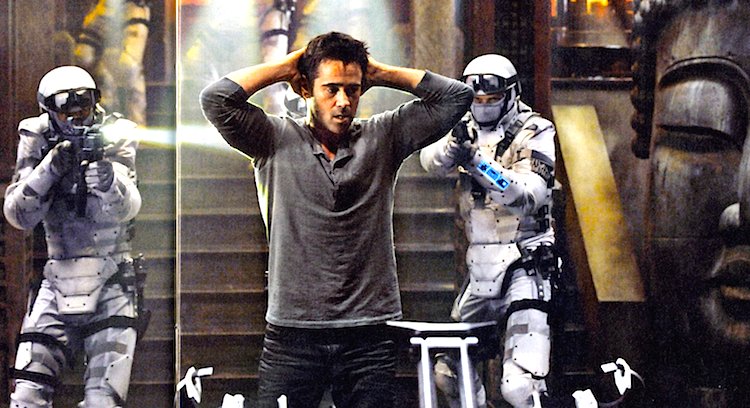

By Patricia Ducey. Now that the trailer for the remake of Total Recall is out, I thought about Colin Farrell and the trajectory of his career – how the actor once more famous for his partying than his acting climbed his way back to blockbuster status again, now reprising Arnold Schwarzenegger’s iconic role. How did he get from Alexander to Quaid? [See Colin Farrell discuss the new Total Recall here.]

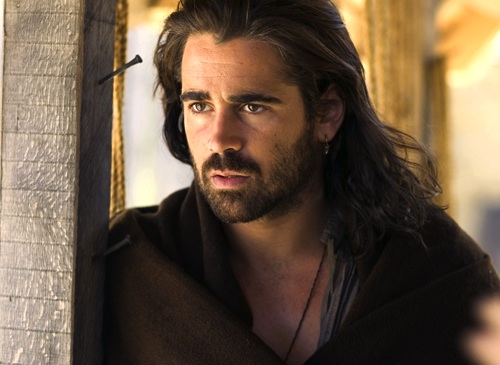

Farrell’s international career ignited when he, a Dublin native and actor in both Ireland and on the BBC, was cast by Joel Schumacher in Tigerland (2000) as Bozz, an edgy Texan army recruit. His smoldering good looks and credible Texas twang in the film made Hollywood sit up and take notice. With his Irish charm, his reputation for four letter words, and rebelliousness — plus his nudity in Tigerland — Farrell soon became known as much for his off-screen antics as for his roles, and for a while he was the enfant terrible of the film world. A blur of big roles followed Tigerland: he co-starred opposite Bruce Willis in Hart’s War, played Jesse James in American Outlaws, and worked with Steven Spielberg on Minority Report. He shot to the top of the acting world, and landed the cover of Vanity Fair — all before he was 25.

Then Farrell donned that platinum blond wig (but kept his Irish accent) for the title role in Oliver Stone’s unfortunate Alexander in 2004. Nominated for six Razzies, the movie was rejected by critics and moviegoers alike. He quickly went to work on a remake of Miami Vice, then collapsed at the wrap party and checked into rehab. Miami Vice collapsed, too.

Farrell had offended the lords of fame and cinema: his movies bombed, and his x–rated exploits felt, well, exploitative. He didn’t work much. And although many Hollywood notables who burn the flame at both ends never make it back (like Stone himself, still wandering in the desert after Alexander), Farrell did. In a series of small but memorable roles over the past five to six years, Farrell worked steadily and garnered attention for all the right reasons. By honing his affecting acting skills and leaving the bad-boy persona behind, he moved forward.

In four roles, especially — John Smith in The New World, Ray in In Bruges, Valka in The Way Back, and as Bobby Pellitt in Horrible Bosses — Farrell played against his good looks and roguish charm (and his much ballyhooed craic-loving ways) to create indelible characters instead.

When he read the script to In Bruges, for instance, he loved it. But he warned Martin McDonagh, the director, “I don’t think you should hire me. I come with a certain amount of baggage that has been well earned through the years and this piece is so pure, I would love the audience to not have too much of a relationship with any of the actors.” Luckily, McDonagh disagreed and hired him. The result is the character of Ray, a hit man who violates his own moral code by killing an innocent and who spends the rest of the film trying to expiate his guilt. Strangely, and thanks to Farrell’s portrayal, we root for him to do just that.

After Bruges Farrell played Valka, a Russian gangster in The Way Back (a film often written about here at Libertas, see here and here), another “minor” character with a believable, multifaceted identity. Valka admires toughness and demands it of others. With a tattoo of Stalin on his chest to honor one of Russia’s “tough men,” he eschews self-pity — “grateful is for dogs” — and doesn’t quit until he reaches the border. Turns out he is not so tough after all, though. At the border he realizes he can’t leave Russia, his beloved homeland – and as for freedom, he “wouldn’t know what to do with it.” Another deftly created character with just the right touch of saint and sinner.

On the comedic side, in Horrible Bosses Farrell undergoes a complete physical transformation as Bobby Pellitt, the obnoxious son of the boss. Vanity be damned, Farrell morphs into one of the most comically unlikable characters ever, yet the fierceness of Bobby’s lust for power (plus an almost heroically bad comb-over) earn our admiration.

But the first I saw of Farrell after his burnout was his role as Captain John Smith in Terrence Malick’s The New World. I was frankly surprised by the seriousness of his work – and his willingness to subsume himself into Malick’s ensemble – instead of dominating the screen. This was definitely not a star turn. In New World Farrell captures us without speaking — dialogue is always sparse in a Malick film — first as the rebel explorer, and then as Smith the man in love. I sought out Farrell’s films after that, and the string of memorable portrayals continued.

I’ve enjoyed him so much in these “supporting” roles that I almost hate to see him in the lead – of a blockbuster, no less – once again. Almost. By now he’s tucked the baggage away and earned his standing as a leading man. In the new trailer we can guess that his Total Recall is going to be different, with a vulnerability and emotional depth as evident as in his previous work. There’s a soul, not a cyborg, behind those eyes — and somehow I don’t think the stardust will blind him this time.

Posted on April 3rd, 2012 at 2:26pm.