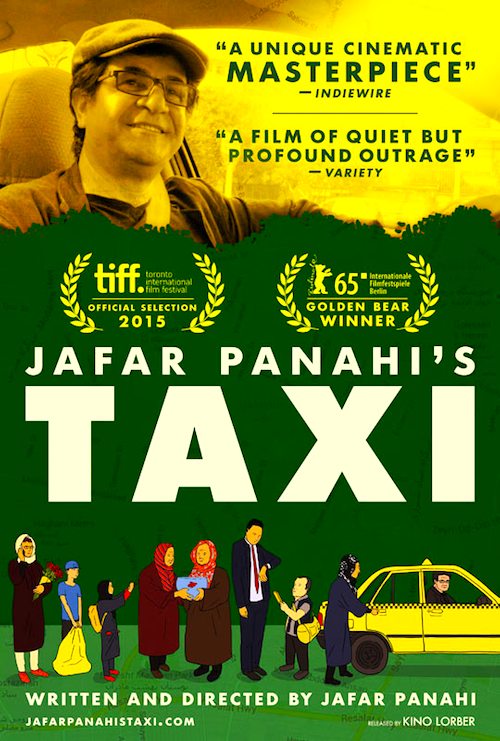

By Joe Bendel. Dissident filmmaker Jafar Panahi sort of brought the Taxicab Confessions concept to Iran, but most of the sins that need atoning are those of the Islamist government. The idea of Panahi working as a cabbie might sound appalling, but it makes sense as a cover for his defiant underground filmmaking. Cabs are a common sight on the streets of Tehran and they also have the advantage of being a moving target. Frankly, nobody is really sure how scripted it is, but each fare he picks up is significant in Jafar Panahi’s Taxi, which opens this Friday in New York at the IFC Center.

As the third film Panahi has made since being banned from filmmaking, Taxi is quite an accomplishment just for existing. Although his post-ban films are very self-referential by necessity, Panahi has yet to repeat himself. In this case, he appears to be making a hidden camera documentary about the average citizens who hail his cab, but some of the dialogue is so on the nose calling out his situation and echoing his previous films, it sounds suspiciously hybridized. Of course, on a more general level, the film itself can easily be interpreted as an homage to Abbas Kiarostami’s dash-cam taxi drama, Ten.

Some of Panahi’s “fares” recognize him, while some do not, but they all have something to say. His first two unrelated fares (picking up multiple hails is a standard practice in Tehran) argue about Sharia Law. She is appalled by the public executions, but he seems to think they serve a constructive role controlling society. His job? Mugger.

The third ride-sharer avoids political arguments, eventually revealing himself to be a bootleg hawker. Even Panahi has used his services in the past, because how else would he see Once Upon a Time in Anatolia? He is eager to sell the taxi-driving auteur on a sleazy “Panahi Recommends” bootleg scheme, but the director will not bite. We take it Panahi met plenty would-be exploiters of his ilk during his periods of house arrest. However, things start to really get serious when Panahi is flagged by an accident victim and his wife. During the brief trip to the hospital, they desperately try to hash out some sort of legal arrangement that would not leave her destitute should he die, since Iranian wives do not have inheritance rights under law.

In This is Not a Film, Panahi’s docu-essay capturing the frustration of his time serving the house arrest sentence, he was somewhat upstaged by his pet iguana Igy. However, he never stands a chance once his niece Hana steps in the cab. She has natural comic timing and a flair for delivering dialogue with a mischievous twist. If her scenes were extemporized then Heaven help her parents. Obviously, Panahi thinks she is the bee’s knees, even when she is delivering the heaviest commentary of the film. As part of a class assignment she is tasked with filming a “distributable” film. However, her teacher has given her a long list of absurd restrictions. Panahi knows them well.

In This is Not a Film, Panahi’s docu-essay capturing the frustration of his time serving the house arrest sentence, he was somewhat upstaged by his pet iguana Igy. However, he never stands a chance once his niece Hana steps in the cab. She has natural comic timing and a flair for delivering dialogue with a mischievous twist. If her scenes were extemporized then Heaven help her parents. Obviously, Panahi thinks she is the bee’s knees, even when she is delivering the heaviest commentary of the film. As part of a class assignment she is tasked with filming a “distributable” film. However, her teacher has given her a long list of absurd restrictions. Panahi knows them well.

Moments like that risk coming across as rather didactic, but Panahi maintains a street-level vitality that makes everything sound fresh and realistic. Beyond Hana, the movie-star in the making, his entire cast of “participants” always keep the film down-to-earth and the energy level cranked up. It would be nice to associate names with our praise, but they remain deliberately unidentified, for their protection.

As one would expect, the reality of Panahi’s situation is reflected in every minute of Taxi, by the secretive nature of its production. Still, he does not force his points, preferring to tease out a critique of current Iranian government and society over time. It is a clever and engaging film that would screen well in dialogue with Sanaz Azari’s criminally under-programmed I for Iran. Frustrating in its honesty, yet strangely satisfying for its resiliency, Jafar Panahi’s Taxi is very highly recommended for everyone who values free expression when it opens this Friday (10/2) at the IFC Center.

LFM GRADE: A

Posted on October 2nd, 2015 at 3:11pm.