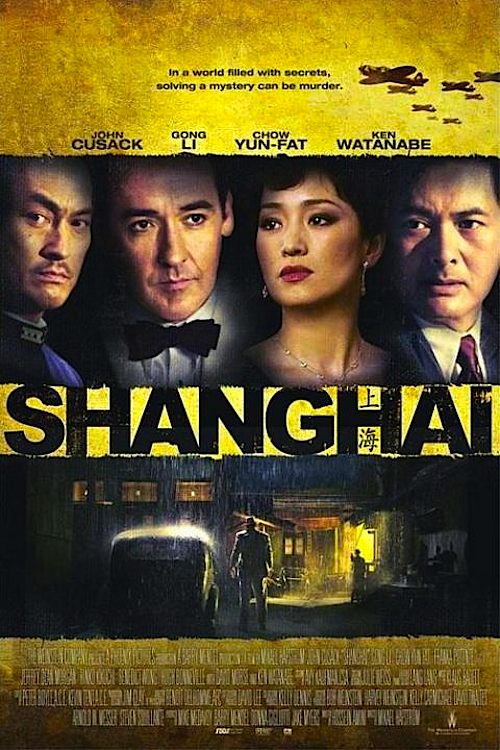

By Joe Bendel. We tend to forget Japan fought with the Allies in WWI. Afterward, British and American interests were just as determined to exploit the Foreign Concession system as their Japanese counterparts. Yet, Shanghai’s complicated and contradictory multinational governance made it one of only two completely open safe harbors for Jewish refugees during the so-called “Solitary Island” period. Obviously, the city is the perfect place to conduct espionage. Unfortunately, one of America’s best agents has just been murdered, but his friend and colleague intends is out to find the killer and make him pay in Mikael Håfström’s Shanghai, which opens this Friday in select theaters.

Paul Soames has assumed the cover of a National Socialist-sympathizing journalist, but he is really a democracy and freedom loving Naval Intelligence officer. However, his friend Conner was the true idealist. Yet, his prescient warnings about National Socialist and Imperial Japanese aggression were routinely ignored. Soames soon deduces Conner seduced Sumiko, the opium-addicted mistress of Tanaka, the police captain of the Japanese Concession and more importantly the local intelligence chief. Now suspiciously missing, Tanaka is turning the city inside out looking for her.

Soames’ search for Sumiko brings him into the orbit of gentleman gangster Anthony Lan-Ting and his society wife Anna. Lan-Ting has accepted an alliance with the Japanese for the sake of business, but his wife has secretly risen through the ranks of the resistance. Soames ingratiates himself with both Lan-Tings when he saves Anthony from an attack on Japanese officers organized by his wife, but executed without the surgical precision she had expected. She genuinely loves Lan-Ting, but like the wife of the local German military contractor, she finds Soames jolly fun to flirt with. Yet, as Tanaka cranks up the pressure, the attraction shared by her and Soames becomes more seriously ambiguous.

If you watch Shanghai soon after Zhang Yimou’s Coming Home, you will be astonished by Gong Li’s range. While she just rips viewers’ hearts out as the achingly tragic mother in Zhang’s literary masterwork, she plays Håfström’s noir heroine with all the va-va-voom you could ever hope for. She makes the screen smolder, even opposite a little twerp like John Cusack. Yet, she also compellingly projects the inner turmoil of a woman whose loyalties are divided between her husband and her country. It is a big, juicy, psychologically complex role, but Gong has the skills to pull it off.

Cusack just is not right for a Rick Blaine-ish romantic role, but fortunately, his gee whiz, fish-out-of-water persona works well enough for most of his solo scenes navigating the various intrigues. Jeffrey Dean Morgan plays Conner with characteristic intensity in his flashbacks (too bad he wasn’t the one paired up with Gong), but the ever-reliable David Morse is grossly under-employed as Soames’ embassy contact.

Cusack just is not right for a Rick Blaine-ish romantic role, but fortunately, his gee whiz, fish-out-of-water persona works well enough for most of his solo scenes navigating the various intrigues. Jeffrey Dean Morgan plays Conner with characteristic intensity in his flashbacks (too bad he wasn’t the one paired up with Gong), but the ever-reliable David Morse is grossly under-employed as Soames’ embassy contact.

Of course, Gong owns the film, but Ken Watanabe basically walks away with every scene she is not in. He is hardly another Captain Renault, but he is no Maj. Strasser either. Watanabe rather keeps us guessing, humanizing Tanaka, while playing his extremes to the hilt. Strangely, Chow Yun-fat is the one most conspicuously short-changed for screen time, but you can rectify that by watching The Last Tycoon, a natural companion film that focuses on a similar gangster-turned reluctant patriot. Unfortunately, Rinko Kikuchi is just squandered as the seldom seen Sumiko.

Attentive eyes will also spot future-star-in-the-making Andy On as one of Anna Lan-Ting’s comrades-in-arms. His appearances are brief, but his screen presence and action chops still come through loud-and-clear. Also look for Benedict Wong, who is quite good in the small but significant role of Juso Kita, Soames’ informer.

Håfström shifts gears from big historical set pieces to noir intimacy relatively adroitly. Hossein Amini’s screenplay intelligently incorporates the circumstances of the Foreign Concessions, as well as the events leading up to Pearl Harbor. Although he is clearly riffing on Casablanca, he wisely avoids paralleling the Bogart classic beat-for-beat. As a result, it all works quite well, in a pleasingly old fashioned kind of way.

Frankly, it is rather baffling why Shanghai’s release has been so long-deferred. In the intervening time, On’s star has risen, but Cusack’s has fallen, yet Gong remains on top of her game. She is more than enough reason to see Shanghai, along with Julie Weiss’s elegant costuming, Watanabe’s slyly villainous turn, and an unusual deep and accomplished supporting cast (blink and you miss Downton’s Hugh Bonneville). Recommended for fans of historical espionage thrillers, Shanghai opens this Friday (10/2) in key markets.

LFM GRADE: B+

Posted on September 29th, 2015 at 9:19pm.