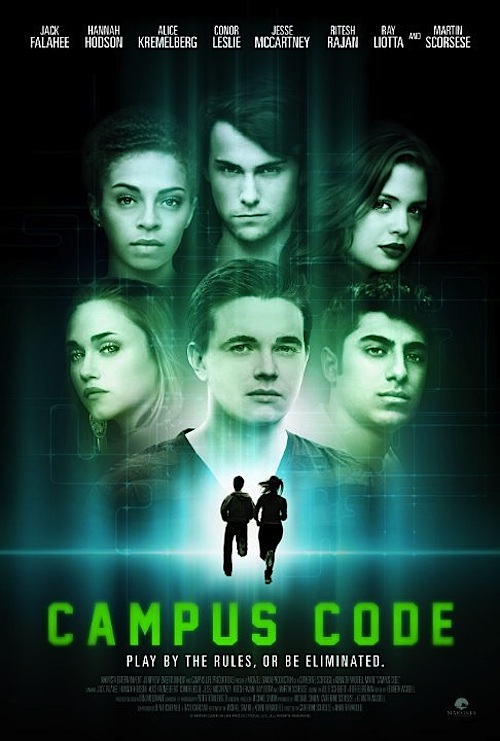

By Joe Bendel. If you thought campus speech codes were restrictive, try living by the mysterious rules and regulations governing this liberal arts college. It is never named, but it might as be Matrix U. Campus security is unusually fit and they respond to violations with suspicious swiftness in Cathy Scorsese & Kenneth M. Waddell’s Campus Code, which releases today on VOD from MarVista Entertainment.

Yes, Cathy Scorsese is the daughter of Martin, who pops up in a small role as the campus doctor, along with Ray Liotta who appears as the responsible bartender. This is not Goodfellas 2, though. In fact, Campus Code (or Campus Life, as it was once known) was briefly rather notorious for the bizarre litigation it spawned. Still, Campus is strange enough to be considered on its own weird merits.

Regardless, Scorsese’s doctor does not inspire much confidence. Fortunately, Ari seems to be okay without his services. In the first twenty minutes, he will fall from a thirteen story building and have a large pane of glass impaled in his head, without suffering any adverse effects. Of course, it still rather alarms Becca, the Good Samaritan, who drags Ari down to the infirmary for Scorsese’s close-up. He sort of returns the favor by saving her from the creepy Elliot.

Ari already had a bone to pick with the preppy perv, for bootlegging the original t-shirts designed by his partner Arun. Everyone digs Arun’s art, but nobody more so than the desperately smitten Izzy. Arun is also into Izzy, but he has a secret in his closet preventing him from fully committing. She too has a deep dark secret, which the goth rabble rousing Griefers are holding over her. They are demanding her support for some sort of self-governing petition that never makes much sense, even when the big reveals start coming fast and furious. Into the mix comes Greta, a cool transfer student, who sets out to falsely befriend Izzy, in order to put the moves on Arun.

Ari already had a bone to pick with the preppy perv, for bootlegging the original t-shirts designed by his partner Arun. Everyone digs Arun’s art, but nobody more so than the desperately smitten Izzy. Arun is also into Izzy, but he has a secret in his closet preventing him from fully committing. She too has a deep dark secret, which the goth rabble rousing Griefers are holding over her. They are demanding her support for some sort of self-governing petition that never makes much sense, even when the big reveals start coming fast and furious. Into the mix comes Greta, a cool transfer student, who sets out to falsely befriend Izzy, in order to put the moves on Arun.

For some reason, these six students are somehow suddenly exempt from the laws of reality, while the rest of the student body appears blissfully unaware of all the disturbing madness exploding around them. There will be sufficient answers to explain who and what everyone really is. Some of it is even rather clever. The problem is that Waddell and Michael Simon’s screenplay never establishes a baseline for reality, before upending it. Nor do they flesh out any characters before throwing them into the Matrix-esque maelstrom. Granted, they certainly do not waste any time on dry exposition, but it is hard to bring out the respective personas amid all the reality-problematizing noise.

Still, Hannah Hodson and Jesse McCartney are undeniably charismatic as Becca and Ari. They also benefit from their characters’ tougher, hipper attitudes. In contrast, Alice Kremelberg and Ritesh Rajan sort of blend into the background as the more passive Izzy and Arun. However, this is not a problem for Conor Leslie’s Greta, who turns out to be an engagingly forceful pseudo-femme fatale.

Code more-or-less makes sense when it is all said and done, but there are bushels of loose ends lying about. You have to wonder if considerable explanatory matter was cut for budgetary reasons. Yet, the legitimately twentysomething-looking cast is energetic to mostly sell the madness in the moment. It is all sort of grubbily entertaining for those who dig head tripping sf concept films. Recommended accordingly for the indulgent genre fan, Campus Code releases today (9/22) on VOD platforms like VUDU and iTunes, from MarVista Entertainment.

LFM GRADE: C+

Posted on September 23rd, 2015 at 11:34pm.