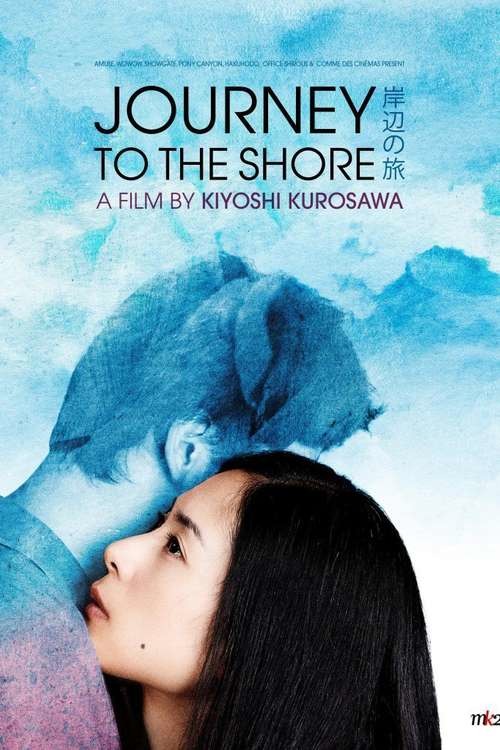

By Joe Bendel. Mizuki and Yusuke never actually use the “g” word. It carries too much baggage. After all, Yusuke still has physical form. He can walk around during daylight hours and be seen by others. It just so happens that Yusuke drowned three years ago. However, there are still rules to his current state of being, but Mizuki will accept them as best she can, to reacquaint herself with her dead husband in Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Journey to the Shore, which screens during the 53rd New York Film Festival.

Since Yusuke’s body was never recovered, Mizuki never had the closure she needs. However, when Yusuke suddenly appears, she sees it as an opportunity to renew their relationship. In a situation like that, you might as well be optimistic. Rather than fall into their old rut, Yusuke convinces her to take a road trip with him, visiting all the good decent people with whom he spent considerable time as he worked his way back to Tokyo from the coastal scene of his demise.

Most of them will be living, but some are also spirits, like Shimakage, the provincial newspaper distributor, whose persistent guilt for mistreating his wife keeps him tethered to the terrestrial world. It is all very instructive for Mikuzi, especially when she learns Yusuke worked as a cook in the traditional take-out restaurant owned by the very much alive Jinnai and Fujie. Yet, the latter is also profoundly haunted by mistakes from the past. Unfortunately, as they travel on, Mikuzi will start to understand their extra time together is probably not sustainable when she meets a similar couple suffering from supernaturally and stress-induced forms of mental instability.

Most of them will be living, but some are also spirits, like Shimakage, the provincial newspaper distributor, whose persistent guilt for mistreating his wife keeps him tethered to the terrestrial world. It is all very instructive for Mikuzi, especially when she learns Yusuke worked as a cook in the traditional take-out restaurant owned by the very much alive Jinnai and Fujie. Yet, the latter is also profoundly haunted by mistakes from the past. Unfortunately, as they travel on, Mikuzi will start to understand their extra time together is probably not sustainable when she meets a similar couple suffering from supernaturally and stress-induced forms of mental instability.

Journey is an achingly delicate, profoundly humanistic film that will choke you up several times over. It is all about forgiveness and acceptance, fully understanding there are no easy answers in life (or death). It is doomed to be compared to Kore-eda’s Afterlife, but with good reason. Both present an unfussy vision of the afterlife limbo, finding acutely human drama in such a metaphysically significant situation. They are both just great films that renew our faith in cinema without resorting to any special effects or gimmickry.

Although, strictly speaking, she is the one being haunted, Eri Fukatsu is absolutely haunting as Mizuki. It is a performance of quiet power and maturity, the likes of which we rarely see. She also develops believably complex and ambiguous chemistry with Tadanobu Asano’s Yusuke. However, her most emotionally devastating scene probably comes opposite Nozomi Muraoka as the guilt-ridden Fujie. (It is so overwhelming in its simplicity and honesty, it almost unbalances the narrative flow.)

Journey is a spiritually and psychologically intelligent film, featuring a terrific lead performance from Fukatsu and scores of accomplished supporting turns. Kurosawa never sets out to dazzle, but there are numerous scenes that sear themselves into memory. You could say it lives up to the unfulfilled promise of the disappointing screen adaptation of Matheson’s What Dreams May Come. Very highly recommended, Journey to the Shore screens Tuesday (9/29) at Alice Tully Hall and Thursday (10/1) at the Gilman Theater, as a Main Slate selection of the 2015 NYFF.

LFM GRADE: A

Posted on September 25th, 2015 at 2:24pm.